BY ANN DAPICE

Pope Francis came to Canada last month. He offered apology for the Catholic Church’s role in Canada’s boarding school system, saying, “In the face of this deplorable evil, the church kneels before God and implores his forgiveness for the sins of her children.” Reflecting the conflicting emotions of the day, thousands applauded, some cried, for some the apology was not enough, for others it was a “start toward healing that would begin with forgiveness.” [Morrisseau, Indian Country Today, 7.26.22]

Pope Francis came to Canada last month. He offered apology for the Catholic Church’s role in Canada’s boarding school system, saying, “In the face of this deplorable evil, the church kneels before God and implores his forgiveness for the sins of her children.” Reflecting the conflicting emotions of the day, thousands applauded, some cried, for some the apology was not enough, for others it was a “start toward healing that would begin with forgiveness.” [Morrisseau, Indian Country Today, 7.26.22]

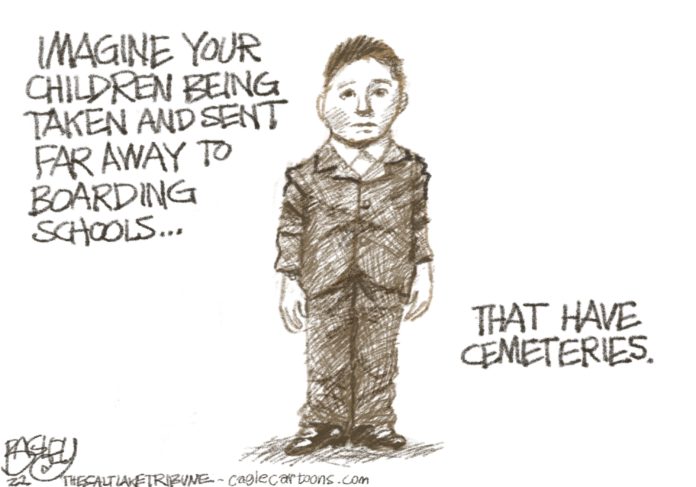

The recent discoveries of skeletal remains in Canada of 215 children in unmarked graves on the grounds of a church run school in British Columbia, followed by the finding of 751 remains on the site of a former school in Saskatchewan [New York Times] brought Indian Boarding Schools to people’s attention again. It is not news and the tragedy is not limited to Canada.

According to a UN report, indigenous boarding schools have existed in the U.S., Canada, Central and South America, the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, Scandinavia, the Russian Federation, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

And the abuse was not limited to Roman Catholic schools.

The residential schools began in the U.S. in 1860 and ended in 1978. There were 357 boarding schools in 30 states. Eighty-three percent of Indian children were in boarding schools by 1926. The schools were administered by Quakers, Methodists, American Baptists, Unitarians, Presbyterians, Mennonites, Southern Baptists, Roman Catholics, and the Reformed Church.

Preston McBride at Dartmouth College estimates that some 40,000 children died in or because of the schools. [Reuters]

In the U.S, and Canada, Native children were forcefully abducted by government agents, sent to schools hundreds of miles from home, beaten, starved and abused if caught speaking their languages. This was done as a response to what was said to be the “Indian problem.” The supposed goal was to “kill the Indian, save the man.” [Richard H. Pratt]

Through Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry [TMM] Oklahoma Indian leaders held the World Council of Churches Hearings on Racism against American Indians in Muscogee Nation offices in Okmulgee [1994]. We brought in people from across the U.S. They told their stories of boarding school horrors and deaths. Following that, TMM sponsored the committee on the UN-declared Decade of Indigenous Peoples [1995-2004]. We held programs and brought in speakers from across the U.S. every year of the decade. Some testified at the UN both in New York City and Geneva.

Some of our actions during this time included education of local religious leaders. In one such meeting, the mainline protestant minister following me on the panel said, “Yes, missionaries did terrible things but because of them I got Jesus!” It wasn’t clear why he as a White male wouldn’t have been able to “Get Jesus.” If disappointing to some, the Pope’s apology is of a higher order.

