BY DAVID PERRYMAN

Sylvia Barrett, an idealistic first-year English teacher at inner-city Calvin Coolidge High School, set out to instill in her students an appreciation of Chaucer and all things classic until in her classroom she found broken windows, no chalk and nothing but promises that books will arrive … late.

Sylvia Barrett, an idealistic first-year English teacher at inner-city Calvin Coolidge High School, set out to instill in her students an appreciation of Chaucer and all things classic until in her classroom she found broken windows, no chalk and nothing but promises that books will arrive … late.

Ms. Barrett is the main character in Bel Kaufman’s bestselling 1965 book Up The Down Staircase, using memos, notes, letters and scraps of paper to expose the trials of a teacher. Student indifference, rules, lack of parental involvement, more rules, poor building maintenance and rules as far as the eye can see are some of the issues that jeopardize the future of career teachers.

Bel Kaufman was born in 1911 in Berlin and emigrated to the United States in 1923. Forty-nine years after she wrote her best-seller, Bel Kaufman is still living in New York and continues to write. Unfortunately, many of the issues that the 103-year-old author exposed a half century ago still exist and still impede our educational system.

What made her book a bestseller and the 1967 film of the same name so popular was another issue that still exists. Bel Kaufman gave us insight into the hearts of millions of teachers and why they continue to do what they do in the face of constant battering and adversity. They are special people who defy reason and accept low pay, long hours and a lack of respect.

The common thread is that teachers accept this challenge because they were once touched by a teacher. In Kaufman’s book, Sylvia considers quitting, but realizes in the end that she is indeed touching and bettering the lives of her students.

Sylvia encountered what society threw at her and because she was a teacher she remained faithful. We are to be thankful for thousands of teachers across Oklahoma who have the heart of Sylvia Barrett.

Answers are not simple. Today, Oklahoma’s attempt to establish a meaningful curriculum is at a crossroads. How we got here is often misunderstood.

By its very nature, education has two components, instruction and assessment.

While we rail about the federal government’s intrusion into curriculum [instruction] we should be more concerned about the role it plays in assessment [testing]. Until 2001, the federal government’s funding stream was pretty well limited to schools serving impoverished children pursuant to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Everything changed in 2001 when President George W. Bush signed the well-intentioned No Child Left Behind and pronounced that, “The fundamental principle of this bill is that every child can learn, we expect every child to learn, and you must show us whether or not every child is learning.”

NCLB provided that if schools didn’t improve, they faced significant consequences and could be shut down with teachers and administrators replaced. U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said it was harmful and “led to a dummying down of standards, led to too much of a focus just on a single test score.”

Unfortunately, No Child Left Behind is still the law and it will likely remain so as long as partisan gridlock in Washington cannot agree upon the color of the sky.

So rather than replace NCLB, the Department of Education issues waivers and awards funding based on incentivizing the same principles of NCLB. One form of incentive is called Race To The Top and funds those states that establish and maintain high academic standards while states that do not simply … did not.

Priority Academic Student Skills [PASS skills] used in Oklahoma and other states were universally considered insufficient to compete for Race to the Top funding. In response, the National Governors Association used private foundation money to develop Common Core as adopted by Oklahoma and 44 other states.

Oklahoma therefore enjoyed a NCLB waiver and Race To The Top funds. Lost in the concept is that while the Common Core curriculum was not federally developed, the federal government did spend about $350 million developing the test that is to be used to evaluate performance.

Therein lies the problem. Oklahoma’s children need to know that two buffalo plus two buffalo equals four buffalo and young Texans better reach the same numerical conclusion even though they may choose to count longhorns in the Lone Star State while Arkansans may count razorbacks and our neighbors to the north may use Sunflowers as the object of their math problems. Such goes curriculum.

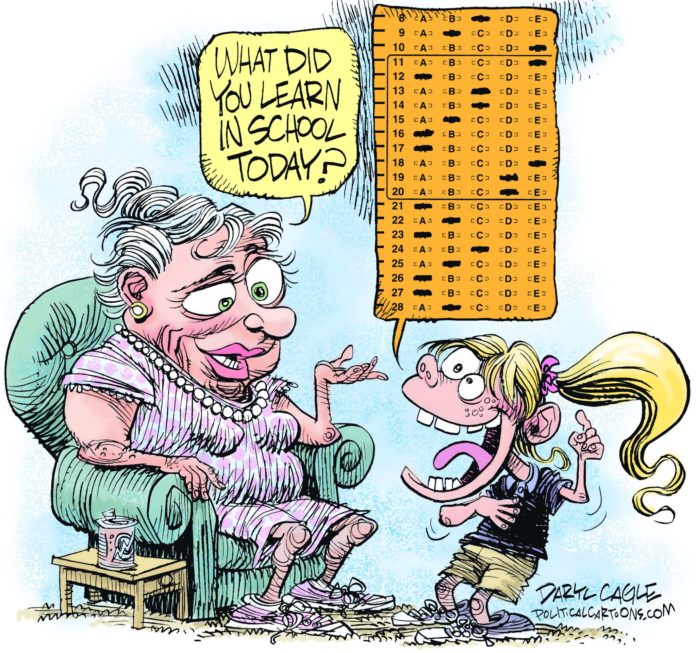

But when high stakes test scores are the basis for advancement, salary adjustment and all things important, it really doesn’t matter what the curriculum says. Teaching to the test becomes the means to success and that problem will continue so long as NCLB remains the law.

It is Up The Down Staircase all over again.

– David Perryman, a Chickasha Democrat, represents District 56 in the Oklahoma House of Representatives