BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

It’s hard not to sympathize with Austin Holland.

In June, the former head of the Oklahoma Geological Survey announced his departure for bluer waters. His stated reason was that he was tired of working 80 hours a week, and wanted to spend time with his family. It also couldn’t have helped that the OGS has about half the staff it needs to do its job. And that’s not to mention that Mr. Holland recently began to suffer pretty intense political backlash for simply doing his job.

With that vast array of obstacles and disincentives, who could blame him for leaving?

Overworked, under-resourced, and attacked for doing the best you know how. Not many of us would stay around at a job like that. And nearly all of us would scoff at the notion that leaving just shows that we weren’t committed enough, or that asking for more means that we don’t care.

Certainly, it would be almost crazy for him to stay given those circumstances. And yet here we sit, scratching our heads over why we have a hard time keeping teachers in the state.

As Dean Lawrence Baines of OU’s Jeannine Rainbolt College of Education [full disclosure, JRCOE is one of my almae matres] recently pointed out, teachers routinely spend 50-60 hours a week on the job, not including the mounds of work they take home with them every evening.

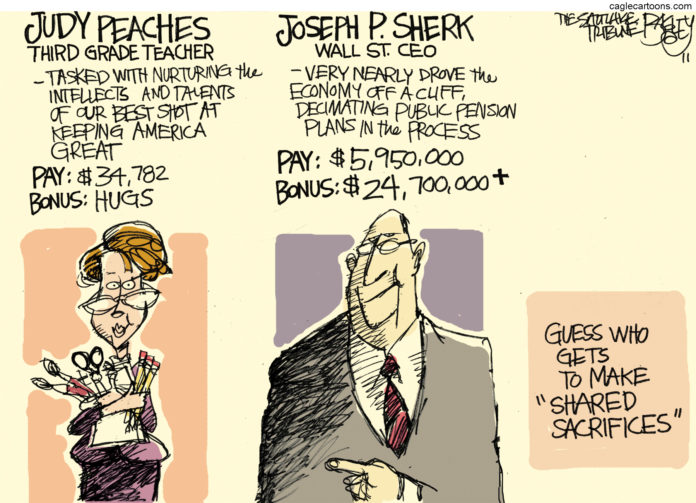

Despite this, teachers in Oklahoma can expect a starting salary somewhere in the low $30,000 range, even if they’re coming in with an advanced degree.

Fortunately for them, their low salary means their kids will at least qualify for reduced-price school lunches. And, of course, they can always make up the difference by taking one of those “we’re perfectly fine with you only working for two months in the summer” jobs that we all know are in such abundance.

In addition to being massively overworked and intentionally under-resourced, our teachers also have the privilege of working in one of those few fields where having gone through the system as a child makes you a policy expert.

It’s similar to the way that taking your car to the shop qualifies you to be a mechanical engineer. This authorizes policymakers and other public commentators to insist that our teachers be treated with the deepest suspicion and, of course, generally blamed for any student failure.

Should they be so irresponsible as to quit their jobs, or move to another place that pays them enough to support their families, it’s little more than evidence that they aren’t sufficiently committed to their work or to Oklahoma.

And of course, how dare they be so presumptuous to ask for more … Don’t they care about the children?!?

I think it’s safe to say that, just like with Mr. Holland, few of us would put up with what we put our teachers through. And there’s little mystery about what we need to do to retain more high quality teachers in Oklahoma.

First, we need to stop treating them like children and instead treat them like the highly trained professionals they are. Our policy makers need to spend more time figuring out how to sufficiently fund our schools, and less time trying to devise schemes to interfere with the implementation of what educators know are the best practices in their fields. Surely there are ineffective teachers and administrators in the system, but to allow a handful of incompetents to throw an entire field into suspicion is as silly as it is disrespectful.

Secondly, we simply need to pay teachers more. Teacher pay, perhaps better than any other example, belies the belief that salaries are proportional to a job’s importance. Education is perhaps the most important social function of the state, and it is utterly embarrassing that we reward it so meagerly.

Of course, this will mean more funding for education, which is tricky to do when your elected leaders are intentionally bankrupting the state. [That’s a little harsh, but I don’t know how else to characterize a situation where they looked at a budget deficit and said “Let’s fix it by cutting revenues!” And so, instead, in an effort to make-due, we’re seeing reductions in hours.

Dean Baines’ suggestion that teachers be given a humane and completely normal lunch break aside, we’ve instead started to experiment with shortening the school week. So the logic goes if we can’t afford to educate them for five days a week, let’s shoot for four.

From a purely budget perspective that may make a lot of sense. And so far, in the few districts that have tried it, it hasn’t seemed to cause any tremendous problem, at least for those families that can afford childcare arrangements. But we have to ask ourselves what message a shorter week sends to our children?

Anyone who has ever worked in education or has kids in school can tell you that kids learn much more in a school day than the material we try to teach them. They learn lessons from the way their teachers react to kids of different races or social class, they learn lessons about our priorities from the order things get fixed in the building, and they learn things from the structure of the school day.

Educational theorists call this “the hidden curriculum,” and it is a part of education that everyone involved has to acknowledge if they hope to understand what’s actually going on in a classroom.

Cutting the school week teaches children a very clear lesson: education is of secondary importance to the other things that we have to do. And yet without a quality education, how can we hope that our children will be able to do the other things that we have to do, much less actually be well prepared to participate in our democratic institutions?

Teachers also receive plenty of hidden curriculum in their work day. Our ingratitude at their Herculean efforts, our unwillingness to provide them with that they need to do their jobs effectively, and our perpetual insistence that even those who are managing to be effective are suspect sends them an unequivocal message: we don’t really need you.

We should little wonder that so many of our best and brightest simply don’t hang around.

– Christiaan Mitchell is a lawyer who holds master’s degrees in philosophy and education. He lives in Bartlesville.