BY JOHN THOMPSON

During MAPS for Kids, one of the nation’s top education experts, the Chicago Consortium for School Research’s John Q. Easton, told us that no school improvement effort has ever worked without trusting relationships. This was the time, the 1990s, when test-driven, market-driven school reform began dismissing the social science and the traditional reform approaches which said that school improvement in high-poverty schools had to be a holistic process, addressing health, family, and community factors. The new reformers, who came to be known as “corporate school reformers,” countered that our children could not wait for progress in the war against poverty.

During MAPS for Kids, one of the nation’s top education experts, the Chicago Consortium for School Research’s John Q. Easton, told us that no school improvement effort has ever worked without trusting relationships. This was the time, the 1990s, when test-driven, market-driven school reform began dismissing the social science and the traditional reform approaches which said that school improvement in high-poverty schools had to be a holistic process, addressing health, family, and community factors. The new reformers, who came to be known as “corporate school reformers,” countered that our children could not wait for progress in the war against poverty.

These accountability-driven, competition-driven reformers borrowed the methods of venture capitalists, seeking a leverage point that would produce “disruptive” change. A new breed of venture philanthropists, the Billionaires Boys Club, replaced social science with Big Data, and billions of dollars were invested in the hypothesis that the answers to poverty and trauma could be found through rapid “transformational” changes in the classroom. They based their experiment on the hope that better instruction, curriculum, leadership, data, and accountability could close the achievement gap.

The gamble failed. Now, even the most committed believers in data-driven, choice-driven reform acknowledge that it was a mistake to discount the role of factors outside of school that are beyond the teachers’ control.

The biggest single experiment was an untested and hurried effort to “build a better teacher,” pushed by the Gates Foundation, and imposed across the nation by Arne Duncan, President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Education. Obama-loving educators like me had hoped that nearly a decade of failed reward and punish policies under No Child Left Behind would be repudiated, but Duncan filled his department with Gates functionaries. They, and other corporate reformers, doubled down on NCLB’s punitive characteristics.

Knowing that educators would resist the Gates-designed teacher quality campaign, they dismissed the concerns of researchers and practitioners, and used an untested, unreliable, and invalid statistical model as a stick for holding individual teachers accountable for rapidly raising test scores.

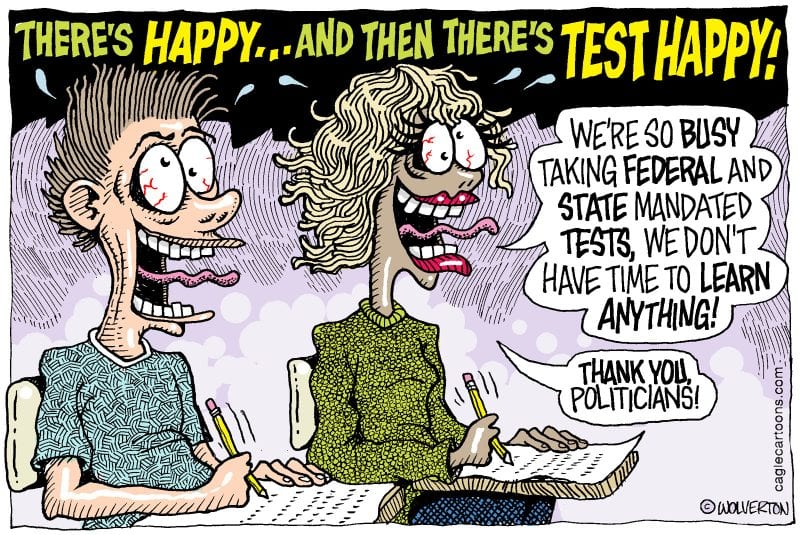

This rushed carrot and stick approach became law in Oklahoma and nearly 90% of the states. It used the stress of high stakes testing as the lever for overcoming the stress of poverty and trauma!?!? They used a dubious algorithm, which was biased against teachers in high-challenge schools, to attract the top teaching talent to those schools!?!?!

