The vision of all educational institutions should be the cultivation of human and ecological flourishing, and their mission should be to educate humanity to make this vision a reality. The long-term value of education is minuscule if it does not contribute in some way to maintaining a livable climate and halting the global loss of biodiversity. Human flourishing over the long run is simply not possible without ecological flourishing.

When we begin to see education as a way to contribute more fully to the common good of all humanity and to the well-being of the whole earth rather than simply as way to get ahead, then we may have a chance to reverse our current descent into mass extinction and climate chaos.

The cultivation of critical thinking is a key ingredient of a vibrant democracy.

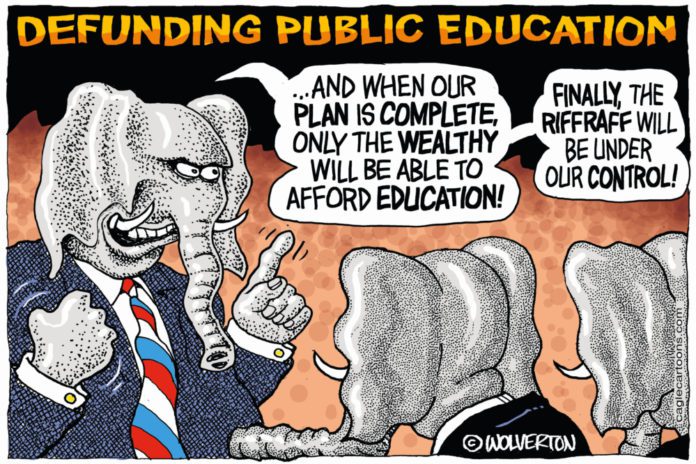

Anti-democratic propaganda thrives in a context where persons lack critical thinking skills, and critical thinking skills are lacking in countries that do not have strong public education systems. Here in the United States, a significant portion of our current political crisis is connected to our deficit in critical thinking.

A vibrant democracy requires a strong public education system. The most robust democracies in the world have the best systems of public education. It is no accident that as public education has been systematically weakened in the United States that our ranking in the Democracy Index has fallen precipitously and that we are now considered a flawed democracy rather than a full democracy.

Imagine if we could make a shift in our thinking and we started telling our children that we want them to have a good education so that they can help us create a more loving, more just, and more sustainable world. That would be a vast improvement over our current focus on pursuing education as something to do simply to get a job and be successful.

Perhaps we could embrace together that the primary goal of education in the Beloved Community is service, not success. We seek education not to conquer the world as we climb the ladder of success, but to save the world as we give of ourselves in service. Such a vision of education for the common good might radically change the way we view education and help us prioritize access to and affordability of quality education for all persons.

The societal benefits of providing tuition free college and vocational education in the United States would far outweigh the costs and allow persons to enter their careers and service to society without a crushing load of student debt that harms them and their families and perpetuates inequality of opportunity and wealth inequality.

If we understood the education of all persons as a societal good rather than only as a good for individuals, then we would bear the burden of the costs of education together as a society rather than placing the brunt of that burden on the individual persons being educated.

Perhaps if we saw education as being for the common good, we could more clearly see what it is that is hindering our society from truly flourishing.

Perhaps we could recognize that the worsening of wealth inequality and the systems that perpetuate it are at the root of our real problems as a society and that all of the culture wars are a manufactured smokescreen to keep us from seeing and addressing this.

Perhaps a vision of education for the common good would help us begin to see that the way we fund and operate K-12 public education, vocational and technical education, and higher education is currently exacerbating the problem of wealth inequality rather than reducing it.

Education should be the most positive force for advancing equality of opportunity in a society, but we have made lack of access to affordable and quality education to be one of the greatest barriers to opportunity and a driving force of worsening wealth inequality in our nation.

This is even more greatly exacerbated by the fact that schools in areas of greater poverty are more poorly funded owing to the use of property taxes to fund such a significant portion of public education. Wealthy areas with higher property taxes get more funding for public education, thus perpetuating a vicious cycle that widens the wealth gap and the opportunity gap between the rich and the poor.

To make matters worse, our investments in public higher education have been gutted by tax cuts for the wealthy as we have moved away from a progressive tax system to a system that is much more regressive in nature. Truly public higher education is almost nonexistent in the United States now with the vast majority of the costs being covered by increased tuition and fees coming directly from the students and their families. The only persons who are able to come out of college debt free are the wealthy or those with significant scholarship support, while the majority take on a significant amount of debt that often takes decades to repay.

It is not an accident that the wealth gap in the United States was decreasing and the economy was lifting so many persons out of poverty in the post-World War II period until the late 1970s. This was the period in which our nation invested heavily in the mental and physical infrastructure of our society through a system of progressive taxation.

Part of this investment included maintaining one of the best public education systems in the world at the time, publicly funding a much higher percentage of the costs of higher education than we do today, and paying for the education and vocational training of millions of veterans. Education was one of the keys to the economic prosperity of that time.

Sadly, since the early 1980s, we have made a shift away from progressive taxation and we embraced a trickle-down economic theory based on a warped individualistic view of humanity that enriches a small percentage of the population at the expense of the common good.

As a result, our system of education that was once the envy of the world was quickly reduced to mediocrity. A vision of education for the common good was lost to the individualistic emphasis of the “me first” generation of the 1980s that continues to persist to this day.

As our education system declined, it is not a surprise that numerous less individualistic social democracies around the world would surpass us in their educational outcomes, and it is also not surprising that those same better educated countries have surpassed us in overall health, life expectancy, happiness, and quality of life.

It is not a surprise that the social democracies that continue to hold the vision of education for the common good are less divided, less corrupt, and have much more vibrant and participatory democracies than we do.

These better educated social democracies are also much more effective at caring for the earth and being ecologically sustainable, and they are leading the way in protecting a livable climate for generations to come.

While it may be true that we Americans have a hard time admitting when we are wrong, perhaps the time has come for us to recognize that our current individualistic and capitalistic approach to education is not working for us. It is making us worse as a nation by almost every measure, and it is one of the many factors that are literally tearing apart our social fabric and thus tearing us apart from each other.

The path toward beloved community is long and difficult, but we will surely never get there unless we begin to recognize that education for the common good is good for us all.

Editor’s Note: This essay originally was presented as a discourse at Red River Unitarian Universalist Church in Denison, TX

Wow! When was the last time I thought about Josiah Royce?

The goal is admirable, of course, and the evidence overwhelming. But, maybe an aside on educating people to be more well-rounded, capable of enjoying more of life’s offerings would appeal to their selfishness. More, more, more — and in that ideal community even more to share.