BY SUSAN ESTRICH

I was blessed.

On my first day as his law clerk on the DC Circuit, Judge J. Skelly Wright, who had hired me sight unseen when I was elected president of the Harvard Law Review, told me that Justice Brennan would not do the same. True, he always hired Judge Wright’s Harvard clerk sight unseen, and he had never passed on a Harvard Law Review president. But they were all men. It was nothing personal, the judge informed me; he just didn’t hire women.

Which is how I came to be clerking for the Supreme Court’s most junior member, Justice John Paul Stevens, a Republican appointee whose confirmation was opposed by the National Organization for Women. As best I could tell, he had never had a woman clerk, either. But he didn’t care.

It was an experiment, he explained to me when I went on my interview. The other justices each had three or four clerks. But when he clerked for Justice Jackson, there were only two clerks, and since he did many of the first drafts himself [which no other justice did], he wanted to try it with two.

Was I game?

I figured it might be the only game I was asked to play.

I was game.

No one had done it since Justice Jackson, and no one has done it since. As it turned out, I think Jim and I were the luckiest clerks in a long line of very lucky young lawyers. We learned from the best. And the wisest. But we didn’t know it then, or at least I didn’t.

I had just spent a year with Judge Wright, rekindling all my liberal passions after two years trying to play it down the middle at the law review. The reason NOW opposed Justice Stevens was because of a “bad” opinion he’d written about married stewardesses. He was in favor of requiring minor girls to have parental consent to get an abortion. What if I had to work on opinions like that, for the United States Supreme Court, no less? How could I do my best job if it was my job to justify discrimination?

I needn’t have worried. I never did. Quite the contrary.

The Hyde Amendment, which provided that Medicaid would not pay for abortions for poor women unless their lives were endangered, was passed in 1976. It was on its way to the court. A district court in New York forbid enforcement of the limits. But in Illinois, the court below had upheld the law’s constitutionality. Absent a stay, poor women in Illinois would immediately lose access to abortions.

It was August. The petition for a stay went to Justice Stevens, because he was the justice who oversaw the 7th Circuit. I figured my new boss – he of parental consent – was probably one of those justices who never saw an abortion restriction he didn’t like, which is how abortion would be limited since Roe v. Wade was decided five years earlier. But I’d give it a try.

“I know where the court is headed [the first factor in granting a stay],” I said, “but considering the irreparable injury women may suffer if forced to resort to illegal abortions, given the much greater cost to the government of pregnancy, childbirth and welfare … ”

He stopped me. He had already decided.

There were at least two months before the court reconvened. We could protect poor women’s constitutional rights at least until October, so long as no other justice insisted on vacating the stay while on vacation.

Can you write an opinion that is long and complicated enough that nobody will want to deal with it this summer?

I could. He did.

It was as dense as any law review article you could write.

It was the only opinion like that we ever produced.

I learned how to write. No long sentences. No law review-ese. Short and clean. Tell the story. If you tell it right, you don’t need all the crutches like “therefore” when it isn’t, or all the in terrorem adjectives that we would see in some of the most expensive cert petitions and briefs. The higher the decibel level, the weaker the argument.

There was one more abortion case that term, Bellotti v. Baird. It was a parental consent case out of Massachusetts. The problem with parental consent is that many girls are rightly afraid to tell their parents that they are pregnant. In 1976, the court had held that an absolute requirement of parental consent was unconstitutional.

Roe v. Wade is grounded in the right to privacy, a right to make decisions on your own, the right. So Massachusetts decided to provide a judicial override: A girl who could not secure consent of both her parents could just go to her local court and ask a judge to decide.

Would Justice Stevens, who wrote separately in 1976 in support of parental consent, go along with the judicial override escape hatch?

He did not. How can you have a right to privacy that in many cases can only be exercised if the government grants you permission?

Justice Stevens wrote for the four pro-choice justices. Justice Brennan assigned him the opinion. Let the girls handle it, Brennan told him.

I was pretty sure he meant me. I took it as a compliment but one I didn’t deserve. It was Justice Stevens who taught me not only how to write but also how to think like a lawyer. In the 40 years since, I have never met a finer one.

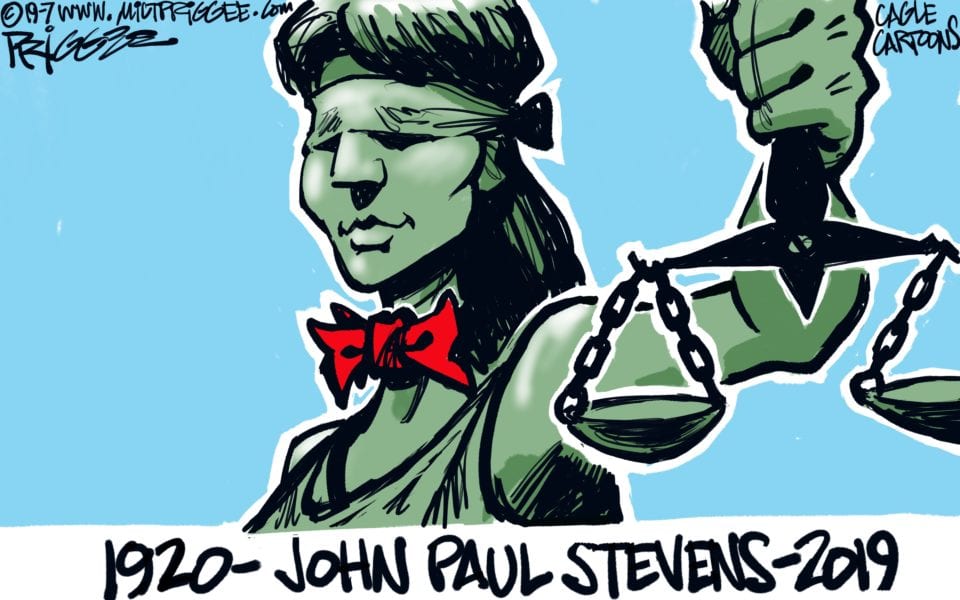

May he rest in peace.

Creators.com