It’s an old joke: What do you call a person who knows three languages? “Trilingual.”

Two languages? “Bilingual.”

One language? “American.”

Yes, while much of the world has learned English, most Americans relentlessly refuse to learn a second language. There are about a billion more non-native English speakers in the world than the 419 million of us who were born into it.

In fact, most of the songs entered by the 40 countries in this year’s Eurovision song contest are sung in English and many songs that contain national languages are bilingual as well. Portugal to Albania to Bulgaria to Georgia, the artists recognize the lingua franca of the world.

And in 2012, Language on the Move reported only 46% of Europeans as monolingual. “Nineteen percent of Europeans are bilingual, 25% are trilingual and 10% speak four or more languages.”

Good on them. A 2019 study from the University of Alberta indicated that bilingual children were particularly adept with “their cognitive flexibility – the ability to switch between thinking about different concepts,” according to Elena Nicoladis, lead author of the study, as reported by Science Daily.

I remember my first trip to San Antonio 50 years ago. Walking around the Alamo on a Saturday morning, I was in a sea of Spanish speakers. “Oh, that must be how it feels to be in the minority.” Valuable lesson.

Of course, most of the shoppers I shared the sidewalks with were probably bilingual.

Every language on Earth represents a distinct worldview. Through the generations, different linguistic families have adapted their words and modes of expression to describe their particular worlds, thereby revealing what they consider important and in what ways.

Cultures create languages create cultures. We are a unirace with many valuable voices.

Thus, when Cristina Calderón, the last Yámana speaker on Earth, died in February, she took an entire heritage with her. Her people lived in Tierra del Fuego, land’s end at the tip of South America. Their perspective can never again be brought to bear on the one world we inhabit.

Tribal pride has encouraged many Native American nations to try to preserve or revive their languages and the worldviews they represent, trying to keep important information and insights from getting lost in translation.

Last year saw the first film shot entirely in the Blackfoot language of the Blackfeet of Montana. Brian D’Ambrosio, writing for The Missoulian, describes Sooyii as the story “of a young Pikuni man, Creature Hunter, witnessing the devastation wrought on his community from the horribly contagious spread of disfiguring, deadly smallpox.” There are also subplots touching on the conflict between the Blackfeet and Shoshone tribes and references to the epidemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women.

But with only 50 or so fluent Blackfoot speakers remaining, the script had to be taught to the actors phonetically, though those involved hope the film provides impetus for a renewed interest among other Blackfeet to learn their language.

Last year, writing for The Oklahoman, George Lang reported how the Cherokee and Comanche nations of Oklahoma were taking steps to protect their native speakers, all of whom were elderly members and thus at greater risk during the pandemic – which continues. At that time about 2,000 of the 385,000 Cherokee citizens spoke Cherokee. The Comanches reported 11 “fluent speakers” and two more who were “conversationally proficient.”

Writing at the time of Cristina Calderón’s death, Dolors Bellés of Barcelona’s El Punt Avui called the Yámanas, “An exterminated people victim of the colonizing genocide.” Her colleague, Carme Vinyoles, denounced all of the European and American colonizers and missionaries and whalers and poisoners and “Indian hunters” who massacred the natives for money.

Krisztian Kery, the director and writer of Sooyii, who grew up in Russian-controlled Hungary, was more even-handed in passing out blame for the decimation of cultures. “Shoshones learned about biological warfare and gained territory by wiping out people with smallpox,” Kery told D’Ambrosio. “If you survived, you were fine and you would never have it again. But the Shoshone used it as a method of wiping out different camps.”

“With Calderón’s death,” Bellés reiterates, “a culture disappears, a way of interpreting the world, a way of thinking.”

This threat is important to her and Vinyoles, who write from Barcelona, where Catalonians are besieged by threats and demands by the Madrid government and national courts, which try to limit the Catalan language and culture – and, of course, the Catalonian bid for independence.

They and the First Nations throughout the Americas realize that their very ways of life are in danger of going the way of Yámanas. The Scotsman also reported in February that, “Efforts to preserve Gaelic set for [a] boost under home recording studio project.”

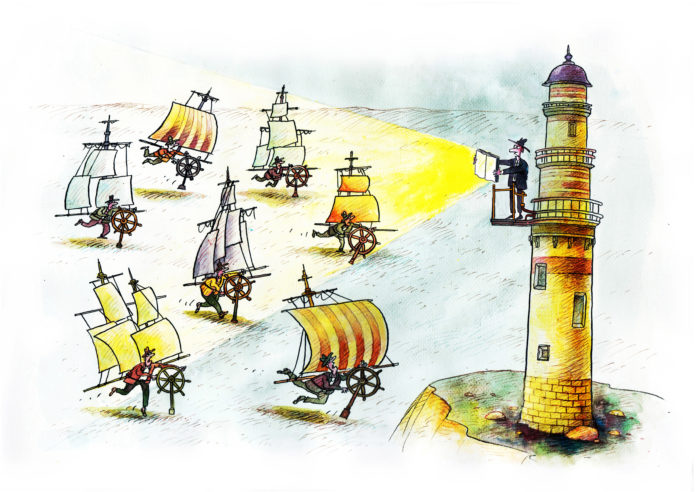

From a philosophical standpoint, the different languages and cultures are important in that they give us not only more, but more diverse, minds to examine the one Earth we of the unirace share.

From an individual standpoint, a University of Tokyo study last year revealed increased brain activity during the initial stages of learning Japanese. According to Science Daily, “The results show that acquiring a new language initially boosts brain activity, which then reduces as language skills improve.”

And, of course, this fortified brain ends up with more “stuff” in it.

“We all have the same human brain,” neuroscientist Kunihoshi L. Sakai is reported as saying, “so it is possible for us to learn any natural language. We should try to exchange ideas in multiple languages to build better communication skills, but also to understand the world better – to widen views about other people and about the future society.”

But our minds must be open enough to accept, digest and incorporate the insights of others into our own lives. When honest, we realize we don’t have all the answers. But we must be brave enough to admit our fallibility.