BY MARION HILL

Articles about holidays, such as the Fourth of July, tend to sound about the same. Celebrating the Fourth each year, we recognize the nation’s gaining of independence from England and express thanks to all those who help the country remain free and independent. That includes, rightly, the men and women in the various branches of the military who give their time and expertise, sometimes even sacrifice their lives, in defense of the United States of America.

All that is as it should be. We must continue to remember the importance of our liberty and what is constantly required to maintain it.

But events sometimes force us to re-evaluate and develop the way we understand our democratic way of life and the preservation of it.

On Jan. 6, a mob broke into our Capitol in Washington, DC, the very seat of our country’s government. That attack highlighted how fragile our democracy actually is.

It’s possible we could lose it, but not to a foreign power as we’ve always perceived the threat. In fact, if not for the heroism of Capitol police officers, and that of others who work in that building, mob violence might have won that day. Our nation’s Capitol could have fallen to an invading force, something that hasn’t happened since the War of 1812, when British soldiers broke in and briefly held sway there.

The huge difference is that the invaders this time were our fellow Americans. And that’s not acceptable, no matter how unhappy some of our countrymen feel about actions by the government. We talk things out, we file petitions, we support candidates who’ll champion our views.

Yes, we sometimes march in the streets to call attention to a cause. But if a demonstration turns violent – if people are injured or property destroyed – that’s a black mark against the group and whatever purpose it was marching for. Such behavior loses supporters rather than winning more.

But in spite of the unwise and immature behavior of some on Jan. 6, I see encouraging signs that our country is moving toward a more mature view of itself and what it stands for.

Take the recent commemoration of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, for instance. That horrible event – in which a white mob attacked the peaceful all-black community of Greenwood [dubbed Black Wall Street by famed educator Booker T. Washington] and destroyed lives and property 100 years ago – was largely hushed up until very recently. But this year the anniversary was widely reported in both print and broadcast media, not only in the state but nationally.

And that tragic event was only one of many instances of previously hidden white-on-black violence in this nation’s past that were reported on in recent months.

Granted, this is a baby step. This country has much more reckoning to do with our racist history. But it’s a sign that at least we’re beginning to tell long-hidden truths and deal with them.

That much-needed reckoning won’t come easily, of course. Mention the words “critical race theory,” and you may start an argument.

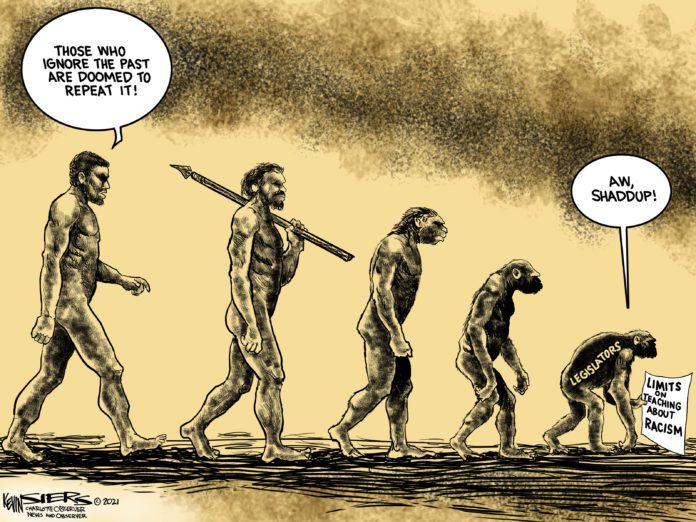

Critical race theory, or CRT, is the latest bugaboo of Republican legislators who want to control what can, and can’t, be taught in public schools. Oklahoma is one of five states that have already passed laws against teaching the concept, and more than 15 other states are considering such legislation.

But as a June 26 article by Maurice Mitchell in USA Today states: “Critical race theory isn’t taught at a single K-12 public school in the country.” Not one.

CRT is a concept that’s debated in law schools, where future lawyers rightly consider the backgrounds and applications of the country’s laws as they prepare to work in the country’s legal system. According to the website of the American Bar Association [www.americanbar.org], CRT “critiques how the social construction of race and institutionalized racism perpetuate a racial caste system that relegates people of color to the bottom tiers.”

Oklahoma’s anti-CRT law provides that lessons in public schools should not make an individual feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.”

News flash: Some elements of United States history should make us feel uncomfortable. And if our students are so fragile that they can’t stand to know the truth about our past, they will leave school poorly equipped to face any truths or to navigate their own future in this world.

Real education makes a student more knowledgeable about the past, not less. And the right to think and speak freely – even about this nation’s history – is at the core of why it’s so important to preserve our liberty.

That’s something worth fighting, even dying, for.

Durant resident Marion Hill is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. More of her essays can be found in Observer print editions.