Douglass, KIPP Comparison Reveals Folly Of Reformers’ Achievement Theories

BY JOHN THOMPSON

From 2009-16, students attended two very different middle schools – the 97% low-income Douglass Middle School and 79% low-income KIPP Reach College Preparatory charter school, less than a mile from each other in Oklahoma City.

The neighborhood school, Douglass, had an Academic Performance Index [API] that was less than half of the charter’s [and its API was likely to have been inflated in a sad effort to meet No Child Left Behind targets.] KIPP served less than one-third as many special education students [and it didn’t have to deal with disabilities that were nearly as serious.]

Douglass has consistently received low “Fs” on state Report Cards, while KIPP received “A’s.” But how much of student learning is attributable to schools? We know that most learning is attributable to the socio-economic backgrounds of the parents, and about 10% to 15% is attributable to teachers, according to numerous studies. [see Hanushek et al. 1998; Rockoff 2003;Goldhaber et al. 1999; Rowan et al. 2002; Nye et al. 2004].

Stanford University’s Educational Opportunity Project, led by Sean Reardon, provides the best possible estimates of how much of student performance is produced by schools. Reardon, Ericka S. Weathers, Erin M. Fahle, Heewon Jang, and Demetra Kalogrides controlled for economic disadvantage and “analyzed 350 million test scores from 2009 to 2016, representing about 50 million students as they attended public schools from third to eighth grades. To compare apples to apples, scores from different state tests were converted to a single national yardstick.”

The Stanford study concludes that Douglass students scored 3.23 grade levels below the U.S. average, while KIPP students scored 1.85 grade levels above the national average. At first glance, it also appeared that KIPP did a better job of overcoming deficits due to poverty. Douglass scores were 1.2 grade levels lower than schools with similar free/reduced-price lunch percentage, while KIPP scores were 2.93 grade levels higher than schools with similar free/reduced-price lunch percentage.

But were those differences due to recruiting and retaining higher-performing kids who also had more family and social supports? How much “value” did the two schools add to student performance? Twice as many KIPP teachers were inexperienced; were they producing miracles or does the “No Excuses” model push out higher-challenge students?

During those years, Douglass students “improved by 0.14 grade levels [per year] more than schools with similar free/reduced-price lunch percentage.” KIPP scores “improved by 0.07 grade levels [per year] more than schools with similar free/reduced-price lunch percentage.”

For what it’s worth, Douglass was one of the lowest-performing schools in the neighborhood where three of the twenty schools ranked as the lowest-performing in the nation were located, and OKC’s KIPP has been seen as one of the nation’s top KIPP schools. So, what does it mean when Douglass student performance increases by twice the rate of OKC’s KIPP?

And that doesn’t include the learning that came from their participation in sports and other extracurricular activities that the charter didn’t offer.

When traditional [and usually useless] accountability metrics are combined with Reardon’s data, as well as other sources, such as ProPublica’s “Miseducation” database, KIPP’s tax records and data from the U.S. Office of Civil Rights, a fuller picture emerges.

KIPP spent up to $10,000 per student, which is around $1,400 more than Oklahoma City Public Schools [OKCPS] spent. That didn’t count its subsidized rent, or the savings it accrued by not providing transportation, sports, or support services for nearly as many high-challenge students.

During this period, KIPP’s four-year attrition rates for low-income and special education students were about 70%. And its extreme suspension rates for 2011-12 were documented by the Office of Civil Rights. KIPP’s suspended 41% of its students without disabilities once, while suspending 22.5% more than once. It suspended 74% of students with disabilities once. KIPP suspended 52% of disabled students more than once. That was nearly four times of the OKCPS’ multiple suspension rate.

By the way, the Stanford data does more than punch holes in the spin of supposedly “high performing” charters; it allows us to compare the outcomes of the more challenged OKCPS with those of the edu-philanthropists’ darling, the Tulsa Public School [TPS]. Edu-philanthropists bestowed millions of dollars of test-driven, choice-driven reform on the TPS. Tulsa’s outcomes indicate they would have been better off had they paid students to dig holes and bury the grant money.

