BY HARRY T. COOK

When we were children, we tended to think that what obtained in our “now” would be maintained forever, that we would never leave our parents, nor they us. Without much thought, we assumed that the home in which we had found emotional and physical comfort would never change, that it would always be there for us.

When we were children, we tended to think that what obtained in our “now” would be maintained forever, that we would never leave our parents, nor they us. Without much thought, we assumed that the home in which we had found emotional and physical comfort would never change, that it would always be there for us.

To us as 7-year-olds, a minute was like an hour, and hour like a day, a day like a week, a week like a month, a month like a year, a year like a century we could scarcely imagine.

Now that we are adults – in my case, approaching 74 years of age – it works in reverse. We wonder how it got to be one o’clock in the afternoon already when it seems as if we just sipped our morning tea or coffee. How can it be almost Christmas? How can it be my birthday again so soon? How can my oldest grandchild be approaching her 15th birthday and driver’s ed?

What we are discovering is that much is fleeting and nothing is permanent, that, as one of the ancient Isaiahs said, “The grass withers, the flower fades. Surely the people is grass.”Or as we learned in Latin I: Sic transit gloria mundi.

Reading the work of such historians as Norman Davies and Jared Diamond is like falling out of a feather bed onto a cement floor. Davies merely tells the truth about empires that rose and whose emperors believed with all their hearts would never fall. Diamond documents the ending of civilizations due to conflict, climate change and epidemic.

Both bear witness to the perishing of once great city-states. Davies cites Thomas Hobbes’ blunt assertion that “nothing can be immortal, which mortals make.”

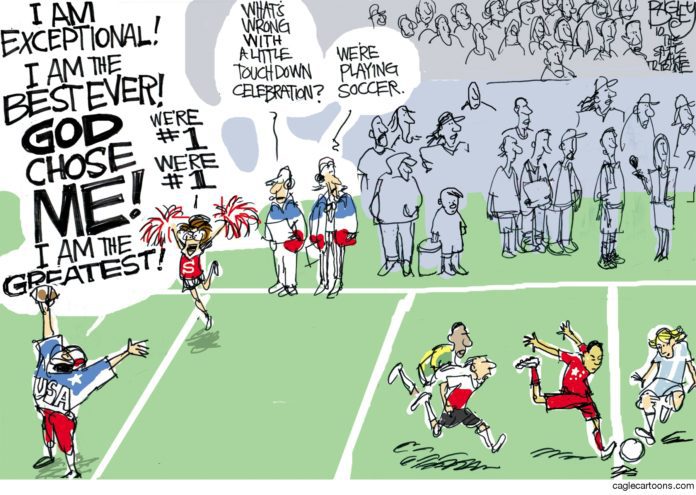

Yet, many American adults remain children in at least one respect: They do not or will not see an inevitable end to the empire they have known, by which I mean that entity which has existed officially since 1789 and unofficially since 1607.

This land had been home to those of the several Native American cultures that flourished here until their brutal removal by forced migration or out-and-out murder at the hands of European immigrants. The so-called Indians put up a fight, because they believed the land would be theirs forever. Read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha for validation of that point.

Among the generations that followed from the Massachusetts Bay and Jamestown immigrant communities, whose descendants had prevailed in the War of Revolution and for all intents and purposes created a new nation from the bottom up, the sense of a robust exceptionalism took root.

An aspect of that exceptionalism is expressed in Katherine Lee Bates’ “O beautiful for spacious skies,” which speaks of “patriot dream,” of the gleam of alabaster cities “undimmed by human tears” and the crowning of good with brotherhood all under the mercies of a commonly imagined god.

Bates wrote the verse in 1896. It was published in 1898 just as America the Beautiful had picked a fight with Spain and won as spoils not only Cuba but the Philippines. As a result, many eyes in both island nations were flooded with human tears, not to mention those shed by the poor souls trapped in the wretched slums of American cities during that same era, as described by Jacob Riis in How The Other Half Lives.

None of that withstanding, in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt sent the U.S. Navy’s fleet around the planet. It was meant to be a message to the world that a heaven-blessed empire was rising and here to stay.

