BY JOHN THOMPSON

Since I’ve retired from teaching high school in the inner city, I especially look forward to holidays for getting together with former colleagues. As we teachers meet each others’ partners, the ubiquitous question is “what do you do for a living?”

This Christmas, our introductions led to the question of how teachers should define ourselves. My answer, as always, brought silence.

We’re workers, I believe. We should stop worrying about being defined as professionals. I made a lot more money as a Teamsters truck driver and, as a teacher, I was often treated like a “worm,” which was my title as a rookie oilfield roughneck. I loved it, however, when my students called me “DT,” not Dr. Thompson.

A preacher replied that he shuns robes and other trappings and that the most honorific title he accepts is that of “pastor.” Preachers and teachers, fundamentally, are relationship builders and we don’t need the distraction of thinking about prestige and titles.

The next day on CSPAN, Politico’s Nicholas Carnes noted that the first question asked at cocktail parties is not, “what is your socio-economic status?” but “what do you do for a living?”

Carnes’ White Collar Government explains the crucial divide in Congress. It is a white-collar body. Fewer than 2% of congressmen have substantial experience as blue-collar workers.

Carnes shows that occupational history, more than any other factor, explains how politicians view economic issues. Lawmakers who have blue-collar experience hold more pro-worker beliefs and work measurably harder to advance the interests of the working class. His metrics show that they must work twice as hard to pass legislation in a Congress that is “out of step” with working peoples’ interests.

Carnes defines teachers as “service professionals,” as opposed to full-fledged professionals like doctors or lawyers. His research shows that teachers and social workers identify most strongly with workers.

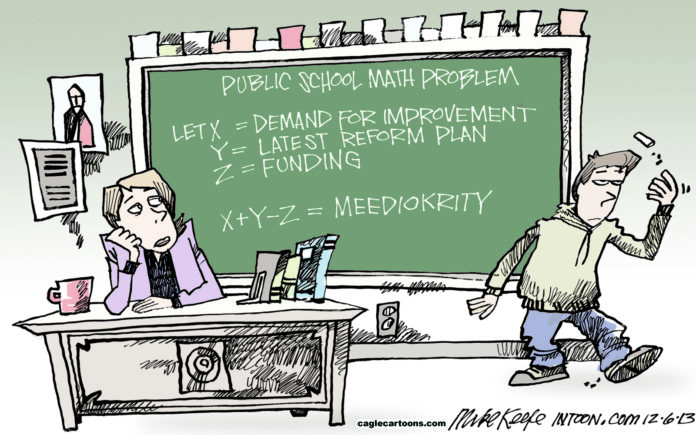

Carnes’ research should be read in tandem with Jal Mehta’s The Allure of Order. Mehta reviews the 20th Century’s three waves of standardized testing imposed by top-down reformers, as well as how and why they failed.

Mehta argues that data-driven reform has again mandated discredited policies because respected professions “colonize” less respected professions. Since teachers are just a “semi-profession,” outsiders feel entitled to micromanage us without paying attention to education research and history, or our professional judgments.

The way to break out of this destructive cycle, says Mehta, is to upgrade our standards and become a full-fledged and respected profession.

I quoted Mehta at this year’s Christmas party, but my fellow teachers were unimpressed. The BiIlionaires Boys Club has treated teachers and students as lab rats, and now their ill-conceived experiments are doing their damage.

In the three years since I left the classroom, the abuse piled on educators has grown far worse. My former colleagues were full of stories of the even nuttier policies that have been dumped on us.

By now, conservative and liberal educators, in this get-together and in other venues across Oklahoma, say that these idiotic mandates only make sense if the true purpose of reform is privatization of public schools.

I know my replies are unconvincing. I often sound like a peasant before the French Revolution: If the King knew what the aristocrats are doing to us, he would help us. If Bill Gates could be made to understand the harm he is doing …

I know that my continued efforts to work collaboratively with reformers are not promising – at least in the short run. I know that Carnes’ and Mehta’s research cast even more doubt on my approach of trying to communicate, human being to human being, with corporate reformers.

Carnes’ evidence argues against my hope that reformers are just “out of touch” with the world of teachers and poor students of color. There is no shortage of information about our world, he says. They just want something different than we do.

But, dang it, I see no alternative. Teaching is an act of love, not something that can be accurately measured. Teaching should be a team effort. “Professional” educators are no more worthy than bus drivers, lunchroom workers, and other mentors who help children grow into educated, healthy, responsible adults.

All too often we perform the services of social workers, mental health counselors, police officers, nurses, and paramedics. All of those duties require verbal acuity, book smarts, and hard-earned lessons from the school of hard knocks.

Our state’s motto is “Labor Conquers All.” Words, however, will not bring us respect. Perhaps, our actions can change the way that some of the elites behave, and maybe even feel, towards us. Regardless, with the poor and working people, we must take our stand.

I just can’t see personal or political benefits of trying to get the powerful to see us as professionals. The way we are viewed from above is a miner concern in comparison to the way so many other workers and children are treated. Why should we worry about the name given to our position in the team effort known as teaching and learning?

Those who preach, who coach, and who teach by sharing of themselves are teachers. Those who pass on lessons learned through the schools of hard knocks are teachers.

We are all workers who must join as equals in fighting for democratic and uplifting school cultures and humane workplaces.

– Dr. John Thompson, an education writer whose essays appear regularly at The Huffington Post, currently is working on a book about his experiences teaching for two decades in the inner city of OKC. He has a doctorate from Rutgers University and is the author of Closing the Frontier: Radical Responses in Oklahoma Politics.

“Teaching is an act of love, not something that can be accurately measured.” Does this statement imply a rejection of accountability? It seems that for many years the professional education establishment has fought, not promoted the “right kind” of accountability. Correct me if I have my facts wrong – in an age of budget stress, we can all be expected to have to prove our effectiveness.

Love is tough to measure, is teaching effectiveness more difficult to measure? Can no reasonable metrics ever be created to do this? Are we making “the perfect the enemy of the good”?

If both sides of this arguement cared, would not educators push for professional accountability (instead of leaving that open to politicians to impose) and would the tax-paying public happily pay professional wages to those who demonstrate performance? Until then charters will continue to erode the monopoly held on public education until the problem is fixed.