BY BRUCE PRESCOTT

American Christians have been divided over the relation of the Ten Commandments to government since 1635. That was when a Separatist Baptist minister who fled religious persecution in England was drug before the magistrates in Massachusetts Bay Colony for espousing “dangerous opinions” that threatened the peace and order of the colony.

American Christians have been divided over the relation of the Ten Commandments to government since 1635. That was when a Separatist Baptist minister who fled religious persecution in England was drug before the magistrates in Massachusetts Bay Colony for espousing “dangerous opinions” that threatened the peace and order of the colony.

The charge against Roger Williams, which he freely admitted, was that he proclaimed that civil government should only enforce the “second table” of the Ten Commandments – the last six commandments. The commands of the “first table” of the law – the commands regarding religion and worship – were matters of private, individual conscience. Williams was convicted and banished from the colony.

Roger Williams believed that there should be a “wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.” Likening compulsory religion to a spiritual rape, he insisted that genuine faith was a conscientious voluntary commitment. He was the first American advocate for religious liberty for everyone – whether, in his words, they were “paganish, Jewish, Turkish or anti-Christian.”

Williams went on to found the colony of Rhode Island and the First Baptist Church in the Americas. The charter that he and John Clarke, another Baptist, secured for that colony has been described as the first charter in the history of the world to secure “a free, full, and absolute liberty of conscience.” Among other things it guaranteed that no person would be “molested” on account of their religious beliefs.

In time, Rhode Island’s provision against being “molested” for religious convictions would make its way into the charters and constitutions of several other colonies and states, among them Oklahoma. But for more than another century, Baptists and other religious minorities suffered for their religious convictions. As late as the early 1770s jails in Virginia were filled with Baptist preachers whose only crime was “preaching without a license.” By law, only Anglicans or Presbyterians could get a license to preach.

That is why Virginia Baptists refused to ratify the proposed U.S. Constitution until an amendment was added that secured the right to religious liberty for everyone. When the Constitution with the First Amendment was finally ratified, John Leland, the leader of Virginia Baptists, rejoiced that it made it possible for a “Pagan, Turk, Jew or Christian” to be eligible to serve in any post or office in the government.

Baptists’ support for separation of church and state endured for nearly two more centuries. With this support, states like Oklahoma, populated with numerous Baptists, wrote state constitutions that made separation of religion and government even more explicit than in the U.S. Constitution.

Oklahoma’s state Constitution made sure that religion could never receive any tangible support from the government:

“No public money or property shall ever be appropriated, applied, donated, or used, directly or indirectly, for the use, benefit, or support of any sect, church, denomination, or system of religion, or for the use, benefit, or support of any priest, preacher, minister, or other religious teacher or dignitary, or sectarian institution as such.” [Section II-5]

How could separation of religion and government be made more explicit?

Baptist support for separation of church and state began to decline after the civil rights era. During the 1970s and early 1980s Bob Jones University and the IRS were engaged in a lawsuit over the constitutionality of the IRS’s denial of the school’s tax-exempt status. In 1970 the IRS ruled that contributions to private schools with racially discriminatory policies no longer qualified as charitable tax deductions under the provisions of the tax code. The school argued that denying them the right to discriminate on the basis of race violated their right to religious liberty.

Many prominent Southern Baptist ministers, along with several TV evangelists and conservative mega-church preachers from other denominations, were alarmed when the Carter Administration supported the IRS ruling. A number of them determined to organize political activists within their churches and institutions and then use them to exert influence on secular politics. The result was a fundamentalist takeover of the Southern Baptist Convention and the rise of the Religious Right.

The more successful their political efforts, the more they promoted the union of church and state. By 1998 Richard Land, then president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, was telling the New York Times that the Religious Right was tired of being taken for granted by the GOP: “No more engagement. We want a wedding ring, we want a ceremony, we want a consummation of the marriage.”

