BY JOE CONASON

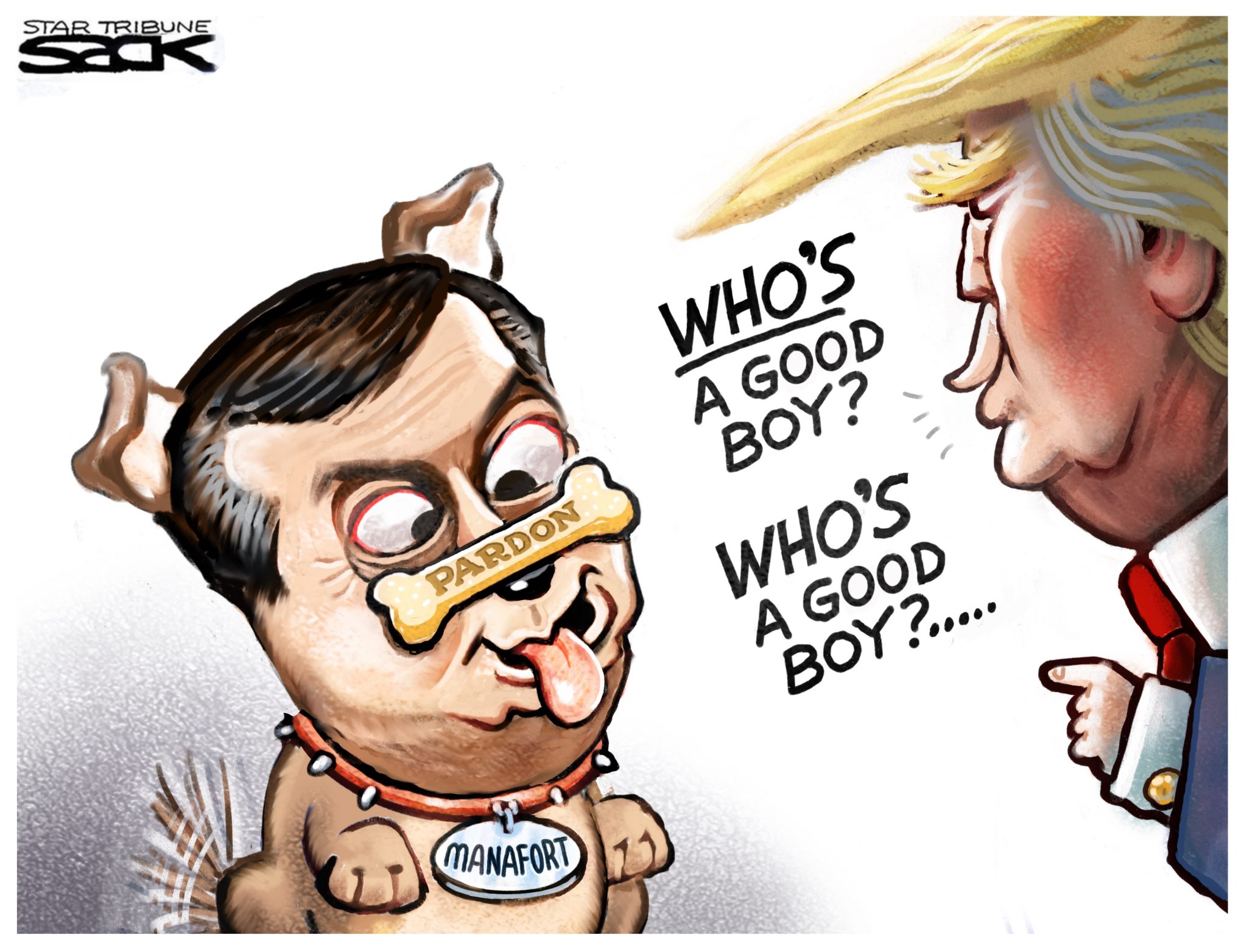

For more than a year, Donald Trump has dangled presidential pardons before former associates who might provide evidence against him. He teased such miscreants as Mike Flynn, his crooked national security adviser, and Michael Cohen, his bullying ex-lawyer. And now we know how blatantly he has been using that same enticement to lure his former campaign manager Paul Manafort to abandon a plea agreement with the special counsel.

