Updated at 3:04 p.m. 11.22.13

BY RICHARD L. FRICKER

As the anniversary date of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy approached I asked some of my friends and colleagues to provide their remembrances of Nov. 23, 1963.

As the anniversary date of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy approached I asked some of my friends and colleagues to provide their remembrances of Nov. 23, 1963.

JANIS WINOGRADSKY is an Emmy Award-winning journalist who has reported for both American and Australian television networks. She lives in Atlanta with her daughter, Grace:

I was very young [in elementary school] when Kennedy was killed. I was too young to really understand this heinous act of murder, the finality of death, and certainly did not have any idea of the enormity of what was happening. I experienced this event only through the reaction of the adults around me. Teachers were whispering and crying, not able to contain their shock and sadness. This was frightening to observe. And confusing. I actually thought maybe my parents had died and they were figuring out how to tell me. [I was 10 – it was all about me.]

Things were not much better when I got home. My parents were never very good communicators. Lack of communication breeds fear – this is the overriding feeling I can recall from this time. I remember staying home from school and watching the funeral on TV, and thinking that no one was ever going to be allowed to be happy again.

MARTIN KILIAN was born in Germany and emigrated to the United States over 20 years ago to study at the University of Georgia where he earned a doctorate in American Studies. As a career journalist he has been Washington, DC Bureau Chief for Der Spiegel, American correspondent for Swiss, German and Austrian newspapers and is American correspondent for the Swiss daily Tages Anzeiger. He has authored several books on American lifestyle and politics. He and wife Sylvia live in Charlottesville, VA. They have taken American citizenship:

On Nov. 22, 1963, I had just turned 13 and was living with my Mom and my Dad in the small city of Weinheim near Heidelberg in southern Germany. Because the assassination happened at 12:30 p.m. Dallas time, it was already 7:30 p.m. Central European Time. It had been dark for several hours, as the daylight in Germany in late fall and winter ends at 4 p.m. or shortly thereafter.

I had been with friends from school and came home for dinner to find my Mom crying. “President Kennedy has been shot,” she said.

What a shock! Kennedy had left a deep impression on the Germans when he visited Berlin and declared himself “a Berliner.” People really loved him. On top of that there was the worrisome question if the Soviets might be behind the shooting in Dallas.

After all, the Cold War could turn into a hot war – and Germany would be the frontline in such a war. So while Dad was still at work, my Mom and I stayed glued to the TV. Normal programming had been suspended, and later that evening the horrible news came: The American president had been killed.

I remember how fearful I was: What did that mean for the fragile state of affairs between the Americans and the Soviets?

The next morning at school there was only one topic: The murder of John F. Kennedy who had been a friend of Germany.

BOB YATES holds a law degree and formerly practiced in California before taking up journalism. He is former editor of the American Bar Association Journal. Yates continues to be a freelance editor and writer. He and his wife Kathy live in Chicago:

I was a freshman at the University of California-Santa Barbara. For some strange reason, I noticed what an absolutely beautiful day it was. I was finished with my morning classes, gathered up my bed linens and walked over to the laundry to exchange for clean linens. The guy at the laundry looked at me and said, “The president’s been shot.” That’s all, nothing more, not, “in Dallas,” or anything, just “the president’s been shot.” I didn’t disbelieve him, but god, what was he talking about? That doesn’t happen.

I went back to my dorm and someone had a radio going and a bunch of us sat around and listened to the reports from Dallas – I can’t remember who the newscaster was – we sat there in someone’s room and just listened to the slow death, really, of Kennedy.

Nobody had anything to say. When his death was finally confirmed, we went to the dining commons for lunch and – I have such a clear memory of this – the whole room was totally silent. Nobody was talking, total silence. The whole campus was in shock.

As I look back on it now, that’s what strikes me: total silence, no emotional display, nothing, just emptiness.

Sad time, my friend.

CAROLYN CONLEY, PhD, is a longtime Tulsan and career educator. She currently teaches at Tulsa Community College. She and husband Gary maintain their home in Tulsa:

I was in Coach Shell’s American history class my sophomore year at Webster, when he assigned us to write campaign speeches for our favorite presidential candidates. I spent hours [more time than I’d ever spent on any homework up to that date] crafting my speech for JFK.

