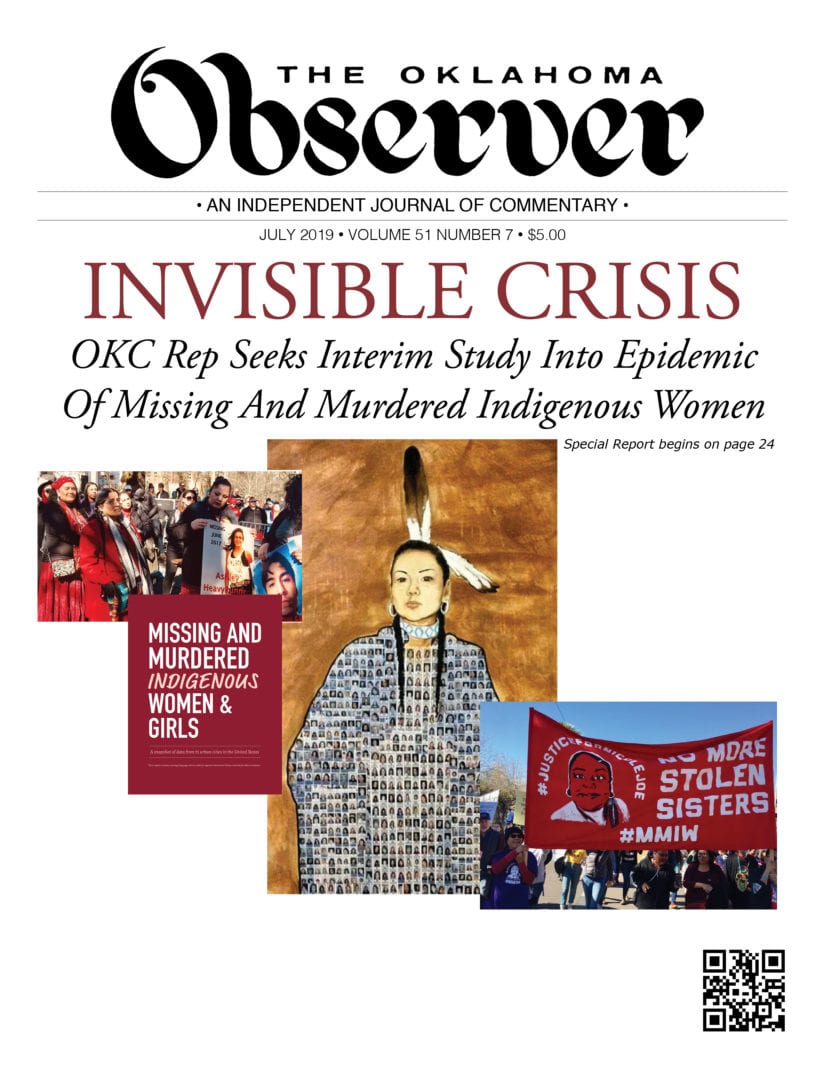

Whether living on tribal lands or in urban areas, native women and girls are murdered or disappear at alarming rates. Oklahoma is 10th in the number of such cases – many of which go unsolved. Lawmakers at the state Capitol and in DC finally are working to address the crisis.

BY ARNOLD HAMILTON

LaRenda Morgan and her family are living a nightmare. In June 2015, Morgan’s first cousin, Ida Joanne Beard, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne Arapahoe Tribes of Oklahoma, vanished without a trace at age 29.

“The [El Reno] police investigated, but didn’t have many leads,” said Morgan. “They didn’t do a very long investigation on it.”

For Native American women, Beard’s disappearance is an all too common fact of life, yet one law enforcement and policymakers – whether at the local, state or federal levels – are only beginning to come to grips with.

“It’s a crisis that’s been ignored for a long time,” said state Rep. Mickey Dollens, D-OKC. “It’s a shame it’s taken this long to acknowledge.”