For more than a year, Donald Trump has dangled presidential pardons before former associates who might provide evidence against him. He teased such miscreants as Mike Flynn, his crooked national security adviser, and Michael Cohen, his bullying ex-lawyer. And now we know how blatantly he has been using that same enticement to lure his former campaign manager Paul Manafort to abandon a plea agreement with the special counsel.

While supposedly cooperating with Robert Mueller’s prosecution team, Manafort and his attorney were revealing to President Trump and his lawyers what questions the prosecutors were asking and how he had answered. In short, he acted as a spy for the White House.

Why would a man facing many years in prison accept such a grave risk during those months of conferring with the Trump lawyers unless he heard a powerful hint of a pardon?

Now there is much more than a hint. So reckless is Trump that he publicly admits he may grant a pardon to Manafort, who was convicted of serious felonies and undoubtedly committed more. It is not “off the table,” Trump said on Wednesday.

Pardoning Manafort under these circumstances would be the most blatant abuse of that constitutional power by any president in history – and the most obvious White House obstruction of justice since Nixon’s minions gave suitcases of cash to the Watergate burglars. It would be an impeachable offense, especially when combined with Trump’s other overt acts of obstruction, starting with his firing of FBI Director James Comey.

But even if the craven Senate Republicans were to allow Trump to escape an impeachment conviction, he could be prosecuted for obstruction and misusing the pardon power after leaving office. While he may be constitutionally immune from prosecution now, a suspicious pardon would render him vulnerable to indictment as soon as his presidency would end.

His own lawyers should warn him how dangerous such a corrupt act would be. And if he doesn’t believe them, he can ask former President Bill Clinton, James Comey or former Attorney General Jeff Sessions about the pardon of businessman Marc Rich in January 2001.

There was nothing corrupt about the pardon of the “fugitive financier,” signed by President Clinton on his final day in office. Yet even some of Clinton’s friends and allies – and all his critics in the media and Congress – suspected he had pardoned Rich in return for millions of dollars in campaign and foundation contributions from Rich’s ex-wife, Denise Rich.

Actually, Clinton pardoned Rich after then-Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak requested that favor three times during their protracted Mideast peace talks with the Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat. While Clinton never blamed Barak for the trouble caused by the controversial pardon, it is clear that he acted out of gratitude for the sacrifices Barak had made in search of peace [which almost immediately led to the Israeli’s electoral defeat].

The trouble began instantly. Enraged by the Rich pardon, which she deemed an insult to her own prosecutors, then-U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White swiftly opened a criminal investigation of the former president who had appointed her. Her headline announcement devastated Clinton and delighted his enemies. On ABC News, a Republican member of the Senate Judiciary Committee eagerly explained how and why Clinton could be prosecuted despite the absolute nature of the pardon power.

“[I]f a person takes a thing of value for himself or for another person that influences their decision in a matter of their official capacity,” said a smirking Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-AL, “then that could be a criminal offense.” No doubt Sessions could explain to Trump how that theory of official corruption would apply to the pardon of Manafort – or any other favor granted to conceal the truth from the special counsel.

Whatever the prosecutors in the Southern District of New York thought of Clinton’s fervent denials, they continued to investigate him, as well as Denise Rich and other donors to The Clinton Foundation, for more than three years. Almost nobody was paying attention by the time the pardon probe officially concluded – without any wrongdoing discovered. The end was quietly announced by the new U.S. attorney, an appointee of then-President George W. Bush named James Comey. Naturally, that announcement got almost zero news coverage, because American media is rarely keen to report facts that exonerate the Clintons.

Federal prosecutors could make no case against Clinton because there was no case to be made. But the bipartisan principle, derived from our system of equal justice, remains valid: A corrupt pardon issued by a former president is fair game for criminal prosecution. And Trump will flout that principle at his own peril.

– Joe Conason’s columns appear regularly in The Oklahoma Observer

Creators.com