BY RICHARD L. FRICKER

I knew Cody Young only in a peripheral way. He and my son were classmates and skateboard buds. My wife remembers he would come over for a homemade Orange Julius on hot summer days. Thus with great sadness we learned of his death May 21, in what Tulsa Police are calling a standoff.

I knew Cody Young only in a peripheral way. He and my son were classmates and skateboard buds. My wife remembers he would come over for a homemade Orange Julius on hot summer days. Thus with great sadness we learned of his death May 21, in what Tulsa Police are calling a standoff.

How did a young man, 22 years old, who once entertained being the next Tony Hawk become the target of a police kill shot? My son – and many of Cody’s other friends – recount him as non-violent with a big kind heart. What happened?

War! That’s part of the answer, but only part.

The Tulsa Police Department says they responded to reports of someone shooting at parked cars from a second floor apartment near 11th and Rockford Ave. about 1 a.m. Nothing in their release indicates Young fired specifically at officers or anyone else, only that he had a long gun at the window. Reports vary as to whether the weapon was a rifle or shotgun.

Unbeknownst to Cody, his friends or family, his life began to unravel just before graduation from Thomas A. Edison High School. It’s referred to as a Preparatory School; there was no way it could have prepared Cody for his future.

Young men are prone to see themselves as immortal, impervious to injury and death. This immortality is joined at the hip by desire for adventure, or just something different to get out of town. Cody joined the Oklahoma National Guard.

The Afghanistan and Iraq Wars were in full bloom. It would be naïve to think he didn’t know there was a good chance he would wind up in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Cody was nine when Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda attacked the New York City Trade Center and Pentagon. By 2011, it had been a decade since 9/11.

Cody had traded his skate board for weapons of war. He was now a soldier in the Oklahoma National Guard – the Thunderbirds whose motto “Always Ready, Always There” had deployed to Afghanistan.

The Oklahoma Thunderbirds has a proud combat tradition in many engagements in many wars. Of World War II they were said to be the first guard unit into Europe and last unit out.

Afghanistan would be different. As chronicled in Phillip O’Connor piece, The Deadliest Day, about a patrol on Sept. 9, 2011, “The firefight lasts maybe 15 seconds. When it is over, Oklahoma and its 7,500-member Army National Guard are left to face the state’s bloodiest day in combat since Korea. Three soldiers are dead and two seriously wounded.”

Before Cody and the Thunderbirds returned home 14 men died and scores were injured. Many Thunderbirds had been in combat, others had not. One soldier cited by O’Connor affirmed what anyone who has been to war knows: “Everybody wants to see combat, until they see it.”

Cody, like the others of his deployment saw a lot. According to family and friends Cody returned changed, he was distant. He told his mother “something was wrong.”

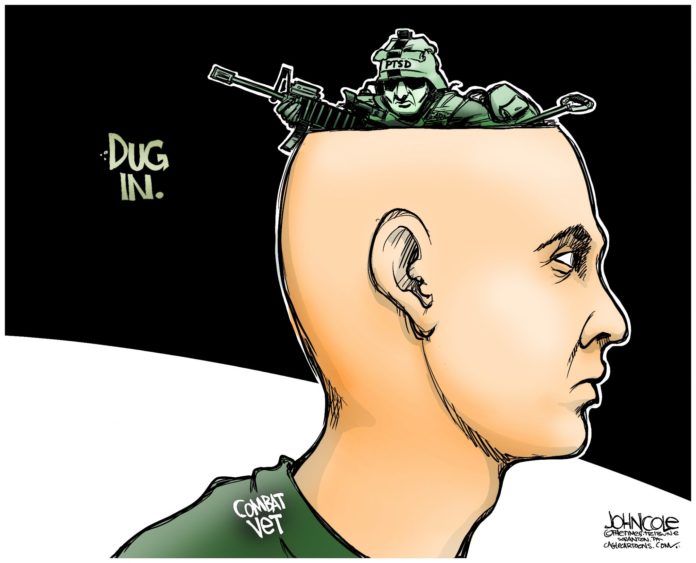

That something was Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome [PTSD].

PTSD is a war disease. The symptoms vary; flashbacks, disassociation, depression often self-medicated with drugs or alcohol, and most and worst of all, nightmares and flashbacks.

The flashback is: You are in the present and the past simultaneously, unsure which is real. You’re not sure how you got to this moment; a song, an aroma, a sound, a conversation, a movie? Anything can trigger and you’re left with very little control.

You are in combat. Someone must guide you out or it continues until you wear out or pass out.

