BY JOHN THOMPSON

The Tulsa World’s headline nailed the big picture, Staggering: 30,000 Oklahoma Teachers Have Left Profession in the Past Six Years, Report Shows. The World’s Michael Dekker cites state Superintendent Joy Hofmeister who explained, “The loss of 30,000 educators over the past six years is staggering – and proof that our schools must have the resources to support a growing number of students with an increasing number of needs.”

The Tulsa World’s headline nailed the big picture, Staggering: 30,000 Oklahoma Teachers Have Left Profession in the Past Six Years, Report Shows. The World’s Michael Dekker cites state Superintendent Joy Hofmeister who explained, “The loss of 30,000 educators over the past six years is staggering – and proof that our schools must have the resources to support a growing number of students with an increasing number of needs.”

These huge losses occurred in a state that employed only 50,598 teachers in 2017-18.

Hofmeister addressed the immediate problem: “Steep budget cuts over the last decade have made the teaching profession in Oklahoma less attractive, resulting in a severe teacher shortage crisis and negative consequences for our schoolchildren.” The analysis – 2018 Oklahoma Educator Supply and Demand Report– by Naneida Lazarte Alcala, also touched on the ways that the lack of respect and the decline of teachers’ professional autonomy contributed to the massive exodus from the classroom.

The report showed that Oklahoma’s annual attrition rate has been 10% during the last six years, which was 30% more than the national average. This prompted an increase from 32 emergency certifications in 2012 to 2,915 in 2018-19. As a result, the median experience of state teachers declined by one-fifth in this short period.

Given the challenges faced by the Oklahoma City Public School System, it is noteworthy that the highest turnover rate in 2017-18 [almost 25%] occurred in central Oklahoma. Over 11% of teachers in the central region are new hires.

It should also be noted that charter schools have the highest turnover rate [almost 42%], even higher than that of middle schools.

I kid my colleagues in middle school. But there is a serious point. Choice advocates have had success in their political campaign to defeat traditional public schools, but their turnover rate is another sign that the oversupply of charters shows that privatization isn’t a viable, educational alternative to neighborhood schools.

But the financial cutbacks were not the only cause of the crisis. Alcala cites a survey of teachers who have left Oklahoma schools; two-thirds said that increased compensation would not be enough to bring them back to the classroom. Citing reasons that were beyond the scope of the report, 78% said that the quality of the work environment had declined, and nearly half said it had deteriorated a great deal.

On the other hand, the report suggested aspects of teaching conditions that merit further examination. It cited research on the negative effects of teacher turnover on student achievement, especially for low-income students. This stands in contrast with research cited by accountability-driven, competition-driven school reformers who argue that turnover isn’t necessarily bad. After all, they invested heavily in trying to identify and dismiss low-performing teachers.

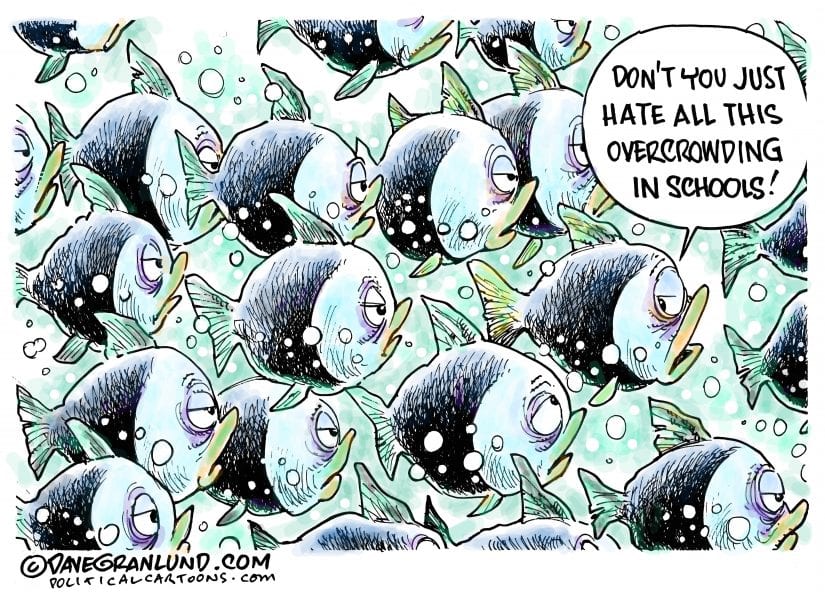

The SDE study cited the value of low student-teacher ratios in terms of raising student achievement, especially for low-income students. It also noted the national pattern where education degrees have “notoriously” declined, as well as the drop in graduates in Oklahoma teacher preparation programs.

And that brings us to the unintended results of features, as opposed to bugs, in the corporate school reform movement that peaked during this era.

Reformers who lacked knowledge of realities in schools misinterpreted research on California schools which supposedly said that class size reductions don’t work, and then ignored the preponderance of evidence on why class size matters. Reformers often blamed university education departments for poor student test scores, and experimented with teacher preparation shortcuts. Some reformers even said what many others felt about wanting to undermine the institution of career teaching.

To understand the decline of working conditions for teachers, the teacher strike in Denver, as well as those in Oklahoma and other states, must be considered. Colorado Sen. Michael Bennet, the former superintendent of the Denver schools, called for incentives in urban schools by 20-somethings who would work for seven to nine years. His hugely expensive and complicated incentive system provoked the recent strike.

It should have been obvious that teacher churn is bad for students, who need trusting relationships with educators who love them. A decade ago, however, edu-philanthropists and the federal government essentially imposed a rushed and risky experiment on schools in Oklahoma and across the nation. These non-educators praised the gambles as “disruptive innovation.” But they incentivized primitive teach-to-the-test malpractice and drove much of the joy of teaching and learning out of schools.

Evidence that excellent teachers were being “exited” by a flawed statistical model used in these teacher evaluation systems was ignored. Since these policies incentivized the removal of highly paid veteran teachers during the budget crisis prompted by the Great Recession, Baby Boomers were often targeted. This resulted in schools such as Upper Greystone, an elementary school with 24 certified staff, which had 21 teacher vacancies at the beginning of the 2014-15 school year.

During the 1990s, education experts frequently warned that Baby Boomers would soon be retiring, and sought ways for veteran teachers to pass on their wisdom. During the last decade, however, corporate reform made the staggeringly serious mistake of undermining teachers’ autonomy in order to force educators to comply with their technocratic mandates. Veteran teachers were rightly seen as opponents to their teach-to-the-test regimes, and often they were pushed out of the profession so they wouldn’t undercut the socializing of young teachers into opposing bubble-in accountability.

Even if we had not made another unforced error and dramatically cut education spending, failed reforms would have wasted educators’ time and energy, damaged teachers’ professionalism, and sucked much of the joy of teaching and learning out of classrooms. When the retirement and the pushing out of Baby Boomers, funding cuts, and drill-and-kill pedagogy came together during and after the Great Recession, this staggering exodus of teachers was triggered.

– John Thompson is an award-winning historian who became an inner-Oklahoma City teacher after the “Hoova” set of the Crips took over his neighborhood and he became attached to the kids in the drug houses. Now retired, he is the author of A Teacher’s Tale: Learning, Loving, and Listening to Our Kids.