First In A Series

BY DON McCORKELL

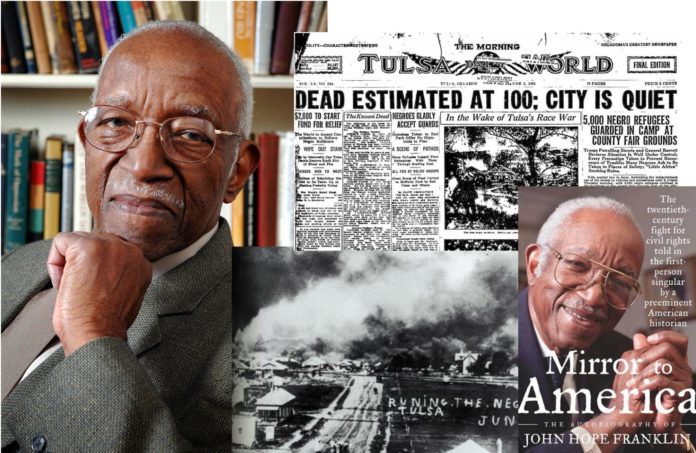

Legacies tend to fade away with time, but there are exceptions, individuals whose singular impact was so vivid and so vast that the passage of time only sharpens their image. This year is the 100th anniversary of the birth of John Hope Franklin, and he was one of those rare individuals who was able to light fires for justice far beyond his personal reach.

There are probably only two historians from Oklahoma who have had a profound impact beyond their own time. Angie Debo, who documented the vast and searing mistreatment of Native Americans in her majestic Still the Waters Run, was one. John Hope Franklin, whose monumental examination of the history of African Americans, was the other.

Franklin was born in Rentiesville in eastern Oklahoma and grew up there and in Tulsa where he graduated from Booker T. Washington High School. His father, Buck, grew up in Indian Territory, starting as a rancher and then turning to law, moving his law practice from Rentiesville to Tulsa in the early years of the 20th Century.

Franklin and his mother and sisters remained in Rentiesville waiting for the time they could move to Tulsa, which to them sounded like the Promised Land. They did get to make that move, but only after the horrendous Tulsa race riot in which the black community was devastated and Buck’s law office burned to the ground.

The city doubled down on its racist acts by passing an ordinance to prevent blacks from rebuilding. Franklin’s father was among those who challenged this act successfully in a lawsuit finally resolved in the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

Franklin edited his father’s autobiography, My Life and an Era, which Buck wrote by typing it out one word at a time, using only his index finger after suffering a difficult stroke, which left him with one side severely weakened. Franklin and his son, John Whittington Franklin, edited it after Buck passed away. It was published in 1997.

Franklin always looked at Tulsa as his only home, recognizing it as such in his autobiography, Mirror to America, in 2006. Franklin’s parents were both focused opponents of segregation and bias in all parts of their lives.

When young John Hope wanted to go to the Tulsa Opera, his parents refused to join him. “Go if you want, but we will never honor a segregated practice with our presence.” He went even though forced to sit in designated segregated seating. Later he said as much as he loved opera, he wished he had honored his parents by not going.

Franklin earned his doctorate in history from Harvard University and went on to teach at several universities, including Brooklyn College where he was the first African-American to head the history department.

That was followed with distinguished service elsewhere, including years as the head of the history department at Chicago University and at Duke.

His extensive research and writing earned him the respect of many and honorary degrees from over 100 colleges and universities. His history of African Americans, From Slavery to Freedom, is still the definitive work on African-American history and has sold over three million copies.

His biography of George Washington Williams was a brilliant reconstruction of the life of the first major African-American historian whose life had virtually been hidden in American history. Franklin’s focused scholarship and relentless detective work over several decades of research resulted in a masterpiece described as a brilliant and superb work.

In School Book Nation, the author, Joseph Moreau, described the relentless attacks on Franklin’s magnificent history textbook, Land of the Free. Franklin was singularly responsible for exposing and detailing the vast and brutal history of segregation and discrimination imbedded in the country’s history after the Civil War.

Slavery met its end, but its end gave birth to a complex and relentlessly brutal and vicious world of endless and humiliating barriers and assaults on humanity itself.

It was a crime in many southern states to teach or educate African Americans. They were not allowed to vote in the “white primaries” which were the definitive elections in southern states at the time.

Franklin personally felt the painful blow of discrimination from his early childhood when he and his mother were forced off a segregated train; being rejected as a guide through busy downtown Tulsa traffic by a blind woman who, when discovering that the Boy Scout who had rushed to help her was black, rewarded him with a demand that he not touch her because he was black; being threatened with lynching as a young man; being denied mortgage financing as a middle-aged man because of his race; being ordered to serve as a porter in a hotel when he was 60 and a guest at the same hotel; and at age 80 being directed to hang up a guest’s coat at a Washington club where he was not an employee, but a member.

He witnessed and honored the great gains made during his life, but to the end he witnessed and documented the insidious power of imbedded racism.

He dedicated his life to history and he followed the highest standards of professional scholarship in each of his works. He was very careful not to wrap any of it with emotional judgment, but to lay out the full truth, fact after fact after fact.

That and his extraordinary dignity was what added so much power to his words and led to his recognition by President Clinton as a recipient of our country’s highest civilian honor, the Medal of Freedom.

The PBS film, First Person Singular: John Hope Franklin, describes him as a legendary figure among American historians.

His legacy is unmatched and is sharpened and focused with each passing year, for he is truly one person, who in remembering him, the named one, we cannot forget the many without remembered names who suffered and survived so much.

– Don McCorkell is a Santa Barbara, CA-based documentary filmmaker who represented Tulsa in the state House from 1978-96. He earned both a bachelor’s degree in political and a law degree from the University of Tulsa.

Editor’s Note: This it the first in a series of essays commemorating the centennial of Franklin’s birth that will appear in the Oklahoma Eagle, a north Tulsa weekly that focuses its coverage on the African-American community. All of the essays on Franklin’s life, work, and significance as an intellectual, social and political force in America will appear at okobserver.org.