In conversation after conversation with Big Data experts, I was told that they believed that no more than 15% or so of teachers would see their evaluations unfairly lowered, and that was within an acceptable margin of error. They wouldn’t listen to educators’ responses: Why would teachers embrace a model where they had a 15% or greater chance per year of having their career damaged or destroyed by a statistical inaccuracy? Why would teachers not flee high-poverty schools when their evaluations are biased against educators in those schools? How could educators trust venture philanthropists who invested hundreds of millions of dollars in public relations campaigns that blamed us and our unions for failing to overcome poverty?

Moreover, Gates, Duncan, et al, heavily subsided dramatic charter school expansion that increased segregation, in order to reverse the legacies of segregation?!?! Worse, the battles between neighborhood schools and charters were measured by test scores, making teach-to-the-test a means of survival. As bubble-in accountability became dominant, and after the additional tens of billions of dollars for reforms were used up, budget cuts pushed teachers in many states over the edge.

Last year’s spontaneous teacher walkouts will soon be followed by two types of new strikes. Angered by both the way that top-down mandates drove the joy of teaching and learning out of many or most urban schools, and declining teacher salaries, walkouts are being organized across the nation. Worse, Los Angeles is about to see a strike provoked by venture philanthropists in order to pave the way for mass charterization of the school system.

The good news is that many testing and charter advocates acknowledge that they took too simplistic of an approach, and thus failed to improve student performance. I wish they would also admit to the severe damage done to many or most high-poverty schools by their experiment, but I don’t want to push that point too hard when communicating with Oklahoma reformers. I want us to call a truce, so we can get back to building trusting relationships.

I hope reformers will read a national journalist, Matt Barnum, who used to write for a fervent corporate reform entity, and who has been analyzing the lessons of school reform, while revealing hidden documents outlining the reformers’ plans for future battles. For instance, national reformers who funded a $175 million campaign to mass charterize urban schools have a once-secret plan to rebrand their attempt to “blow up,” or at least cripple, urban school districts, teachers unions, and traditional education schools. Its key component has been given the innocent sounding name of the “portfolio model.”

Locally, at least, educators face a dilemma. We should draw upon the lessons of education reform outlined by Barnum and others. His first lesson from 2018 research on what did and didn’t work is that poverty matters and must be addressed. Another clear lesson, ironically documented in part by research funded by the Gates Foundation, is that tougher evaluations didn’t work.

Barnum also stressed evidence that undermines the claims of voucher supporters. This year’s research further refutes the claim that money doesn’t matter and that retaining students [like Oklahoma does with the Reading Sufficiency Act] doesn’t harm kids.

The clear findings stressed by Barnum are win-win approaches, such as mentoring student-teachers [and students] and increasing learning time for struggling students. I would add that Oklahoma City had to abandon many of these constructive policies after the full corporate reform agenda became state law during the last decade.

And that brings me to experiences that help explain why education philanthropists should stop attacking educators who don’t agree with them, and why we should unite behind win-win policies. Over the last two decades, I have mostly had good experiences in communicating with local charter leaders, but not with national advocates for test-driven, charter-driven reforms. A top leader in the Obama Administration told me that I wouldn’t like the reason why he would be in Oklahoma, but that we should have drinks. As in previous discussions with him, we could make progress on all issues but one.

My friend repeatedly and adamantly refused to consider a reduction in the punitive side of policy. He claimed that we Democrats won’t have the credibility to improve schools until we prove themselves capable of punishing our own constituencies. In his job with one of the nation’s top billionaire reformers, he will continue to push charter expansion in Oklahoma, while defending the need for high stakes testing.

I hope local reform leaders will continue to listen to the research which explains how and why their policies failed in the ways that social scientists and educators predicted. I hope they will work with traditional advocates for funding holistic, positive, and proven interventions. But I hope they will understand why we won’t be able to build trusting relationships as long as the national advocates, who also help fund them, continue to rebrand and promote their anti-teacher policies.

Maybe something like this could be possible: Oklahoma charter leaders could thank their national donors for helping their charter schools. But they would unite and say that they will no longer remain silent as those venture philanthropists hurl falsehoods at fellow educators in traditional public schools. We could then build the trusting relationships that school improvement requires.

– John Thompson is an award-winning historian who became an inner-Oklahoma City teacher after the “Hoova” set of the Crips took over his neighborhood and he became attached to the kids in the drug houses. Now retired, he is the author of A Teacher’s Tale: Learning, Loving, and Listening to Our Kids.