One way of thinking about the good life is to focus on the question “What is the goal of human life or what is the end or aim that we as humans should be pursuing? Philosophers who use this question as their primary approach to understanding the good life are called teleological ethicists.

One way of thinking about the good life is to focus on the question “What is the goal of human life or what is the end or aim that we as humans should be pursuing? Philosophers who use this question as their primary approach to understanding the good life are called teleological ethicists.

The most well known philosopher who used this teleological approach was the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle who understood the “telos” or goal of human life to be what he called Eudaimonia, which is best translated as “human flourishing.”

For Aristotle, Eudaimonia is the telos or goal of every human being, and it is attained by using our reason in the best way we possibly can to cultivate our moral and intellectual virtues as a means for living the good life as persons within a community of other persons. Aristotle believed that education is required for the cultivation of these virtues, and he thought this education included the cultivation of virtues through the practice of good habits of human living.

Virtues are created through good habits, while vices are created through bad habits. Aristotle believed that good habits, or virtues, help develop a state of the soul that leads to a life of moderation between the excesses and deficiencies of bad habits, or vices. Virtues are the mean between the extremes of the vices.

To achieve personal human flourishing, Aristotle believed that we should use our highest function as well as we possibly can, and he believed that our highest function is reason.

The good life consists of a life of study with a few good and virtuous friends in which we learn to reason as well we possibly can and in which we allow our reason to rule over lower aspects of our being, such as our appetites, desires, and feelings. The good life is a life in which we develop moral and intellectual virtues.

When reason rules over the lower aspects of our being, or what Aristotle saw as the lower aspects of our soul, the result is the creation of moral virtues. When we live a life of study and cultivate the best functioning of our rational abilities, the result is the development of intellectual virtues, which is basically the ability to reason well. Aristotle believed that the development and expression of both moral and intellectual virtues are necessary for true human flourishing to be experienced.

Aristotle believed that humans are not isolated individuals, but rather we are social animals who require relationships with other human beings to flourish. No person is an island, and no one can be fully happy if they lack genuine and virtuous contact with other persons. Social flourishing in the good society consists of practicing the whole of virtue in relation to all other members of the human community and working together to establish justice and harmony in the good city or the good society.

If we are virtuous in our relations with each other, we contribute to the creation of a virtuous, good, and just human community.

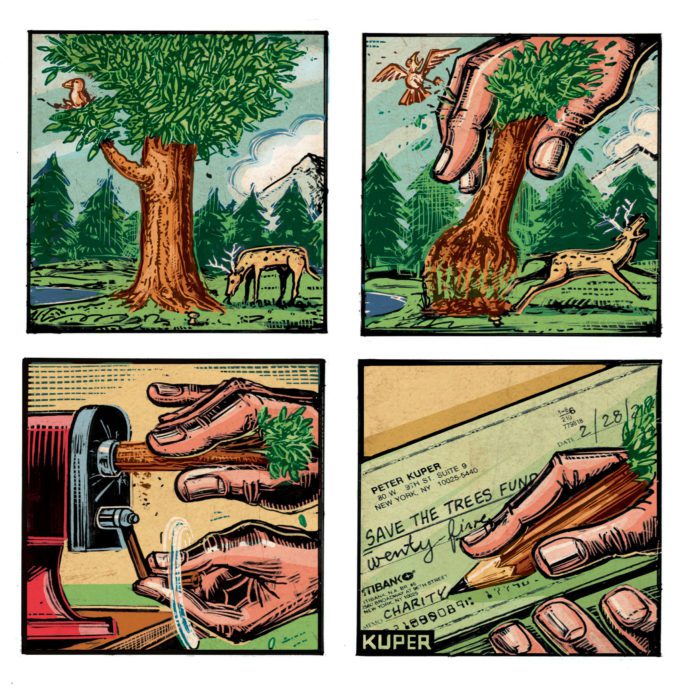

Today we see more than ever before that human flourishing is not only the flourishing of human persons in human community, it is also the flourishing of human persons within the larger ecological community. We know that human persons cannot flourish for long unless the ecological community of which we are all a part is also flourishing.

So in addition to the personal and social flourishing that Aristotle sees as essential to eudaimonia, it is important for a teleological approach that is relevant for our time to include the necessity of ecological flourishing for we as humans are always persons-in-ecological-community.

If human flourishing within the context of a flourishing ecological community is seen as the goal of human life, then it is imperative [a moral responsibility even] for the human community to address the global challenges of peace, poverty, social justice, and sustainability that directly affect human flourishing within our ecological community.

These challenges are not peripheral to the good life; they are at the very core of what promotes human flourishing. Addressing these challenges is at the very core of that which contributes to the good society within the broader ecological community.

The crises of violence, injustice, poverty, and ecological devastation in our world require an urgent response from all persons, institutions, and systems of the human community.

The current ways that human communities are living in the world are not sustainable, and it is our common task to contribute to finding sustainable ways of flourishing with each other within our ecological community. To borrow from Martin Luther King, Jr., the “urgency of now” has never been greater.

Each day, year, and decade that passes without systemic change in the human community contributes to less peace, less justice, and less flourishing for present and future generations of all life.

The reality of climate change and its effects on the ecological community make the need for systemic change the greatest moral challenge in human history, for we are affecting the very context in which any flourishing is even possible.

Perhaps we all have something to learn from Aristotle as we attempt to develop good habits that will contribute to the virtues necessary for personal, social, and ecological flourishing, but I think that today the practice of good habits is not only about cultivating moral and intellectual virtues; it must also be about cultivating the ecological virtues necessary to live sustainably so that future generations of all life might simply live.

So let’s work together with some good friends to practice some good ecological habits for the cultivation of ecological virtue in ourselves and our communities. Let’s make it a habit to reduce, re-use, and recycle. Let’s make it a habit to walk, bike, and use mass transportation when we can. Let’s make it a habit to use video conferencing to cut down on our need to burn fossil fuels in flying and driving. Let’s make it habit to get our hands in soil, compost, and grow some of our own food; and let’s make it a habit to get as much of the rest of our food from local and organic sources. Let’s make it a habit to use renewable and clean sources of energy. Let’s make it a habit to march for ecological justice and become politically engaged in the work of systemic change for ecological flourishing. Over time by practicing these good ecological habits, we just might cultivate the ecological virtues within our souls that are necessary to bring a new age of ecological justice for this good earth that is our only home.

May it be so.