Along the way we would celebrate the life and work of the peace and justice activist, Congregational minister Russell Bennett. I first became acquainted with him when he helped us with the World Council of Churches hearings. After Indians traveled without reimbursement across the country to testify at the hearings, a summary of the hearings appeared in the World Council of Churches magazine, One World. Russell Bennett saw the article and called me in dismay. It said something to the effect that “Indians actually believe that they have been the recipients of genocide and while we know that not to be so, we feel compassion for them that they could actually believe this – even though we know that it is not true!”

And so began a thunderstorm. With Russell Bennett’s help, and the help of Sister Sylvia Schmidt of Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, we called the World Council of Churches in Geneva to protest. They were confused by our reaction. I received a phone call from Geneva while attending a wedding in Houston and was asked: “What do you want?” I replied, “Justice, Peace and Honesty.”

I reminded them that authorities estimate that the North American Indian population decreased from 12 million-18 million before European arrival to only 300,000-400,000 by 1900. Whole tribes became extinct [See Thornton, 1987; Stiffarm & Ryan, 1992; G. R. Campbell, pp. 67-108]. And because there were more deaths than births between 1492 and the end of the 19th century, a simple subtraction of numbers is not sufficient. Many times the remaining number actually died. [Thornton, pp. 42-43]

While a majority of American Indian deaths were the direct result of diseases to which they had no immunity, the deaths weren’t as innocent as has been portrayed – especially at universities. There can be no doubt that by this time in history people knew that removing food and shelter predisposed humans to disease and death! And “General Amherst, who approved of using whatever stratagem necessary to defeat the Indians, including germ warfare, wrote, ‘You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.’” [Weslager, p. 245]

There is endless documentation of the burning of Indian crops and villages, or what former University of Pennsylvania Professor Russell Thornton has called the scorched-earth policy. [pp. xv-xvi] Gen. Sheridan ordered the extermination of 60 million buffalo for the stated purpose of denying subsistence to the Plains Tribes.

In addition, tribes were constantly moved and forced on long “removals” with resulting illness and death. Large numbers were killed in massacres, and cash bounty was often posted for the delivery of “redskins.” Indians were killed for sport, which included the taking of testicles and vaginas for souvenirs. [Stannard, p. 144] There were 19th century written policies of complete extermination. [Thornton, 1987; Stiffarm and Ryan, 1992; G. R. Campbell, p. 75]

For these reasons, Indian mascots were also an important issue for Russell Bennett. Photos show his hand held up in solidarity with Indian people after testifying before a local school board affirming that the use of the term “Redskins” did not honor Indian people – but could only remind them of the many attempts to eradicate us.

And Indians were told their genocide was in their imaginations by an organization that was supposed to be examining genocide and racism. The World Council of Churches magazine, One World, did make a mild retraction and shortly thereafter stopped publication.

After a long fight against cancer, Russell Bennett called the day before he died talking about his memorial service. I’d told him we would honor the message of the Pendleton blanket given him in Indian ceremony a few years earlier. The name of the blanket was “Keep My Fires Burning” and I told him that it was our job to keep his fires burning.

There is more work to do. Russell Bennett left the model. Others can follow.

Ann Dapice [Lenape/Cherokee] received a PhD in psychology, sociology and philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania. She has taught and/or served as administrator at a number of universities teaching courses in the social sciences, philosophy and Native American Studies. She is Director of Education and Research for T.K. Wolf Inc., a 501(c)(3) American Indian organization and Founder/Executive Director, Institute of Values Inquiry. She received the Helen C. Bailey Award from the Graduate School of Education in 2013. Her cross-cultural and interdisciplinary research has been reported in professional journals, books, and academic presentations regionally, nationally and internationally – and in newspapers, radio, television, and the internet.