BY MARION HILL

“It takes two to tango,” a trite statement but a true one.

That’s what I always think of when Republicans insist that a given piece of legislation must be “bipartisan.”

The problem is that the two parties don’t seem to have the same definition of “bipartisanship.” And frankly, when it comes to negotiations over issues, the Republicans have something to prove.

In order to have fruitful negotiations between two persons or two parties, both negotiators need to be able to trust the other. Both need to be “good-faith negotiators.” That means that, when each of the parties agrees during conversations about the issue that he/she will accept certain conditions provided the other accepts certain other conditions, each party should thereafter be able to trust that the other will follow through.

Typically, parties shake hands, nod affirmatively, or tell each other, “Yes,

that’s fine,” to indicate that each agrees.

Often a written contract follows an oral agreement, to make sure both parties have the same understanding about what was agreed to. But, in the olden days, when parties shook hands or otherwise agreed orally to a deal, that was it: the deal was made.

Even within the U.S. Congress, that was the way agreements happened years ago, back when legislators of both parties could be friends and could trust each other to do what they said they’d do. But that was the past. Today’s Republican party takes a very different approach.

Recall what happened when the Affordable Care Act [Obamacare] was being considered in Congress. For many months, President Barack Obama, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid negotiated with Republicans in Congress. Those Republicans made various demands for changes in the legislation in order to get their votes for passage, and changes were made – in order to get Republican votes as Republicans had promised. They had a deal. Or so Democrats thought.

In the view of many Democrats, those Republican-dictated alterations weakened the proposed health care plan and added unnecessary complexity. But in the interest of getting a “bipartisan deal,” they accepted the poorer provisions.

Then, what happened? Republicans reneged on their promise. Not a single Republican in either house of Congress voted for the ACA. It passed anyway. Speaker Pelosi is a real strategist and kept her unruly caucus together to provide the needed votes in the House. Majority Leader Reid, who notes that he spent eight years being “Obama’s quarterback” on the ACA, squeaked it by in the Senate with 58 Democrats and two Independents.

Need another, more recent, example of Republican untrustworthiness? When the House was considering establishing an independent 9/11-style commission to investigate the deadly Capitol riot of Jan. 6, Kevin McCarthy, leader of the House Republicans, empowered moderate Rep. John Katko of New York to cut a bipartisan deal with Democrats. McCarthy would bless the agreement, he said, as long as it included certain concessions he wanted about how the commission should be set up and should function.

McCarthy undoubtedly thought that Speaker Pelosi would never agree to all his demands and he could blame her for tanking the deal. But this was not Pelosi’s first rodeo. She realized McCarthy’s strategy and called his bluff, agreeing to almost everything Katko asked for. Katko reported back to his leader in triumph.

But then poor Katko was hung out to dry by McCarthy, who announced he would vote against the deal.

Some Republicans can’t even keep faith with other Republicans.

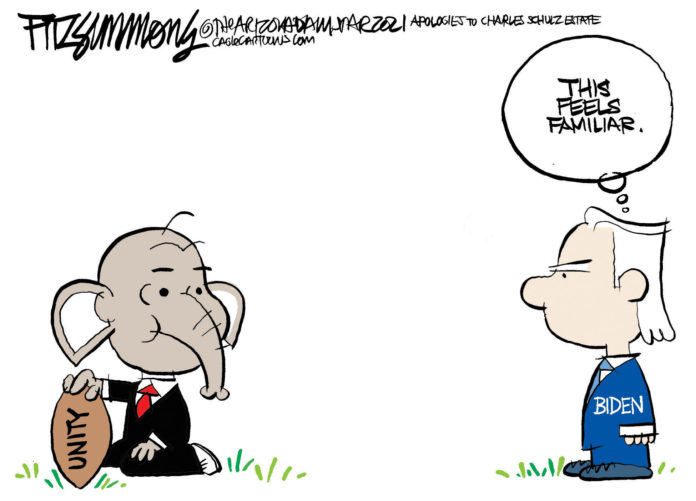

Democrats, like Republicans, are charged with governing. Unlike Republicans – or so it seems – Democrats want to actually govern. But they’re not Charlie Brown. One of these days, when Lucy Republican yanks away the football, there’ll be no Charlie Democrat falling over after trying to kick it.

And then, seeking bipartisanship will be shown to be a fool’s errand, merely a pipe dream from the past.

Durant resident Marion Hill is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. More of her essays can be found in Observer print editions.