About 40 years ago, a right-wing codger named Eddie Chiles became a momentary political celebrity in my state by buying airtime on hundreds of radio stations to broadcast his daily political rants. Having made a fortune in the Texas oil fields, he pitched himself as a rags-to-riches, self-made success story.

“I’m Mad Eddie,” as he was known, repeatedly proclaimed that he was “mad” about big government – particularly federal programs that taxed him to help poor people, who should help themselves by becoming oil entrepreneurs like him.

It’s simple, he instructed in the tagline to his tirades: “If you don’t own an oil well, get one.”

Well, maybe you can’t afford an oil well, but what if you could own something even bigger – an entire electric utility? What if you were to control an energy business that’s also an economic development engine and a grassroots force for advancing social justice? You wouldn’t own it all by yourself, but you would indeed be a full-fledged owner, with a voice on everything from hiring to setting rates, from green energy to community investment.

This empowering populist possibility has quietly existed for millions of Americans since 1937, when then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal helped people create a vast network of member-owned and member-run rural electric cooperatives, or RECs.

While the barons of corporate-owned utilities serviced densely populated, easy-to-wire cities, they ignored rural areas as unprofitable, leaving families, businesses, schools and communities literally in the dark. Co-op ownership offered a bridge across this rural gap in our country’s vital infrastructure – and the people rushed to cross it.

Before the New Deal, some 90% of farm families had no electricity. By 1953, just 16 years later, more than 90% of them were wired, opening rural America to a world of new economic, social and cultural opportunities.

Co-op electricity has transformed rural America, but the co-ops offer something even more electrifying: democratic power.

By law, every household that uses the electricity is a member and can vote for a board that has actual decision-making authority to control resources including cash flow, good jobs, a customer base, facilities and financial acumen.

Moreover, unlike the corporate ethic of shareholder supremacy [in which maximizing profits of investor elites reigns supreme], these decentralized, grassroots utilities were guided by an egalitarian ethic formulated in 1937: the seven Rochdale Principles of cooperative organization:

– Voluntary and open membership.

– Democratic member control.

Members’ economic participation.–

– Autonomy and independence.

– Education, training and information.

– Cooperation among cooperatives.

– Concern for community.

With such a potent combination of power and principles – later expanded to include anti-discrimination, financial fairness and other components – RECs can be a mighty force for helping rural Americans make broad-based social progress. Indeed, in the past 30 years, some RECs have formally expanded their official purpose from simply providing electricity to also investing in such community needs as solar power, high-speed internet and financing for conservation retrofits.

Despite the strength and popular appeal of the co-op approach, RECs in regions where they are large and numerous [the South, Midwest and Plains] have hardly been models of dynamic progress. Even when they face stagnant economies and widespread poverty, many co-ops charge exorbitant rates and cling to a toxic legacy of coal-fired power plants spewing pollutants.

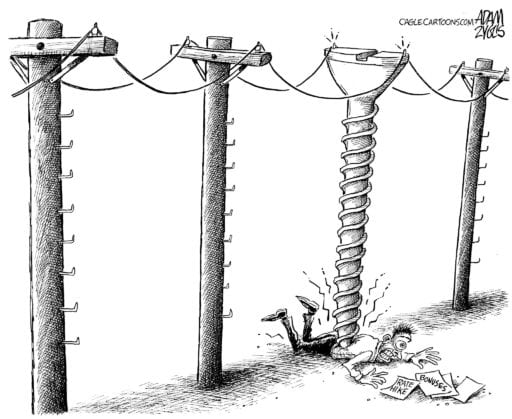

What happened? In effect, these co-ops got taken over by closed networks of entrenched rural power [bankers, real estate developers, ag-biz execs, old money families, trusted political retainers, et al]. These interests have steadily tightened their grip on these valuable utilities by using their financial power, social standing and legal cunning to dominate board elections.

Once in, these boards throw Rochdale principles out the window. Professional managers slide the decision-making and co-op books behind closed doors. In co-ops like these, the term “member” has effectively been shriveled to mean powerless consumer. Thus, shut out of the governing circle, members lose the will to participate, leaving the co-op a hollowed-out shell of its big democratic idea. A 2016 survey by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance found that 72% of America’s REC board directors were elected by less than 10% of members.

But as a co-op member, you do have a voice. The good folks at the New Economy Coalition recently released their Rural Electric Cooperative Toolkit with resources for member-owners seeking to reassert the democratic principles on which their co-ops were founded. The NEC works for an economy “that meets human needs, enhances the quality of life, and allows us to live in balance with nature.” Doesn’t that sound good? Check them out: neweconomy.net.