About a year ago, I complained to my dentist that the bottom right of my tongue was bumpy and tender. I was having some dental work done, and my bottom teeth were rough and uneven. I was hoping a little filing could fix the problem.

“I think your oral surgeon should have a look at this,” he said. So I made an appointment, and based on my dentist’s suggestion, I asked for a biopsy.

The oral surgeon didn’t think that was necessary. The bumps were mostly white except for the one area I was constantly dragging over my lower teeth. He prescribed a mouthwash and a follow-up.

I went ahead with the dental work, and the mouthwash helped a little, maybe. Then, in the summer, a new bump showed up. This bump hurt every time it hit my teeth. I called the oral surgeon and, again, asked for a biopsy.

When I showed up for the appointment, he had a pathology report from my file, a report I had never seen from a visit several years earlier. It showed dysplasia on the underside of my tongue. He sent me straight to an ENT to have the bump removed.

I scheduled the surgery. Instead of a simple biopsy, he was going to remove the entire bump, including the margins around the bump, two surgeries for the price of one.

A week after the surgery, when I was still drinking my meals, painfully, he told me he was pretty sure he got it all even as he was explaining what the all was, a spindle cell sarcoma.

“They’re more aggressive than other squamous cells. We are suggesting radiation.”

I made an appointment at a cancer treatment center for a second opinion. I mean, radiation is pretty radical. They were more radical still. Their suggestion was another surgery because they weren’t sure, based on the pathology, that the initial ENT had, indeed, got it all. In the meantime, there was a new bump at the base of my tongue.

The new bump was a squamous cell tumor, and I agreed to the surgery that would remove a chunk of my tongue. The tongue would be rebuilt with tissue from my wrist, and my wrist would be grafted with tissue from my upper arm.

In addition to almost half my tongue, the doctor removed 14 lymph nodes from my neck. I spent three days out, receiving nutrients and oxygen from tubes running through my nostrils. When they brought me around, there was a leech on my tongue keeping the blood flowing, my husband and daughter were hovering over me, and I had no idea that three days had passed. I spent a total of seven days in the hospital.

Three weeks later, I’m still drinking all my meals. And I’m thinking.

What if I’d known about the dysplasia?

Could the knowledge that cancer was a possibility have changed when I got treatment?

I’m scheduled for radiation. And knowing what I know now, I’m also scheduled to have a stomach peg so I can get enough nutrients during the painful radiation process. It’s hard enough now to get the calories I need as the rebuilt tongue heals.

This is just one example of the time and money spent, and the extra pain endured, because the U.S. medical system doesn’t focus on prevention. What if I’d known about the dysplasia? What if I had regular checkups to make sure it wasn’t progressing and, at the first sign that it was, I’d been treated? Could I have been saved two tongue surgeries?

That’s supposing I had all the information I needed to make the right decisions. Medical decisions should be made by both professionals and patients. Both need to be educated. Prevention needs to be covered by insurance, or better yet, covered by a universal system that favors prevention over catastrophic fixes.

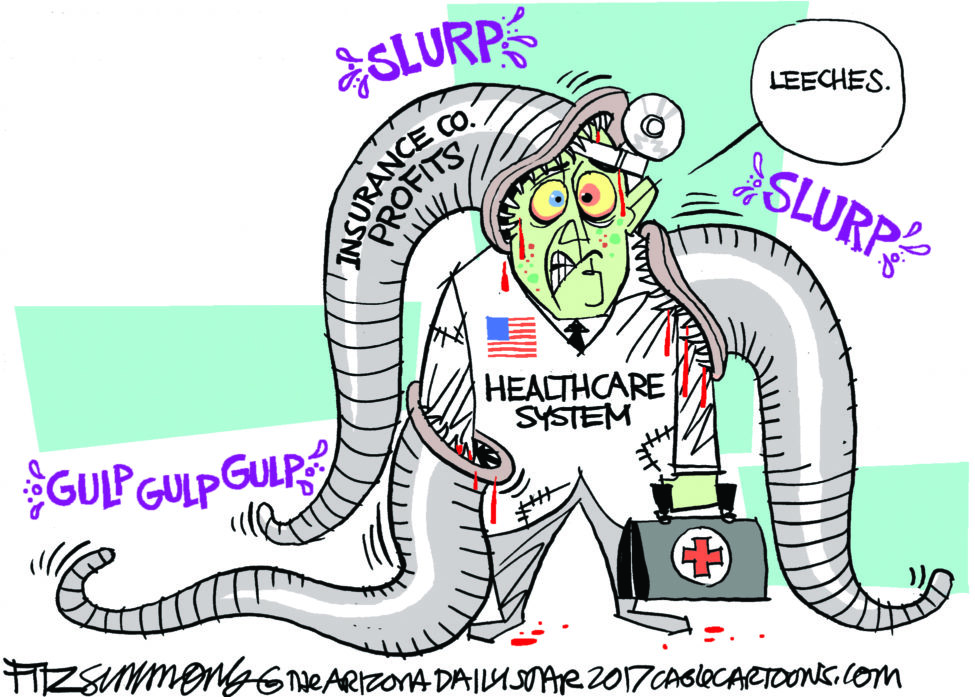

For those who think universal healthcare is too expensive, remember, the ounce of prevention costs far less than the pound of cure. A healthy workforce is essential to a sound economy. And making a fortune off the misfortunes of others, well, that’s greed. The last time I looked, greed was still one of the deadly sins.

Meanwhile, I’m drinking my meals and dreaming of a day when I can have a salad.