Perhaps because mine was the only one in support of JFK in all of his classes, I was chosen to present my campaign speech at an all-school assembly.

I dressed for the occasion and boldly addressed the assembly, expecting a modicum of support, but only a few, polite hands met audibly and I left the stage while the Baptists cheered loudly as the Nixon speech-giver went to the podium. I don’t remember the person, but I remember that the Nixon speech was weak and pitiful. No matter, he was given a standing ovation and he took a deep bow.

I remember thinking, “How did I ever get to Red Fork, Oklahoma?” “Who are these people?” “Does any one think for themselves?”

I was indeed a stranger in a strange land. My political reasoning was shallow, to say the least, but in my gut I never trusted Richard Nixon.

During the campaign, I heard all the same “junk” about the Pope and the Catholics, but even at 15, I could not believe that Catholics, who worshiped the same God, could be the downfall of our country. Thankfully, neither did my parents. [They even attended the JFK Inauguration.]

Fast forward to 12:45 p.m. CST, Nov. 22, 1963 in Oklahoma City,

OK at Mercy Hospital School of Nursing, 519 NW 12th St.

I was in anatomy and physiology class taught by a female professor from the deep South whose pronunciation of medical terminology has forever tainted mine, when the antiquated intercom system buzzed.

We stopped everything and heard the words, “Students and faculty, please report to the chapel immediately. President Kennedy has been shot.”

The chapel was full of students, teachers, nurses, nuns, and priests at 1 p.m. when the announcement was made that President Kennedy was dead.

After what seemed like hours on my knees, I quietly left the chapel and took the stairs to my [shared] dorm room. Without thought, I entered my tiny, clothes closet and shut the door. There I cried for JFK and for me.

I felt alone, confused, forlorn, and uncomfortable, but in that closet I vowed to never allow the events of the world to spoil my vision of what could be.

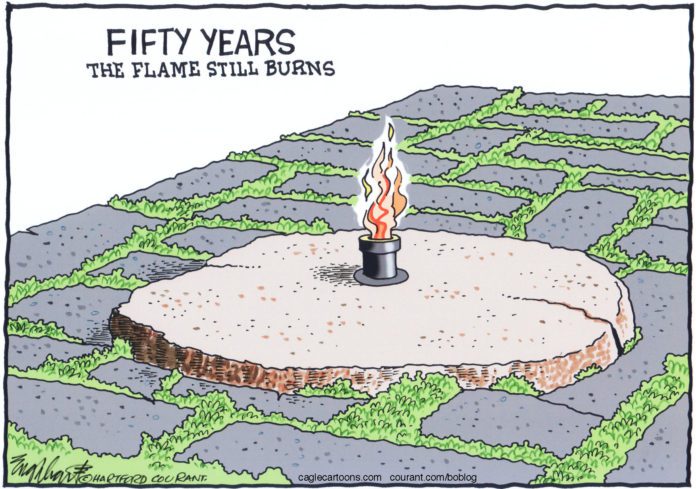

I have never given up this dream. As Teddy Kennedy said, “The work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.”

A final note: We, the Kennedy generation, may never know the full story of the events of that November day 50 years ago, but truth does have a way of overtaking myth, even if it takes a couple of generations.

I later became a Texas reporter and writer. As with many Texas journalists, I have been privileged to hear the true story of the president’s death.

The problem is, none of us have heard the same story.

I heard the story from Gen. Alberto del Rio Chaviano, last commanding general of the Cuban army before Fidel Castro entered Havana. In fact, Chaviano had once captured Castro after the rebel raid on the Moncada barracks in the early days of the revolution.

Did the general, whom I had come to know, believe what he was telling me?

I believe he did.

It was an interesting story to say the least.

Alas, none of it could be verified.

The general is gone. His story lies in the dustbin of history with all the other stories.

But, someday …

– Richard L. Fricker lives in Tulsa, OK and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. His latest book, The Last Day of the War, is available at https://www.createspace.com/3804081 or at www.richardfricker.com.