The happiest, healthiest, most educated, least corrupt, most equitable, and most ecologically sustainable counties are also the strongest democracies in the world. In these countries there is almost no focus on the need for a “strong leader.” A society does not need a “strong” leader when its systems of justice and political participation are strong and when its economic systems are fair and equitable. The search for a “strong leader” is a phenomenon of a failing society.

The desire for a strong leader is a symptom of a weak democracy. Strong democracies don’t seek strong leaders. They seek good, compassionate, ethical, non-corrupt, empathetic, responsive, and responsible leaders.

Most persons who boast about being strong leaders are a danger to democracy because they think it is more about them than the people they are representing. The self-description of “strong leader” is typically the language of despots and autocrats, not the language of good and competent leaders in a vibrant democracy.

People living in flawed or failing democracies like the United States may crave a strong leader owing to a sense that things are falling apart in society and a lack of confidence that a flawed political system can change things. In such a context, persons may long for a strong leader who they think can fix things that no one else or very few people can. This sets the stage for the ascension of narcissistic autocrats with an “I alone can fix this” attitude who are able to ride the wave of populist discontent to political power.

The problem is that very few if any self-described strong leaders are really in power to fix things for the people. Rather they are in power to satisfy their own egos and desire for gaining, maintaining, and expanding their own power. They are much more likely to spend the majority of their time and energy on maintenance of power rather than solving real problems for ordinary people.

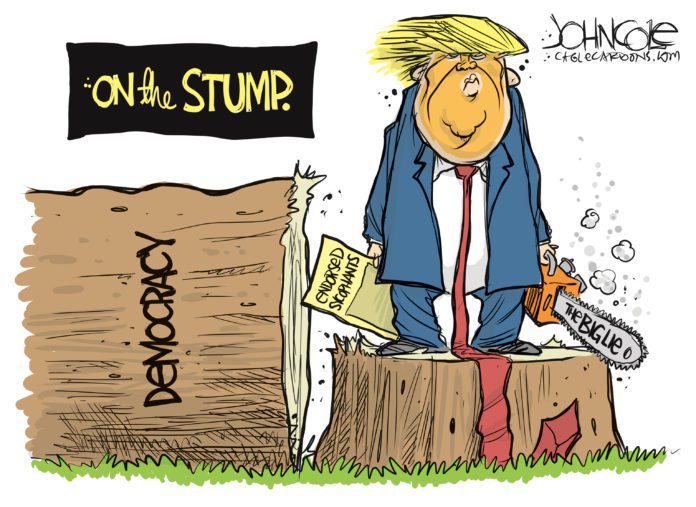

Instead of bringing real solutions, “strong” leaders tend to use propaganda to make people believe things are better when they actually are not, and they look for ways to take the attention of persons away from the unjust systems and practices that need to be transformed in order to make positive change possible. These strong leaders will often attempt to dismantle any barriers to or checks on the expansion of their own power, further weakening the systems, structures, and safeguards of democracy.

The cruel irony is that flawed and failing democracies are most prone to the lure of strong leader autocrats precisely when they should be most fully engaged with repairing democratic systems rather than falling into the temptation of believing a strong leader will make things better.

If nothing else, one can hope that the United States’ embrace of a self-described “strong leader” and our experience of his selfish and desperate attempts to hold onto power at all costs, even to the point of inspiring a violent insurrection and threatening democracy itself, might lead enough of us to recognize that we don’t need a strong leader. What we need is a strong democracy.