BY DAVID PERRYMAN

Oklahoma State Fire Marshal John Connolly was a man ahead of his time. He served in the early years of Oklahoma’s statehood and brought progressive ideas regarding fire protection and safety to the table. Unfortunately, even a man with the national respect and standing of Marshal Connolly was unable to budge the staunchly conservative attitude of the Oklahoma Legislature in time to prevent one of single most deadly fires in Oklahoma history.

Oklahoma State Fire Marshal John Connolly was a man ahead of his time. He served in the early years of Oklahoma’s statehood and brought progressive ideas regarding fire protection and safety to the table. Unfortunately, even a man with the national respect and standing of Marshal Connolly was unable to budge the staunchly conservative attitude of the Oklahoma Legislature in time to prevent one of single most deadly fires in Oklahoma history.

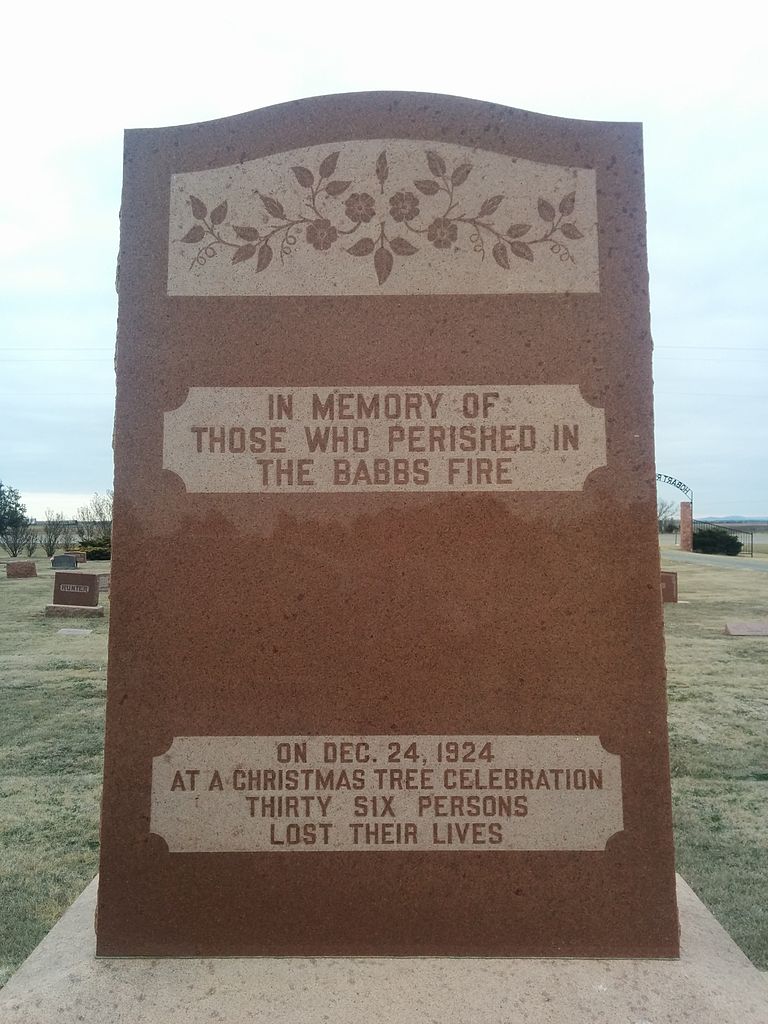

Ninety-four years ago this Christmas Eve, a horrific fire at the Babb’s Switch School brought Connolly’s warnings to center stage as Oklahoma, the nation and, indeed, the world mourned the senseless death of nearly 40 children and adults who had gathered for a school program and Christmas party about six miles southeast of Hobart in Kiowa County.

Much has been written about the fire over the past 94 years, but many documents of that era illustrate that much of the horror and ensuing heartbreak could have been prevented.

On the front page of the report issued on Jan. 26, 1925 by C.T. Ingalls, manager of the Oklahoma Inspection Bureau were the simple words, “LEST WE FORGET.” That report concluded that even without any aggravating circumstances, a simple structure with very limited defective and poor means of egress is a dangerous place for public assemblage.

Compounding that situation was a light frame structure made of pine wood and painted with oil based paint and a tinder-dry Christmas tree decorated with cotton and red and green lit candles. One door had been replaced with a coal chute that prevented egress and the other doorway had inward swinging doors that scraped along the floor. All windows were covered with heavy iron screens that had been bolted into place.

Only 12 minutes after the candles ignited the tree and spread to the ceiling and one of the glass kerosene lamps had exploded, the structure was an inferno where it was a miracle that as many of the estimated 150 to 200 in attendance escaped from the 720-square-foot building.

Only 12 minutes after the candles ignited the tree and spread to the ceiling and one of the glass kerosene lamps had exploded, the structure was an inferno where it was a miracle that as many of the estimated 150 to 200 in attendance escaped from the 720-square-foot building.

Since at least 1919, Fire Marshall Connolly had been promoting legislation to enact a statewide building code and a sufficient budget to enforce it. In Connolly’s Ninth Annual Report published that year, he illustrated that the high cost of annual insurance premiums across the state was a hidden tax that was greater than the cost of state government and would “build 500 miles of the very best hard-surfaced roads annually.”

Connolly reasoned that “building construction is at the basis of all fire prevention work” and “we need a State building code, a moderate law, which will empower the State Fire Marshall with concurrent jurisdiction in cities and towns having building codes” and which “would govern where local codes do not exist.”

His report further stated, “It would be impossible to estimate the benefits that flow from regulatory ordinances” and in the absence of regulations, “it subjects the community to the dangers of unsafe construction.”

Of course, Connolly was a realist. He was aware that, “Sensible men appreciate these facts, and it is only once in a while that you find a man who is so ignorant and unreasonable that he will oppose any attempt to restrict him, even when the public interest demands it. Such a man must be taught the lesson that his fancied rights must yield to the stern necessity of public safety.”

In January 1925 the National Fire Protection Association issued a report in its Quarter publication. In that report, Fire Marshall Connolly is quoted as saying, “The tragedy of the schoolhouse could have been prevented if Oklahoma had enacted a state building code.” But he reported, time after time, the Oklahoma Legislature had killed such a code in its committees.

Connolly’s earlier attempts to obtain information and inspect all one-exit wooden schoolhouses in the state ballooned to 400 inspection requestsby February 1925, but the Legislature did not act until 2009 – 85 years after the Babbs Switch School fire – to adopt the Oklahoma Uniform Building Code Commission, mandating a statewide minimum building code for all construction within the state.

One fire and safety issue that remains a problem is fire official access to vacant structures. State and local laws do not provide fire officials with a procedure to gain timely entrance into vacant structures that may pose grave fire hazards or contain substances that could endanger the lives and health of firefighters who might later be called to fight a fire there.

The National Fire Protection Association estimates that more than 20 civilians and 6,000 firefighters are injured while fighting fires in these properties every year.

Lest We Forget that fact, I plan to introduce a bill this session addressing those issues.

– Chickasha Democrat David Perryman represents District 56 in the Oklahoma House

Photos: Eric Johns/Creative Commons; Oklahoma Inspection Bureau