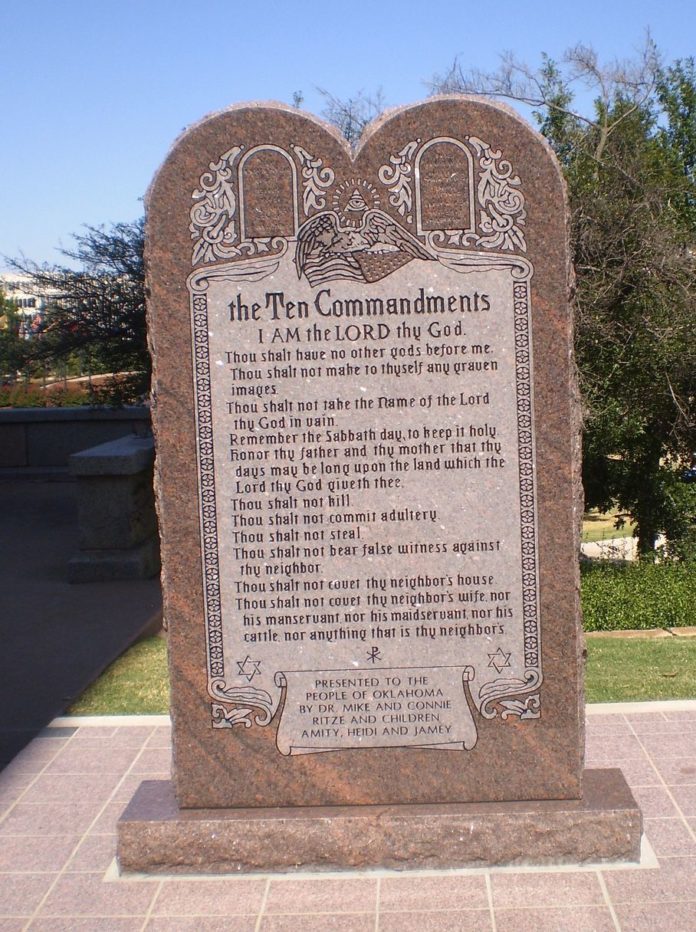

The Religious Right never got a ring. Diamonds were too small for a movement this size. Instead, they settled on granite. All around the country, large granite monuments became the symbol of an unholy union of pretentious piety and politics.

Erecting Ten Commandments monuments on public property – preferably at the state Capitol or on the courthouse lawn – became the sign that the marriage of right-wing religion and the local government has been consummated in that community.

Nowhere has the engagement of right-wing religion with government been more prominent than in Oklahoma and both parties have been desperate to effect a consummation.

The first attempt was a monument on the courthouse lawn in Haskell County, but elected leaders there proved too vocal about their intent to establish religion. In 2010, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled it unconstitutional and made them remove it.

Before that case was final, lawmakers approved of the erection of a Ten Commandments monument at the state Capitol. There, elected leaders deliberately attempted to circumvent Section II-5 of the State Constitution and key leaders were careful to describe the monument in secular terms as merely a historical artifact related to law. Public perception, however, has always been that the monument is religious nature.

I, an ordained minister, opposed placing this monument on public property and filed suit with the ACLU because I believe it is bad for religion. The Ten Commandments is a covenant between God and people of faith. The text mentions God six times and refers to “the Lord” seven times. It is obviously religious in nature.

Erecting the monument under sham secular pretenses serves only to trivialize the holiness of sincere religious covenants and undermines religion by negating the significance of the most sacred symbols of religious language.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court recently agreed that the Ten Commandments monument is not merely historical. The court said it is “obviously religious in nature.” The ruling also accused lawmakers of attempting to circumvent the clear intent of the language of the state constitution which prohibits the government from “directly or indirectly” providing support for religion.

This ruling is good for both religion and the government, but the verdict may not yet be final. Incensed that their consummation has been denied yet again, the governor is refusing to remove the monument and state legislators are threatening to either impeach Supreme Court justices or alter the wording of the state Constitution.

Obviously, two of the three branches of Oklahoma’s government are firmly in the hands of the Religious Right and now they are aroused again.

– Bruce Prescott, a Baptist minister, was one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit challenging placement of the Ten Commandments on the state Capitol grounds. He also is a member of the Oklahoma Observer Advisory Board.

Well said!