BY GARY EDMONDSON

I have been wrong before:

- The Dave Clark Five did not permanently supplant The Beatles.

- Political platitudes are meaningless without follow-up actions.

- Some of the problems I worried most over were not even my to solve.

- My two months on the trombone have not shown the improvement I expected.

Twenty years ago, I wrote a column I titled “Huck Finn right for being wrong” in which I defended the teaching of Mark Twain’s novel in public schools despite the protests over the language Twain used.

As we drift through Banned Book Week, a corrective is appropriate.

“I was eloquent,” to quote Tom Hanks, in defending the constant slur against the slave Jim because the whole point of the novel was to show that Jim and Huck, at the lowest rungs of society, were the most moral people in that society:

“Someone looking for literature that endorses the bigotry of the times or an author’s prejudices can find such evidence in Shakespeare’s anti-Semitic The Merchant of Venice, Voltaire and Stendhal’s virulent attacks upon Roman Catholicism or even Zane Grey’s anti-Mormon tirade, Riders of the Purple Sage.

“In these books, the prejudices are presented at face value or endorsed by the author. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn refutes the racism by its very portrayal of the characters.

“We need to be reminded that actual, human-bondage slavery was the law in this country 135 [now 155] years ago. We need to be reminded that the entire ‘Southern heritage’ was constructed upon this rotten foundation. And we need to be reminded of how this corruption infected every aspect of society.

“That is the message of Huckleberry Finn. Criticize the book for being a heavy-handed polemic. Criticize the book for its weaknesses after Jim and Huck pass Cairo on their way down the Mississippi River.

“But to criticize the book itself as an example of racism show a woeful lacking of reading comprehension.”

All of that is still true, but that isn’t the issue. And I had overlooked my own evidence in my defense of total freedom of expression.

We don’t have to teach Huck Finn in our schools. The Celebrated Jumping Frog and The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg provide adequate introductions to Clemens. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is pretty even-handed in lampooning his own times and the Age of Chivalry. My favorite Clemens is Life on the Mississippi.

We choose some Canterbury Tales to teach and skip others. You can read most of Walt Whitman without encountering his homosexual love poems. You can read all of A.E. Housman with only the slightest hint of where his affections reside. We pick and choose the Shakespeare we include in textbooks.

One of my favorite poets, Robinson Jeffers, wrote many great short lyrics and some of the finest nature poetry ever penned. Is it censorship to teach those to students and not his violent, bloody, supposedly symbolic, often-incestuous narratives?

I cited other examples above, but we could insist upon teaching our youngsters the hilarious Roughing It, where Clemens bashes Mormons, or his even funnier Letters from Earth, where he slices and dices the entire Judaeo-Christian tradition.

Hmmm, seems as if that dreaded censorship is already shielding some students from embarrassment and in-class humiliation. Some, but not all. And that is the issue with Huck Finn.

The tradition of editors and others fiddling around with authors’ outputs dates to the beginning of written Western literature when some unknown someone distilled oral Homeric poems into standard versions of the Iliad and Odyssey.

Similarly, Charles and Mary Lamb cleaned up Shakespeare for kiddie consumption. Directors continue to prove their faux cleverness by mislocating the Bard’s plays in time and place. [Most were already period pieces.]

Thomas Jefferson cut and pasted his own version of the New Testament – as church leaders had earlier chosen what to include and exclude from the Biblical canon.

Aside from objections over any favorable depiction of any minority group, the most common argument raised against controversial books today is that they are “inappropriate” for the age group. [And as the first part of that sentence reveals, some folks’ emotional maturity is permanently stunted.]

Editing the classics, for whatever reason, has a long history. What should be remembered is that the value of the originals was not diminished. The Lambs’ Shakespeare is an OK introduction to the stories.

By high school, the originals should be understandable. By college, the subtleties and naughty bits can be explored. More people know the basic story of Romeo and Juliet than have studied it in depth.

Seldom before the third year of college do students get an in-depth look at any writer. Someone has always chosen what to make available in order to give students an idea about what writers stand for, how they put words together, whether further, independent reading might be worthwhile.

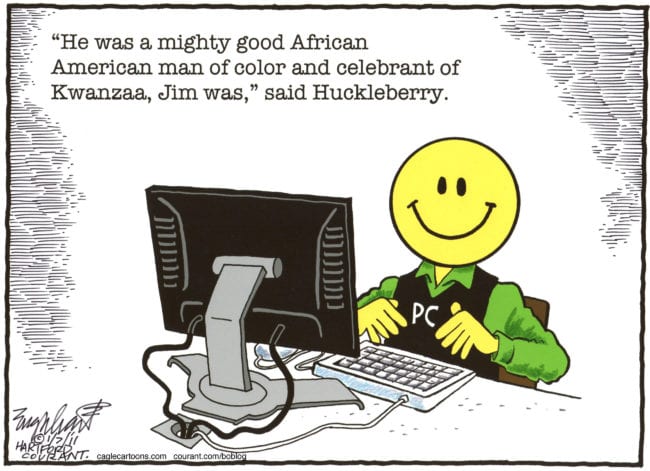

A sanitized Huck Finn could introduce young students to the story and its theme that the most despised among us – in this case, both Huck and Jim – often demonstrate more dignity and humanity than supposed pillars of communities. More mature students could investigate the themes further and develop a deeper understanding of the accepted atrocities of the time.

Cultures, as well as individuals, can mature.

I am 69 years old. I grew up – in Indiana – reciting the offensive version of “Eeny-meeny-miney-mo,” but have never considered teaching it to subsequent generations. One of the first books I read myself was Little Black Sambo [set in India], which I haven’t seen in bookstores for more than 50 years.

The television version of Amos ‘n’ Andy was a weekly staple in the ‘50s, but I expect to see it pop up on TV Land about the same time the Disney Channel airs Song of the South.

And topical satires have about the shortest shelf lives in literature before their time of relevance passes, before the conditions lampooned have changed enough that the satire becomes not a voice for change but a relic preserving the very conditions it criticized.

I have maintained for more than 40 years that while both sophisticated coasts were laughing at Archie Bunker’s ignorant bigotry, many racists saw it as a signal to re-emerge from their caves. The language and attitude was suddenly socially acceptable again.

I am sorry that we have not put our racist heritage behind us, but teaching it and reinforcing it should make everyone uncomfortable.