BY SHARON MARTIN

I didn’t learn to swim as a child. After years of adult water aerobics, I came to realize that the water would hold me if I just quit fighting it. Helping fifth graders add and subtract mixed numbers this week, it came to me that this applies to math education as well.

I didn’t learn to swim as a child. After years of adult water aerobics, I came to realize that the water would hold me if I just quit fighting it. Helping fifth graders add and subtract mixed numbers this week, it came to me that this applies to math education as well.

Just as you have to understand the properties of water to swim, you have to know in your bones the properties of numbers to do math. If you cannot add, subtract, and multiply automatically, fractions and algebra are just so difficult.

Why do we race ahead in math instruction without making sure that students have this basic number sense?

My co-worker, Heather Neal, had an awakening this week, too. The first graders at our school were standing on their heads, both literally and figuratively, during the recent indoor-recess weather. What to do? She had them get out of their chairs to dance and sing their spelling words. Not only did the students have a lot of fun but they blew their spelling test scores out of the water.

Kids need to move.

Sometimes this inability to sit and learn isn’t due to the weather. One of my morning jobs is lunchroom duty. When the kids eat cinnamon rolls or have waffles [even whole wheat] in a pool of syrup, the second graders who come to my room first thing after breakfast can’t focus on much of anything. I love scrambled egg mornings and even sausage biscuit days.

What kids eat affects their behavior.

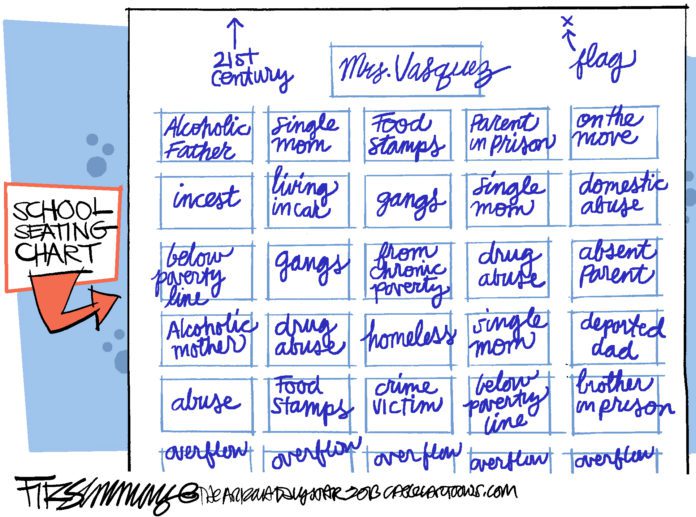

And what happens at home affects how a child learns. Even very young children can tell you all about video games, but few of them know nursery rhymes or fairy tales that haven’t been made into animated movies. Kids don’t have to give up all video games and television, but they must have an intimate relationship with books, stories, and conversation, and it must start early.

One study showed that a strong indicator of student success in school was whether or not a child had dinner at the table in the evening with family. This act builds relationships, teaches manners, increases vocabulary, and introduces the world of ideas.

My time in a reading classroom confirms this.

Another long-term study found that students who grew up in homes with at least 500 books were even more likely to attend [and graduate from] college than those whose mothers had college education.

Parents must be part of any school reform. They are the children’s first teachers.

Experience makes teachers classroom experts. We learn even as we teach. Ask us what we know. Then listen to our answers. This is where real reform must begin.

– Sharon Martin lives in Oilton, OK and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer