BY DAVID PERRYMAN

“Trudging stoutly along by the canal,” as the story goes, the 8-year-old son of a Dutch sluicer was returning home from delivering cakes to a blind man. Humming as he passed the dikes, he noticed that recent rains had made his father’s job even more important.

“Trudging stoutly along by the canal,” as the story goes, the 8-year-old son of a Dutch sluicer was returning home from delivering cakes to a blind man. Humming as he passed the dikes, he noticed that recent rains had made his father’s job even more important.

In fact, because a large portion of Holland was below sea level, the job his father did was essential. Sluicers faced the responsibility of manipulating the water levels by using a series of gates, dikes and canals to protect the villages and countryside from flooding.

The young boy was proud of his father’s brave old gates and their strength and pondered briefly how sluicers always referred to the danger of “angry waters” inundating the land. Suddenly the child noticed that he still had a distance to go and the sun was setting. He quickened his pace as he remembered nursery tales of children lost in forests.

Deciding to run the rest of the way home, he was just then startled by the sound of trickling water. Up the side of the dike he noticed a small hole through which a tiny stream of water was flowing.

Any child in Holland would have realized the danger, but no child was more aware of the “angry waters” than the son of a sluicer. “Quick as a flash, he saw his duty,” and almost before he knew it, he thrust his chubby little finger into the hole and stopped the flow.

Initially, he was proud of the fact that he was doing his part in holding back the “angry waters” and that his hometown of Haarlem would not be drowned while he was there. The remainder of the chapter entitled “Friends in Need” in Mary Mapes Dodge’s 1865 novel Hans Brinker; or the Silver Skates: A Story of Life in Holland illustrates the boy’s overnight experience.

The story relates the physical and mental anguish and the battle against numbing cold that the young boy encountered, awkwardly perched halfway up the dike all night long until he was discovered at daybreak, in pain and despair, yet alive and ultimately well, by a passing priest.

While the boy is never named, the author subtitled the story within the story as, “The Hero of Haarlem.”

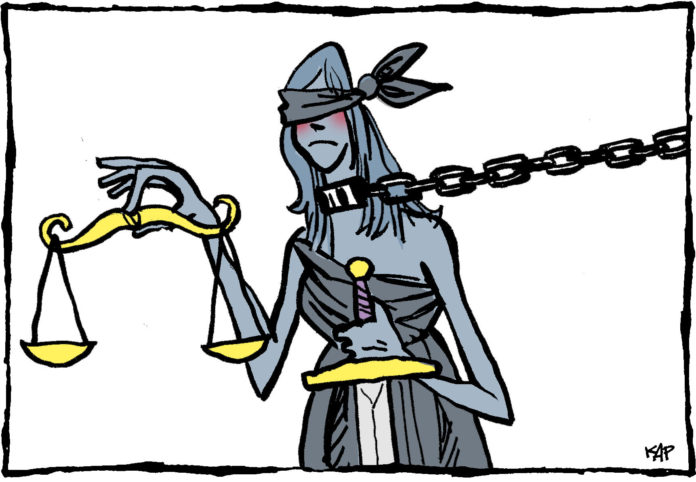

This legislative session, there is a desperate need for persons with the character of the young Dutch boy. There are a number of bills that need to be turned back like the “angry waters.” The bills deal with an overt attempt to politicize Oklahoma’s judiciary. Most were filed in response to the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s determination that last year’s Legislature failed to comply with the single-subject rule in the Oklahoma Constitution.

To understand the current situation, one must understand the not-too-distant past. For decades prior to the 1960’s, county and appellate judges were selected by purely political means and many judges served accordingly.

That is not to say that there were not good, honest men and women who served on the bench at various levels with the utmost integrity. However, the design of the system was such that judicial appointments were so politicized that undue influence was always a strong possibility and often a reality.

As a result, in the early 1960’s, the state was rocked by a judicial scandal of impropriety and corruption that reached the highest levels of Oklahoma’s judiciary.

With a goal of achieving a fair and impartial judiciary, Oklahoma’s Judicial Nominating Commission [JNC] was formed. The commission has worked well. It began functioning in 1969 and nominates a pool of three candidates out of which the governor may select one for appointment to fill vacancies on the Supreme Court, the Court of Criminal Appeals, the Court of Appeals, District and Associate District Judgeships, and the Workers’ Compensation Court.

The JNC has jurisdiction to determine whether the qualifications of nominees to hold judicial office have been met.

The JNC has 15 members who serve without compensation. Only six of the members may be lawyers. The six lawyer members are elected from six districts of the state by all of the lawyers who are from that region. Nine members are non-lawyers. Six of the non-lawyers are appointed by the governor, one from each of the districts. Of the six members named by the governor, not more than three can belong to any one political party and none can have a lawyer from any state in their immediate family.

One of the three remaining non-lawyers is appointed by the Senate President Pro Tempore, one is appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives and one is selected by the other members of the JNC. Of these three members, not more than two can be from the same political party.

The JNC was designed to be as free from partisan influence as possible and to allow litigants to be assured that the judge hearing their case would not be biased or beholden to either party or to an industry or special interest group. It has fulfilled that goal.

SB 1988 seeks to change the composition of the JNC by having the six lawyers on the JNC that are currently elected by their peers on a written ballot appointed in a purely political manner by the Speaker of the House and the Senate President Pro Tempore. Fortunately, a statewide outcry with calls and e-mails to the capitol stopped the bill from progressing out of Judiciary for the time being.

However, proponents of the change have inserted the language politicizing the process into SJR 21 and passed it out of the House Rules Committee by a 6-1 vote. While the breach created by SB 1988 has been plugged, citizens must keep their eye on it and also pay heed to SJR 21.

According to the storyteller, the spirit of the sluicer’s son represented the spirit of Holland in that, “Not a leak can show itself anywhere, either in its politics, honor, or public safety, that a million fingers are not ready to stop it, at any cost.”

Oh, for that spirit to be present in Oklahoma.

– David Perryman, a Chickasha Democrat, represents District 56 in the Oklahoma House of Representatives