Escaping Masculine Socialization and Generating a Transformative Vision

BY NYLA ALI KHAN

Do women’s multiple narratives reveal a capacity for alternative ways of negotiating the construction of conflictual identities? Does the assumption of agential roles by traditional women in a patriarchal culture cause an identity conflict crisis which can be resolved through a firm commitment to specific values and goals?

Do women’s multiple narratives reveal a capacity for alternative ways of negotiating the construction of conflictual identities? Does the assumption of agential roles by traditional women in a patriarchal culture cause an identity conflict crisis which can be resolved through a firm commitment to specific values and goals?

Women, as evidenced by the work of constructive and rehabilitative work undertaken by political and social women activists in the former princely state during both turbulent and peaceful times, have more or less power depending on their specific situation, and they can be relatively submissive in one situation and relatively assertive in another. Assessing women’s agency requires identifying and mapping power relations, the room to maneuver within each pigeonhole and the intransigence of boundaries [Hayward 1998: 29].

The history of Kashmir, similar to histories of other conflict zones, has never been sanitized. Also, although a class/caste hierarchy does not enjoy religious legitimacy in predominantly Muslim Kashmir, socioeconomic class and caste divisions in Kashmir are as well-entrenched as they are in other South Asian societies. A rigidly entrenched gender hierarchy also exists in Kashmir, although some substantive attempts have been made to deconstruct it. The role of women in a conflict zone; intersectionalities of class, education, ethnicity; religious identity in theorizing a woman’s identity; women’s agential roles or lack thereof are issues that can no longer be relegated to the background.

Inadequate attention has been paid to the gender dimension of the armed conflict in the Kashmir province of Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir [J&K], which stymies even further the emergence of peace, political liberty, socioeconomic reconstruction, and egalitarian democratization. As Dyan Mazura, Angela Raven-Roberts, Jane Parpart, and Sue Lautze [2005] observe:

inattention to, and subsequent miscalculations about, women’s and girl’s roles and experiences during particular conflicts and in early postconflict periods systematically undermines the efforts of peacekeeping and peace-building operations, civil society, and women’s organizations to establish conditions necessary for national and regional peace, justice, and security. [2]

Although women of Jammu and Kashmir have been greatly affected by the armed insurgency and counter insurgency in the region, they are largely absent in decision-making bodies at the local, regional, and national levels. As a Kashmir observer, I recognize the attention paid to gender-based violence in Kashmir by scholars, ethnographers, and NGOs, but not enough attention is given to the political, economic, and social fallout of the armed conflict for women.

I contend that not enough emphasis is laid on how Kashmiri women of different political, religious, ideological, and class orientations can become resource managers and advocates for other women in emergency and crisis situations. Kashmiri women continue to be near absent at the formal level.

Although the international community made a commitment to incorporate gender perspectives in peace efforts and underscored gender mainstreaming as a global strategy for the growth of gender equality in the Beijing Declaration and the Platform for Action in 1995 [Mazurana et al. 2005: 12], I observe that not enough is being done toward increasing women’s participation in peacekeeping and post-conflict peace building and nation-building in Kashmir.

Women’s organizations in a conflict zone like Kashmir need clear nation-building programs, which would involve reviving civil society, resuscitating the shattered economy, providing sources of income, and building social and political structures.

As in other conflict and post-conflict situations, women are rarely in positions of political power in participatory democracy. Although women are active in grassroots self-organization, they are seldom recognized for their work. It is important for these organizations to pave the way for sustainable peace, human rights and security which would diminish the potency of militarized peacekeeping, following closely on the heels of militarized interventions.

And militarized masculinities, even among peacemakers, as Sandra Whitworth points out, create “cultures of violence that may be perpetrated against women during conflict” [Feminism and International Studies: Towards a Political Economy of Gender in Interstate and Non-Governmental Organizations, 1994].

