Review by John R. Wood

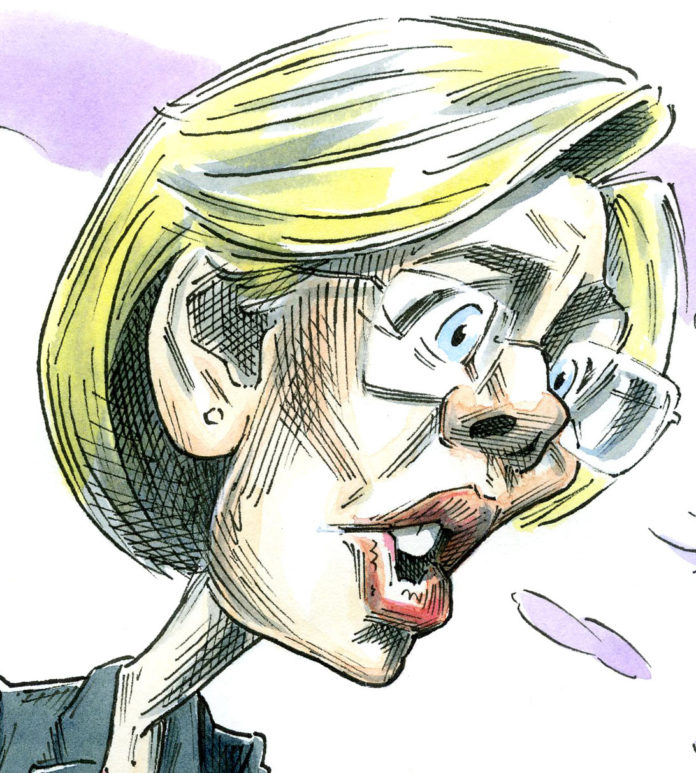

A FIGHTING CHANCE

By Elizabeth Warren

Henry Holt & Co.

384 pages, $28

It seems that junior Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren is taking over the mantle as the fierce new “Liberal Lion” of the Senate, a title carried by the original “Liberal Lion” Ted Kennedy who owned the same seat for nearly 50 years.

Warren, of course, is a native daughter of Oklahoma who was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 2011. She left Oklahoma after graduating from OKC’s Northwest Classen High School, accepting a scholarship to George Washington University on the way to her long career as both a consumer advocate and agency head, and now U.S. senator.

Warren’s new book – the former Harvard law professor’s ninth – is called A Fighting Chance. It seems the book’s title harkens to a time she says is now past – a time when families of modest incomes, that worked hard and played by the rules, had at a fair shot at the American dream.

Today, she says, “Here’s the hard truth: America isn’t building that kind of future any longer.”

Her troubled upbringing shaped her focus on the unraveling of the middle class. In this book she does not seem to pull any punches, charging the economic arena is certainly “rigged” – banks are in cahoots with big-money, resulting in a rising rate of anxiety in the middle class and, in turn, a near total loss of faith in the American Dream.

Her public fights were certainly personal: She switched parties from a “Goldwater girl” when she lost faith in the market system in the 1990s. Unfortunately, she merely glosses over this important transformation with just passing detail. She did say that she always was “on the lookout for cheaters and deadbeats as a way to explain who was filing for bankruptcy.”

But her research led her to find something she didn’t expect: 90% of the time people go bankrupt for one of three reasons: 1] a medical problem; 2] a job loss; or 3] a family breakup [divorce or death]. What’s more, she found that most people felt that bankruptcy was a personal failure; therefore, they didn’t take it lightly as portrayed by the banks.

Warren’s premise is not surprising in that there is a loss of faith in the American Dream. Data shows it is much easier for people outside the United States to rise from the class of their birth – including in Australia, Japan, Germany, and the Scandinavian nations, according to Russell Sage Foundation Fellow Economist Miles Corak’s research from University of Ottawa.

Warren’s book details how her life story and her rather public clashes – beginning in the 1990s on a national commission reviewing bankruptcy laws as a Harvard Law professor and later as a U.S. senator – led to her philosophy of how government can give someone who is under the thumb of the 1% a fighting chance.

Warren traces this “rigging” of the system to the early 1980s, which was the start of the deregulation era of the financial system that resulted in the mortgage crisis. By 2008, big banks had over time recklessly bundled precarious loans into securities they then unloaded to unwary investors.

Warren’s book is will keep you turning the page, or touching your kindle screen, because her storytelling quickly connects to the reader with her well-paced narrative.

Her autobiography moves from her childhood to stories of her fighting to set up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and her fights with the credit card industry, as well as her underdog win against Republican Sen. Scott Brown in which she reclaimed the late Sen. Kennedy’s seat for Democrats in 2012.

Her win was helped by a simple agreement between the two candidates: if the opponent had a Super PAC ad, each candidate would “dip into our own campaign contributions and give money to charity.” So, the League of Conservation Voters were in check with the much larger American Crossroads [Karl Rove’s Super PAC]. This “People’s Pledge” worked and no outside money came into the campaign via ads. Maybe, this “People’s Pledge” should be used for the 2014 campaign season!