With the carnage of the War Between the States at a half-century remove in national memory and with the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression yet to come with two world wars as bookends, things looked pretty good. Walter Lord demonstrated as much with telling narratives in his book The Good Years: From 1900 to the First World War. Vietnam, 9/11 and the quagmire of Afghanistan were unforeseen.

These latter three catastrophes are seen by some now and will be seen perforce by most eventually as signs of imperial decay and forerunners of ruin. Who knew that Rome’s crushing defeat in the Battle of Teutoburger Wald in 9 BCE would turn out to be the first major fissure in the fabric of an empire that would come to final collapse, according to Edward Gibbon’s analysis, 485 years later in 476 CE?

By the same lights, who would have thought in 1928 that “Detroit the Dynamic,” the nation’s much celebrated “Fourth City,” the Silicon Valley of its day, just 40 years on would begin a precipitous decline toward its present state of near-bankruptcy, its schools an educational joke, its streets in some places no safer than those of Damascus or Gaza, so much of its 139-square-mile expanse a lunarscape of ruin?

History’s verdict is that the disintegration of Rome was the result of such internal rot coupled with badly conceived, badly planned and badly executed wars. All of this has been told and re-told to generations of those who have studied history, including those who cannot or will not understand that it is a warning.

It is a warning not necessarily intended as a spur to the cleaning up of an act, rather that, as Hobbes observed, “Nothing can be immortal, which mortals make.” Or as parents have ever said to their holiday-besotted children at bedtime on Christmas night: “All good things must come to an end.” In fact, my mother spoke those very words to me at my bedtime on Christmas night 1952. How true they were. By Christmas 1953, she had been dead almost four months, leaving a family lost in grief.

The American civilization is young as world civilizations go. It is difficult for many Americans to foresee a time when the United States may discover the decrepitude that has been eating away at its innards for some time now might by then be past amendment. Yes, certainly, the United States has come an admirable distance in dealing with its racist past in the abolishment of slavery, in its progress with regard to women’s rights and in making child labor illegal by first seeing it as immoral.

However, in the recent choosing of its leaders, the American electorate has committed such mind-numbing errors as electing George W. Bush not once but twice, by allowing into the institutions of its various levels of government those still un-reconciled with science, know-nothing obstructionists, religious fanatics and such bellicose types as would lead the nation into war after war to prove that America is and must be über alles.*

The Tea Party and its revolt against government in almost any form together with the hold it seems to have on a still-defiant majority of Congress is bad enough. When paired with a public that always wants more and more of everything for less, viz. supersized portions of fatty foods, faster cars and glitzier sporting events, a society is exposed as fatally vulnerable – a society that verges with part of its schizophrenic self on anarchy and, on the other, self satiation, not only with unhealthy materiality but that which counts for nothing.

Such conditions spell the beginning of an end, because, as history has inexorably revealed, and as my mother explained in words the greater meaning of which she probably didn’t appreciate at the time, “All good things must come to an end.” Although she might not have thought the Tea Party to be part of those “good things,” nor, as the Calvinist she was, the current national self-indulgence.

Beyond moral judgment, who thought during the times of their triumphs that Pharaonic Egypt or Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon or Cyrus’ Persia or the Empire of Alexander Magnus would become only names in history texts? Or like Carthage, completely buried under the wind-sculpted sands of northern Africa, reduced almost to myth?

At one time long ago, I was possessed of the conviction that my parents would never leave me. Both did – in death. That’s a microcosmic glimpse of the truth about things as they are.

In that regard, it has occurred to me that the fathers of the church in their times may well have understood that finitude is the best for which humanity can hope. Maybe the notion of immortality, which could be attained only through obedience to moral imperatives said to have come from on high, became key to maintaining a relatively civilized society. If that is the case, the church, even with all its drawbacks, has performed a noble service.

Yet, no righteousness achieved through catechesis could gainsay the reality that there is an end to every thing and to all things.

*Google: The Project for a New American Century.

– Harry T. Cook is an Episcopal priest, journalist and author living in Michigan. His essays appear regularly in The Oklahoma Observer.