Cynthia Enloe [The Morning After: Sexual Politics at the End of the Cold War, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993] succinctly sums up the bolstering of militarization by gendered decisions: “When a community’s politicized sense of its own identity becomes so threaded through with pressures for its men to take up arms, for its women to loyally support brothers, husbands, sons, and lovers to become soldiers, it needs explaining. How were the pressures mounted? What does militarization mean for women’s and men’s relationships to each other? What happens when some women resist those pressures?” [250]

Dan Smith, director of the International Peace Research Institute, Oslo, makes a pertinent point about conservative gender politics [2001]. He observes that “people who make essentialist generalizations about women’s roles are usually unable not just to explain but even to acknowledge the diversity of women’s experiences and abilities.” [38] The espousal of essentialist politics does not allow for change that would enable “peaceful conflict resolution, reconciliation between traditional enemies, justice between different races and gender equality.” [46]

I observe that there is a serious lack of a feminist discourse in political/activist roles taken on by women in Kashmir, where the dominant perception still is that “politics and policy-making are linked to the powerful, strong, male realist rather than with the archetypal gentle, negotiating woman.” [Ibid.: 132] As in other political scenarios in South Asia, women politicians feminine traits, like reticence and a demure demeanor, cause them to be relegated to the “soft area” of Social Welfare. Although political parties in Kashmir, either mainstream or separatists, have not relinquished paternalistic attitudes toward women, women’s rights and gender issues are secondary to political power. Even within the domestic and feminized realm of home and family, women’s issues are peripheralized. In order to provide a more nuanced analysis of human security, it is important to access the everyday politics of work, state security, human security, war, displacement, compromise, and the way they are practiced on people’s bodies. In underlining the importance relational positionality to feminist politics, Daiva Stasiulis observes, “multiple relations of power interact in complex ways to to position individuals and collectivities in shifting and often contradictory locations within geopolitical spaces, historical narratives, and movement politics.”

The lack of consensus in India and Pakistan has been damaging to Kashmir. It is imperative that civil society actors and political actors work in collaboration with one another to focus on the rebuilding of a greatly polarized and fragmented social fabric to ensure the redress of inadequate political participation, insistence on accountability for human rights violations through transitional justice mechanisms, and resumption of access to basic social services. Otherwise the fate of women in Kashmir, as in some other conflict zones, is determined by humanitarian agencies and the international media that highlight their situations.