Nightmares arrive unannounced, until someone wakes you because they hear you screaming, or they run their course and you wake up shaken and confused. Then the long night begins, fighting sleep fearing the nightmare will return.

According to Cody’s mother, he had all the classic PTSD symptoms. He had sought help, but almost nothing was working.

Cody, according to reports, spent his last night watching a war movie with a friend. Then something happened.

Only Cody knows what triggered taking up a weapon and firing at parked cars out the window. Did Cody try to tell the assembled police responders? The police say he was “mumbling” something.

Police say they couldn’t understand what he was saying. Cody had being trying to say something since he returned from Afghanistan.

At some point, according to TPD accounts, he raised his weapon. Only Cody knows where he was or what he seeing. We do know there were a lot of police around. We do know they brought in one of their armored vehicles.

The TPD action was standard procedure. But, surrounded and confronted by an armored vehicle, did that procedure have any meaning to Cody, or was he in another reality?

Cody can’t tell us.

He was mumbling. Did anyone try to communicate with Cody?

Seventeen-year veteran officer Gene Hogan ended Cody’s life with a single rifle shot. Nine days earlier Hogan led the 5th annual Jared Shoemaker Memorial Walk.

Corporal Jared Shoemaker, a U.S. Marine and Tulsa police officer, killed during a deployment to Iraq in 2006.

To date it is not known if Hogan was given a kill order, or if TPD leaves that decision up to individual officers. Presumably, there will be some type of TPD after action report.

According to Stacy Bannerman, author of When The War Came Home: The Inside Story of Reservists and the Families They Leave Behind, writing for Truthout.org on May 26, “National Guardsmen have been found to have rates of PTSD as much as three times higher than active duty troops after combat.”

Continuing she says, “The vast differentials in mental health outcomes between reserve and active duty are primarily due to: the lack of post-deployment unit support; markedly poorer post-deployment mental health services and follow-up; and the rapidity with which citizen soldiers return to civilian life after combat.” Remarking on Cody’s death she said it was “not isolated.”

Locally, H. Caldwell “Callie” O’Keefe, VFW Post 577 Chaplin, U.S. Marine veteran of Vietnam, said, “The needs of these veterans is not being addressed by the VA, there needs to be a lot more therapy.”

Caldwell’s remarks echo concerns that military and VA doctors have been encouraged to downgrade PTSD findings to such things as “personality disorder.” Caldwell said, “If they call it personality disorder they [DOD and VA] don’t have to pay as much.”

In 2013 the Army completed a study of PTSD diagnoses at Madigan Army Medical Center which was prompted by discovery of a memo released by the Seattle Times quoting a center psychiatrist telling colleagues, a soldier who retires with a post-traumatic-stress-disorder diagnosis could eventually receive $1.5 million in government payments.

The memo claims, “He [the psychiatrist] stated that we have to be good stewards of the taxpayers’ dollars, and we have to ensure that we are just not ‘rubber stamping’ a soldier with the diagnoses of PTSD.” Such findings, it was claimed, could cause the Army and VA to go broke.

The Army has resisted media efforts to release the complete study.

“People,” Caldwell said, “who have seen combat are getting f—ed up. The public has no idea how prevalent PTSD is and if they did it would scare them to death, as if they’d had to go there themselves.”

The VA is under fire with calls for Veterans Affairs Secretary Eric Shinseki’s resignation. Sen. Richard Burr, R-NC, ranking Republican on the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, publicly chided veterans groups for not joining in asking for Shinseki’s resignation.

These groups wasted no time responding to the senator, calling his attack a “cheap shot,” among other things.

In the end, Cody Young was a young man who served his country with honor and in the process came home a walking casualty. In the end, it doesn’t matter if he were killed by Taliban or TPD, he will be missed by family and friends no matter who ended his life.

We must ask what Cody has taught us about sending our young into the meat grinder of war, understanding their needs and care when they return. The Codys are not data, they are not the things parades are made of to make society feel good when they die.

Looking back, it never occurred to me the skateboard kid with the Orange Julius would, in a few short years, become my brother in arms. That he and I would become veterans at about the same age in our lives.

I would have tried to know him better. But such are the fates.

Cody’s name will not be on a marble wall. Hopefully he will be remembered with those whom he served.

I like to think that somewhere in the dimensions of the cosmos, Cody is skating half-pipes with no memory of what brought him to that place.

In war we all become casualties. The Codys are among us and there will be more.

– Richard L. Fricker lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. His latest book, The Last Day of the War, is available at https://www.createspace.com/3804081 or at www.richardfricker.com.

E-mail: richardfricker@okobserver.org