OKCPS students scored 1.62 grade levels below the U.S. average. Its average scores were .68 grade levels lower than districts with similar socioeconomic status, but they improved at almost the same rate. Tulsa’s average scores were .81 grade levels lower than districts with similar socioeconomic status; its racial and economic achievement gaps were worse; and poor students declined further in comparison to districts with similar economic characteristics.

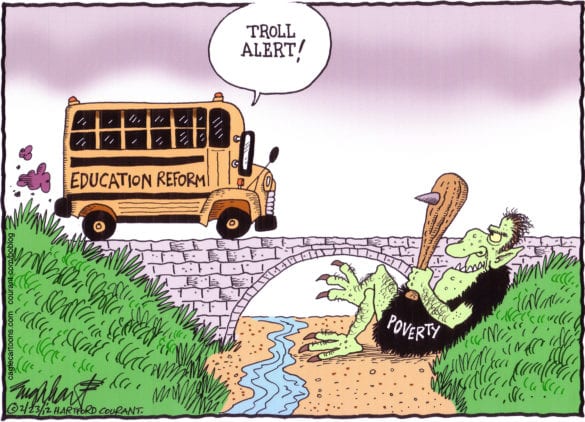

The Stanford data also provides a reality check in terms of the nation’s school improvement strategies. Corporate reform was propelled by the myth of “90 90 90” schools, schools that were supposedly 90% low-income, 90% minority, and in the top 10% in student achievement. This propaganda by rightwing and leftwing reformers convinced the “Billionaires Boys Club” and too many legislatures that “high expectations” and “No Excuses,” along with improved teacher quality, could close the Achievement Gap.

Partially because non-educators’ believed KIPP’s claim it serves the “same” students, corporate school reform was organized around a dubious theory.

They said, correctly, that poor children of color shouldn’t have to wait for society to address economic inequities and racial segregation. But these reformers hypothesized that data, accountability, and competition could rapidly produce shortcuts. They set out to social-engineer a “better teacher,” reward supposedly successful schools such as “No Excuses” charters, and micromanage and/or close failing schools like Douglass.

Reardon provides more evidence that the dominant school improvement model of the last generation was doomed to fail. He concludes that test score patterns are the result of “two phenomena – racial segregation and economic inequality – [that] are intertwined because students of color are concentrated in high-poverty schools.”

Moreover, “There’s a common argument these days that maybe we should stop worrying about segregation and just create high-quality schools everywhere,” said Reardon. Since he could not find a single district where the economic and racial achievement gap was closed, “This study shows that it doesn’t seem to be possible.”

Reardon couldn’t find a district whose outcomes support the idea that accountability-driven, competition-driven reform could close the achievement gap. But he participated in a study of 54 California schools where children of color performed better than the norm, and learned that “districts that have been able to find and keep fully prepared teachers,” and not rely on emergency certification, have lower achievement gaps.

We should heed Reardon’s finding, “It doesn’t seem that we have any knowledge about how to create high-quality schools at scale under conditions of concentrated poverty.” So … “And if we can’t do that, then we have to do something about segregation.”

The levels of economic and racial segregation we have in Oklahoma won’t be going away anytime soon. So, we need to reject the failed reforms that were imposed on our schools. Then we should respect the cognitive and social science which explains why shortcuts, such as the “teacher quality” fad and school closures, won’t work, and seek equity in the entire community, not just in school buildings.

It makes no sense to use the stress of testing and competition to overcome the stress of poverty and segregation. To provide equity, we must bring the full array of adults from our community into our schools, and bring our students out into the full diversity of Oklahoma City.

John Thompson is an award-winning historian who became an inner-Oklahoma City teacher after the “Hoova” set of the Crips took over his neighborhood and he became attached to the kids in the drug houses. Now retired, he is the author of A Teacher’s Tale: Learning, Loving, and Listening to Our Kids.

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the October 2019 print edition of The Oklahoma Observer.