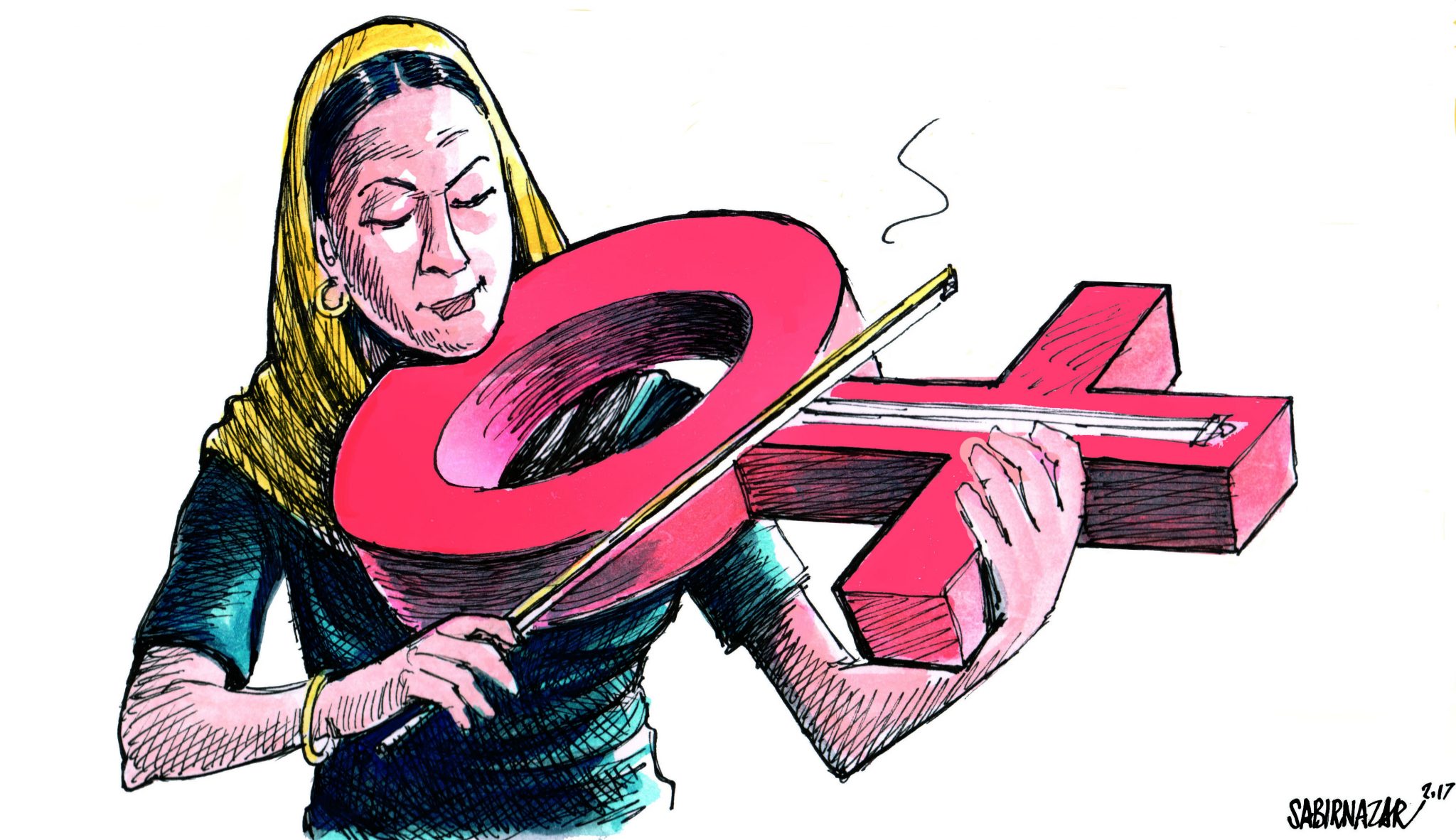

New efforts and new forums are required not just in Jammu and Kashmir but in other parts of the world as well for the germination of new ideas, broad based coalition politics that transcends organizational divides, and gives women the space and leeway to make important political decisions. In order to mitigate the conflict in Kashmir, “women have to re-establish their historic links with peace and the peace movement, asserting themselves as the harbingers of a genuine alternative. It is with this perspective in mind that women have to speak to those in public power and when they themselves are in public authority. This is very different from adopting, in the name of the search for equality, the existing masculinist and militaristic mentality” [Chenoy and Vanaik: 2001, 137].

In Northern Ireland, for example, prior to the peace moves between the paramilitary forces and the political institutions, women worked to forge connections across community, denominational, and ideological lines.

The most effective way to make a gender perspective viable in Kashmiri society would be for women, state as well as non-state actors, to pursue the task of not just incorporating and improving the positions of their organizations within civil society, but also by forging connections between their agendas and strategies for conflict resolution and reconstruction of society with the strategies and agendas of other sections of the populace impacted by the conflict. Women who urge their governments to initiate genuine peacekeeping, as Cynthia Cocjburn reminds us, believe that they can facilitate the process of rebuilding and peace “because they have escaped masculine socialization,” and are, therefore, “freer to formulate a transformative, nonviolent vision” [“A Gender Perspective on War and Peace”].

Nyla Ali Khan is the author of Fiction of Nationality in an Era of Transnationalism, Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir, The Life of a Kashmiri Woman, and the editor of The Parchment of Kashmir. Nyla Ali Khan has also served as a guest editor working on articles from the Jammu and Kashmir region for Oxford University Press [New York], helping to identify, commission, and review articles. She can be reached at nylakhan@aol.com.