Dollens wants to do something about it at the state level. He is seeking to conduct an interim legislative study aimed at finding ways to help state, local and federal authorities and tribes better quantify, understand and respond to the crisis.

His proposal is one of 145 filed earlier this month by House members wanting to conduct interim studies on a variety of topics. House Speaker Charles McCall, R-Atoka, will decide by July 19 which will proceed.

In Washington, meanwhile, Congress is weighing measures aimed at improving coordination between federal agencies and tribes and standardizing the Justice Department’s response to reports of missing and murdered native women.

Why native women are targeted disproportionately isn’t clear. But the statistics are staggering: Murder is the third leading cause of death among native females ages 10-24 and more than 5,700 American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls are listed as missing, according to recent National Crime Information Center data.

Moreover, the National Institute of Justice reports 84% of native women experience violence in their lifetime – 97% of which is perpetrated by non-natives. And the Seattle-based Urban Indian Health Institute has identified 506 cases of missing and murdered native women and girls since 2010 in 71 cities across the country.

Oklahoma is No. 10 nationally in the number of missing or murdered indigenous women, according to the UIHI report.

“There is a disconnect,” Dollens said, “between tribal police, states, the FBI, and municipal, and county law enforcement regarding how these cases should be handled.

“We want to look at the options on bringing everyone to the table to listen to the experiences of those who’ve advocated for years on behalf of missing and murdered native women. We want to give them a platform to be heard.”

Dollens believes the study could lead to a new statewide database that helps law enforcement across jurisdictions solve more of these cases.

Congress seems to have recognized the problem, too, no doubt prompted by the fact only 116 of the 5,700-plus cases of missing native women and girls made it into the Justice Department database, according to the National Crime Information Center.

“Sometimes the record of that missing indigenous woman or person isn’t documented, leaving questions unanswered for sometimes decades, leading to gaps in information, missing person cases unsolved and perpetrators roaming the streets,” said New Mexico Rep. Deb Haaland, one of the first two native women elected to Congress.

Both the House and Senate are working on versions of legislation – dubbed Savanna’s Act – that seeks to improve coordination between federal and tribal law enforcement and other agencies. It’s named for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a young pregnant woman was abducted and murdered two years ago in Fargo, ND.

Haaland is one of the principal authors of Savanna’s Act in the House. Three other Native American members of the House, including Oklahoma’s Tom Cole [Chickasaw] and Markwayne Mullin [Cherokee], are co-sponsors.

Cole and Mullin also are co-authors, along with Haaland, of the Not Invisible Act that would create an advisory committee to make recommendations to the Justice and Interior departments on how to address the crisis. The panel would consist of tribal leaders, law enforcement, victim’s families and survivors.

There is little doubt that jurisdictional hurdles can create headaches for law enforcement agencies investigating cases of missing and murdered native women.

But sadly, some cases involving Native American victims are not given as high a priority – whether because of race or misunderstandings of tribal sovereignty.

“This is a commonality with native women when this happens – not just in Oklahoma but across the nation,” Morgan said, noting too many cases simply are “not taken seriously” by law enforcement.

“It should be a no-brainer. If it were to happen to any other nationality or race, it would be investigated. All cases should be treated the same.”

In Beard’s case, the family hired a private investigator. It also reached out to media, hoping someone would tell her story. None did. The case remains unsolved.

“I know we’re not the only family this has happened to,” Morgan said, “but it’s like – wow! – is it because we’re native?”

Approving Dollens’ proposal should be an easy call for the House speaker. Oklahoma could wait, of course, for Congress to act. But this is a crisis that demands all hands on deck – including those at NE 23rdand Lincoln Blvd.

“If anything,” Dollens said, “one of the goals of the study is to gain clarification on whose jurisdiction it is – federal, county, state, local, tribal.

“We want to create collaboration with the native community and help any way we can to solve these crimes and find missing people.”

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the July 2019 print edition of The Oklahoma Observer.