The new year has seen much wailing and gnashing of teeth in Oklahoma. On Jan. 3, 20-year-old college freshman Caleb Williams announced that he was entering the NCAA’s transfer portal, which could see the young quarterback leave the University of Oklahoma for greener pastures.

“Greener” is the optimum word here. After years as unpaid, indentured servants, college athletes have now been granted the right to benefit monetarily from their talents. Previously, only the institutions for which they worked were allowed to make money.

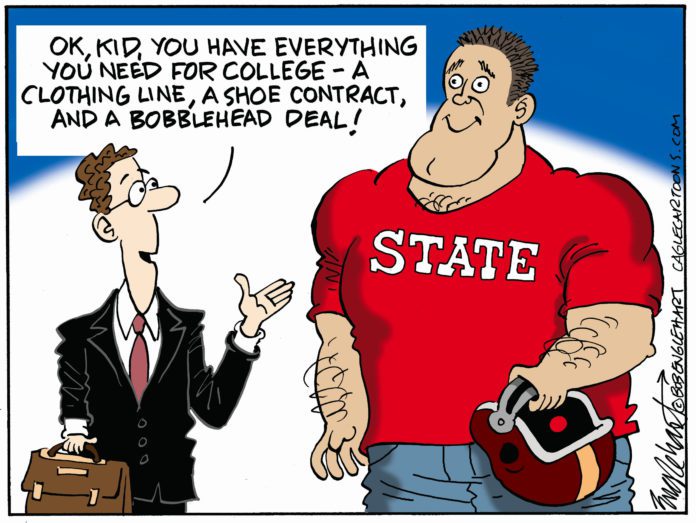

The new system is called NIL, since athletes can now be paid based on what the open market says their “name, image or likeness” is worth. It is only fair. The athletes are doing the work and providing the product at the base of lucrative TV contracts and university marketing arrangements.

Besides, if college art students can sell their work [I’ve bought some], and music majors can pick up some coin with regular gigs, and other students can be paid for work in their fields, it stands to reason that athletes should have the same rights.

And now they do.

One of the first and most ballyhooed examples was Quinn Ewers, a Texas high school quarterback, who skipped his senior year last year and signed a three-year, $1.4 million deal with a marketing company regarding his autograph as he enrolled at Ohio State University. He had other NIL deals as well.

Still only 18, and without a single college passing attempt, Ewers has now transferred to the University of Texas, where – as reported in Golf Digest, go figure – linemen “are poised to start making $50,000 per year via NIL benefits through a booster group called The Pancake Factory.”

Since many of those in the trenches, especially on offense, toil in obscurity, an outsider might not think their NILs have a high market value. But the boosters who have pooled their money to pay them realize the essential parts they play in any game.

Yep, where providing under-the-table payola once jeopardized an athletic program’s eligibility, blatant, publicized [for advertising purposes] pay-for play arrangements will now become crucial recruiting tools.

What will five-star recruit Ewers be worth?

What will a starting quarterback from a top college program be worth? Even if he couldn’t beat Baylor or Oklahoma State? Caleb Williams is about to find out.

In announcing his entrance into the transfer portal, Williams said, “I need to figure out what is the right path for me moving forward. According to NCAA rules, as a student-athlete, the only way I can speak with other schools and see who may offer the best preparation and development for my future career is by entering the portal. Staying at OU will definitely be an option.”

An option? Will he stay or will he go? His indecision torments many of the state’s sports talkers, who try to debate pros and cons of his options and downplay his culpability in putting OU into a situation reminiscent of Kevin Durant’s departure from the OKC Thunder.

Everyone thought Durant would re-sign. So, when he walked, the Thunder got nothing near his trade value. The longer Williams deliberates, the longer the limbo lasts for OU. The team could lose out on possible recruits or transfers who think they need to make up their minds sooner.

In an unprecedented move, OU Athletic Director Joe Castiglione and Head Coach Brent Venables issued a joint statement/sales pitch to try to keep Williams in the fold, pledging to “continue to be engaged with him and his family on a comprehensive plan for his development as a student and a quarterback, including a path to graduation and strategic leveraging of NIL opportunities.”

Does this continued engagement mean that OU will be given the opportunity to beat any NIL offers that float Williams’ way? Will there be a back-and-forth bidding war? An auction?

The OU statement also cited “OU’s commitment to student-athlete development and its powerful track record of preparing players for the next level, including quarterbacks for the NFL, is unparalleled. Jeff Lebby is one of the most elite offensive coordinators and quarterback developers in the country.”

It is a tough spot for pundits. They have to point out the implications of Williams’ decision-making delay without inadvertently offending this fine young man from a fine family to the point that they might be blamed for hastening his departure. Sooner Nation would not be pleased.

The Williams scenario at OU is being played out in varying degrees on campuses throughout the country. The combination of automatic eligibility through the transfer portal and dangling NIL money has made college football a true minor league operation, the shamateurism of the past replaced by out-and-out professionalism.

And the schools have only themselves to blame. By refusing to share their income with their workers, they saw said worker/athletes arrive at compensation by a route outside institutional controls.

They have sown the blowhard wind of faux amateurism. They are now reaping the whirlwind of athletic chaos.

We cannot be certain whether university greed or incompetence was at the heart of the stinginess.

In a 2020 article which he updated last week for Best Colleges, Mark J. Drozdowski addresses the question: “Do colleges make money from athletics?”

They undoubtedly earn money, but do they make profits?