Warren’s success can be attributed to her populism and hard-nosed persistence. Though the deck may be stacked, she says it is certainly still possible for the little guy to win, pointing to the new consumer protection agency she helped create.

Unfortunately, at the time, her fire-brand ideas kept her from moving from interim director to full director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. At the bureau, she poked her finger in the eye of too many banks, which were amply scared of her populist rhetoric and actions in protecting the public from predatory banking practices and exorbitant credit card interest rates, legitimized by the courts and Congress during the 1980s and 1990s.

Her anger is palpable: “Gradually [the bankers’] strategy emerged, target families who were already in a little trouble, lend them more money, get them entangled in high fees and astronomical interest rates, then block the doors to the bankruptcy exit if they really get in over their heads.”

During her Senate campaign, she set up numerous coffees across Massachusetts. At one such coffee, a person recorded her, and it became a YouTube sensation. At this coffee, she heatedly exclaimed off-the-cuff, “There is nobody in this country who got rich on their own. Nobody. You built a factory out there – good for you. But I want to be clear: You moved your goods to market on roads the rest of us paid for. You hired workers the rest of us paid to educate. You were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for. You didn’t have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything at your factory … Now look. You built a factory and it turned into something terrific or a great idea – God bless! Keep a hunk of it. But part of the underlying social contract is you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid who comes along.”

I like this speech, as unpopular as it may be, because it shatters a founding myth of the “self-made” man. It reminds me of Miller and Lapham’s Self-Made Myth. This myth originated in early America in which individuals wanted to set themselves apart from Europe’s pedigreed aristocracies who offered little optimism for individual success. However, Horatio Alger’s stories, essentially variations on Ragged Dick, a rags-to-riches narrative, seemed to strike a rather profound chord in the American psyche.

In reality, individuals and businesses cannot prosper without specific infrastructure in place, such as public transportation, the public education system, the U.S. postal service, public safety, taxes for the public good and other laws and regulations, etc. George Lakoff calls it “investing in the common good for the common wealth.”

Miller and Lapham argue that when one recognizes and admits the many ways in which entrepreneurs benefit from these pre-existing systems, taxes are seen more clearly as a way to financially support the structures which helped these individuals create their wealth in the first place. Instead of this self-made man, and “We built this,” mantra from the Romney campaign, there is actually a “built-together” reality for the common good.

This “self-made” man illusion is often at the heart of how we shape our public policy decisions.

Currently, America has a fairly robust economy strictly because of our public infrastructure that supports it. In all, we have order and stability, one that is predictable with long-established rules for ownership and investing, as well as methods and procedures to resolve conflicts.

In today’s world, business entrepreneurs rely on this predictability to have confidence that these rules today will be the same next year and the year after.

Public education provides a skilled workforce investment in public education. The military, police, and fire services provide for protection and safety. Our military, with the labor of the public sector, created the interstate highway system as well as the backbone of the Internet, what was once called ARPANET. This is what Miller and Lapham call, the “built-together reality.”

Warren’s speech also touches on and critiques the myth of John Galt, Ayn Rand’s imaginary hero, where everyone is supposed to be – as we call them today – “job creators,” who seem to think that they did it all themselves, ignoring everything that brought them there again – infrastructure, clean air, water, protection and safety, largely from investments in the common good.

This acknowledgement of the common good that we all rely on seems to make some folks queasy. For example, I find it interesting that on cronycapitalism’s Facebook page, Warren is angrily, incessantly critiqued as a “socialist” for her most famous quote.

Let’s make things clear – she is not a socialist. Wikipedia defines socialism as “an economic system characterized by social ownership and/or control of the means of production.” So, how is providing public goods, such as roads, police, bridges, education socialism? You realize, in America these public goods attempt essentially to do those things that actually complement private markets and not at all characterize government production. Public goods actually enhance economic activity by entrepreneurs.

So let’s not call public goods “socialism!”

When Warren worked at the Consumer Protection Agency, she also was accused of being a socialist. Her reaction: she’s not one; instead she’s a capitalist who believes that markets work best only when “there really is a level playing field where both sellers and their customers understand the terms of the deal.”

That’s not socialism, that’s transparency in a regulated capitalism.

Warren explains further in her book: “We can’t bury our heads in the sand and pretend that if ‘big government’ disappears, so will society’s toughest problems. That’s just magical thinking – and it’s also dangerous thinking. Our problems are getting bigger by the day, and we need to develop some hardheaded, realistic responses. Instead of trying to starve the government or drown it in a bathtub, we need to tackle our problems head-on, and that will require better government.”

Warren’s book reveals a lifetime of passion and hard work, and some luck thrown in as well. And, in the end, even if painfully slow, maybe one person really can make a difference. But we make better choices when we acknowledge our past investments in our common good as well as thinking about future commitments, all of which are required to make personal initiative thrive.

Warren wants America to be a place where everyone gets a shot, much like she did.

A fighting chance.

– John R. Wood, PhD, is a political science professor at Rose State College.

Editor’s Note: Former state Rep. Wanda Jo Stapleton offers her take on Sen. Warren’s new book in the June print edition of The Observer.