BY ARNOLD HAMILTON

Thirty-four years ago, Oklahoma was rocked by scandal.

Thirty-four years ago, Oklahoma was rocked by scandal.

A federal investigation implicated county commissioners in 60 of the state’s 77 counties in kickback schemes and other official corruption that cost taxpayers hundreds of millions in artificially inflated prices for roads, bridges, equipment and materials.

Today, Oklahoma could be sitting on a similar powder keg – more than 900 small town water systems and rural water districts that cannot afford professional expertise to ensure new construction and maintenance programs they’ve been assured they need are truly necessary.

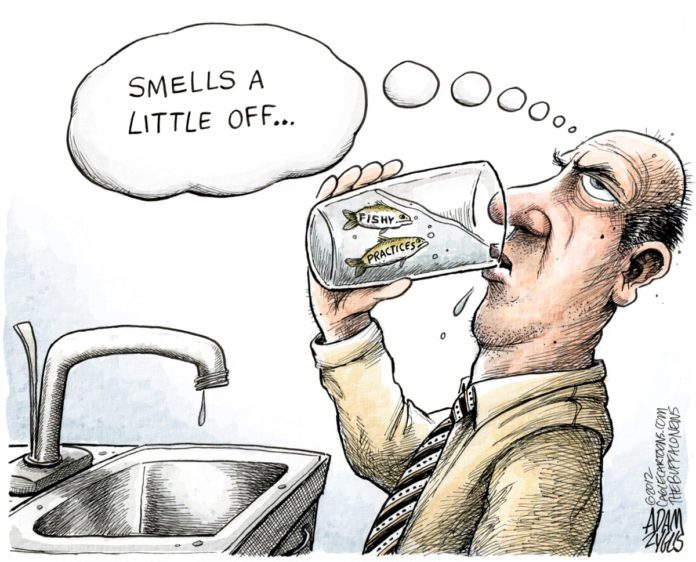

In fact, some consultants say privately they’ve seen multiple cases where big engineering firms have sold smaller water systems on Mercedes-style upgrades when what they really needed was the equivalent of a Hyundai.

They call it “speculative engineering.”

The result is that some water systems struggle to repay construction loans – many secured through state and federal programs – despite significantly raising rates to customers.

At least one would-be whistleblower reports meeting with the FBI on multiple occasions, sounding the alarm about suspicious projects. But it’s not clear whether a formal inquiry is underway.

Some worry that Justice Department higher-ups are resistant to turning FBI agents loose, fearing the trail could lead to politically well-connected Oklahomans. U.S. attorneys are political appointees, after all.

Typically, water systems need significant construction and maintenance investments about every eight years, meaning annually about 110 such projects are launched statewide.

In communities of 10,000 or more, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board is the big player – financially about $20 million in projects annually.

Improvements in the smallest, most impoverished areas often are financed with federal loans – about $15 million annually – administered by U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development. The agency also handles about $10 million yearly in water project grants that do not have to be repaid.

A major concern is that – much like the set-up that led to the county commissioner scandal – Oklahoma’s small town water systems and rural water districts often operate in a vacuum, technical checks and balances absent.

According to some engineering consultants and water system experts, local operators often rely primarily on the expertise of engineers that want to build projects. Fox guarding the henhouse?

State and federal agencies, if consulted, tend to operate independently of each other, meaning everything from environmental concerns to capacity issues to engineering proposals are rarely reviewed holistically.

In addition, it appears no hydrogeologists are consulted or employed to ensure there is sustainable, quality water available for the life of each project – a problem that has plagued more than a handful.

Arkansas, by contrast, gets all stakeholders together monthly to review the projects – a “much more comprehensive” approach, according to one consulting engineer who requested anonymity. “There’s a planning downfall in Oklahoma, something terrible.”

The closest Oklahoma comes to gathering the stakeholders is the quarterly meeting of the Funding Agency Council, which includes such groups as USDA Rural Development, the Oklahoma Rural Water Association, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board and Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality.

The agencies, however, review which of them is best positioned to help make the project a reality – not at the technical aspects to determine if the project is realistic and warranted.

Sometimes neighboring water systems don’t know what the other is doing – or what it’s costing.

For example, two adjacent Locust Grove-area water systems built projects within about a year of each other recently – both using roughly the same amount of pipeline, the same sized pipe and the same specs. One cost $6 million, the other $12 million, according to a water systems consultant who also asked not to be identified.

In Lincoln County, the expert said, a water district spent $125,000 drilling a well that turned out to be too high in iron and magnesium to serve the 300 residential users.

Drilling a test well would have tipped officials to the problems, but it apparently wasn’t done. The only alternative to use the well was to build a $2 million to $3 million water treatment plant.

The stories conjure bad memories of the county commissioner’s scandal that burst into public in 1981.

Heralded as the nation’s biggest corruption case, the federal investigation resulted in 230 convictions or guilty pleas, including 110 sitting county commissioners charged with federal crimes.

When the case finally wrapped up, then-U.S. Attorney Bill Price claimed prices of equipment that counties purchased had dropped as much as 42% – or $200 million in the four years after the probe was launched.

A series of state-initiated reforms, aimed at preventing such future mischief, included establishing a county purchasing office, requiring counties to use the state’s central purchasing and requiring all county officer attend county government training.

Further, counties were urged to retain the services of an engineer and to engage in long-term planning.

Ryan McMullen, a former state representative who is state director of USDA Rural Development, said his agency works primarily with the smallest, most impoverished towns and water systems – no communities above 10,000.

A primary goal, he said, is to keep “them from buying more of a system than they need … that makes our loan riskier.”

Among the factors considered: “What the possibility is of growth or the possibility of continued population decline … I wouldn’t call it adversarial. We are the check in that check-and-balance to make sure they’re not buying more of a system than they need.”

McMullen said only “a handful” of the agency’s loans are currently in default – on average “maybe one or two a year.” Most times, he said, the agency can re-amortize the loan so water systems can afford the payments.

Some independent consultants and water system experts say, however, they believe neither the federal agency nor state officials have the manpower in these lean economic times to give each proposal as thorough a review as needed.

Indeed, McMullen concedes he’s lost a third of his workforce to budget cuts over the six years he’s been USDA Rural Development’s state director. His agency now administers $700 million-plus in programs annually with a staff of only 64.

The concerns expressed by consulting engineers and other system experts cry out for further, systematic review – to ensure the taxpayers and ratepayers aren’t being taken advantage of.

Otherwise, Oklahoma could experience déjà vu, all over again.

– Arnold Hamilton is editor of The Oklahoma Observer. This report first appeared on the cover of the July 2015 Observer.