He cites 2018-19 statistics that show Texas raking in $223,879,781 that year, followed by Texas A&M with $212,748,002. Your usual suspect are in the top 20: Ohio State, Michigan, Penn State, Alabama, Florida, LSU. Yeah, the big boys. OU ranked eighth at that time, with an athletic department income of $163,126,695.

But Dr. Drozdowski points out what I have been aware of for about 30 years, “that despite the huge sums of cash seen here, only a handful of schools actually make money through college athletics.”

At the time there were 65 Power Five conference schools. [Recent conference reshuffling has seen a few more schools move into that category.] But – among the public institutions that have to report on their finances – only 25 “recorded a positive net generated revenue in 2019.”

Those 25 posted “a net median profit” of $7.9 million. The other 40 reported “a negative net revenue” of $15.9 million.

No one in the next echelon, the so-called Group of Five – American Athletic, Conference USA, the MAC, Mountain West and Sun Belt. “All 64 of these institutions lost money in 2019, with a median deficit of $23 million per school.”

Drop down to the 125 FCS schools, which actually play for an expanded football championship, and you find all of them in the red, with a median loss of $14.3 million.

The 97 Division I schools without football posted a median loss of $14.4 million.

So, Dr. Drozdowski reports: “[O]nly 25 of the approximately 1,100 schools across 102 conferences in the NCAA made money on college sports” in 2019.

So, we can speculate that the college’s refusal to compensate their workers was partially due to the financial mismanagement of their athletic departments.

He and others cite the burden that high revenue sports such as football and basketball carry to support less lucrative sports.

Dr. Drozdowski’s findings do not surprise me. Almost 30 years ago, I found similar results when promoting the notion that my hometown Sam Houston State Bearcats and my alma mater Stephens F. Austin Lumberjacks should de-emphasize athletic spending in favor of academics.

[At that time, only 18% of NCAA athletic department expenditures were earmarked for scholarships.]

I was ignored, of course, as the schools moved up the conference hierarchy ladder – evidently with athletic department deficits all the way – culminating now with SHSU shucking its Piney Woods rival to join Conference USA. SFA stays in the Western Athletic Conference, which bears no resemblance to the WAC I grew up with.

I am not anti-athletic. As I wrote in 1993, “I love sports. I played as long as my limited abilities allowed – never learning to hit an overhand curve and disproving the theory that small guys are fast. I own an SFA Intramural Champion T-shirt; I wish it still fit.” Amen!

My best pals in my small town schools were fellow athletes. I could – and try to – fill columns with arcane baseball facts. The drive to become a newspaperman was fueled by my love of sports and the great sportswriters at Sports Illustrated in the 1960s.

My objection to the over-emphasis on college sports back then was that those deficits were being offset by “student fee” money siphoned over to cover the losses. I would guess that situation still prevails.

To the best of my recollection, eliminating the “sports tax” fees for students would have reduced their college costs by 40%. I doubt if college has gotten more affordable over the past 29 years.

The combination of semi-pro athletics and education is a uniquely American tradition. Elsewhere, the grooming of pre-professional athletes is handled by clubs, where there is no pretense of educational involvement. The only collegiate rivalry of note in England is the rowing competition between Cambridge and Oxford.

Educational institutions for education’s sake? It can be done.

Though composed of some of the oldest colleges in the country, the Ivy League was only formed in 1954. But those eight schools signed an Ivy Group Agreement in 1945 that stated, “Athletes shall be admitted as students and awarded financial aid only on the basis of the same academic standards and economic need as are applied to all other students.”

Specific athletic scholarships were banned, according to the American Football Database.

By 1945, the Ivies had been losing their status as elite sports teams, but, trailblazers that they were, they dominated early collegiate sports at a time when fewer schools were as well organized.

“In particular,” AFD documents: “Princeton won 26 recognized national championships in college football [last in 1935], and Yale won 18 [last in 1927].”

All in the past. Over and done. Well, college football was a big enough deal for Yale that its Yale Bowl, built in 1914, reached its final capacity of 64,269 in 1932. Only the departing Sooners and Longhorns have larger venues in the Big 12 today, with incoming Brigham Young also topping that figure.

Perhaps with a little biased pride, the Yale Daily News cites the Yale Bowl as the inspiration for the Rose Bowl, the LA Coliseum, Michigan Stadium and the Cotton Bowl.

And speaking of inspiration, OU’s “Boomer Sooner” carries the tune of Yale’s “Boola Boola.”

Yes, sports was once huge among the Ivies. But they decided that colleges should concentrate their resources on education. They do have ample resources.

OU fans complain about the money available at UT, which has $30.1 billion in its endowment plus many wealthy boosters. By comparison, OU’s endowment stands at $1.65 billion in second place just ahead of Kansas’ $1.61 billion. [Oklahoma State is fifth at $1.35 billion.]

As of October, Forbes reported the Ivy League endowments as: “Harvard [$53.2 billion], Yale [$42.3 billion], Princeton [$37.7 billion], UPENN [$20.5 billion], Columbia [$13.5 billion], Cornell [$10 billion], Dartmouth [$8.5 billion], and Brown [$6.9 billion].”

So, if those schools chose to invest in professional college sports, they could “kick butt and take names,” as we were wont to say.

The question, of course, is whether any other colleges will follow their lead toward a predominately educational mission now that their schools face invasion by outside forces whose money promises to undermine institutional control of their athletic programs and campus.

The time is ripe for such a radical reorientation of priorities …

But I guess the bigger question for the most people in the state is: Will Caleb stay or go?