BY RICHARD L. FRICKER

An Oklahoma County district judge’s ruling – once hailed as a victory for transparency by removing a legislative-imposed shroud of secrecy from the state’s execution protocol – was shred to tatters this week by the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

An Oklahoma County district judge’s ruling – once hailed as a victory for transparency by removing a legislative-imposed shroud of secrecy from the state’s execution protocol – was shred to tatters this week by the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

The high court ruling reset the clock, allowing Gov. Mary Fallin to become the second governor in state history to execute two inmates on the same day.

And, perhaps most importantly for the citizen at large, the ruling leaves open the question of whether or not the Supreme Court is, in fact, the final legal authority in the state. Or whether conservative Tea Party elements in the Legislature and administration achieved their long sought goal of breaching the separation of powers and gained political control of the state judiciary?

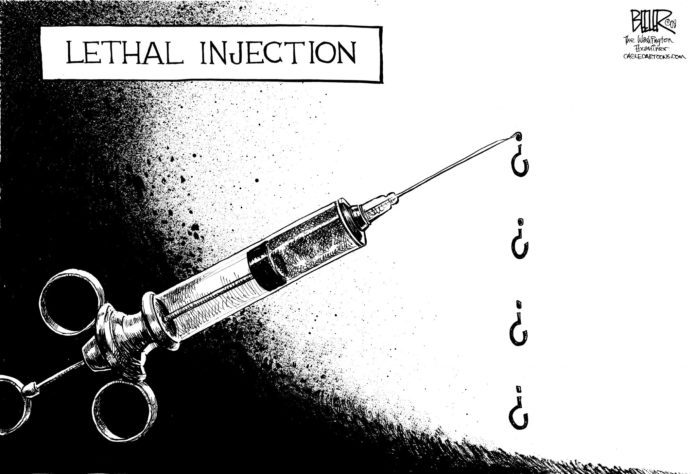

First the court’s ruling: Inmates Clayton Lockett and Charles Warner have been sentenced to die by lethal injection for separate but equally heinous murders. There has never been anything particularly sympathetic about their situation or questionable about their trials or their guilt.

Individually their cases have run the gamut of routine appeals. Each appeal has been denied.

The only question remaining was that of the manner and means of their deaths at state hands. Oklahoma law provides for a lethal injection of three drugs. Oklahoma was the first state to arrive at such a procedure.

Lockett and Warner challenged the state’s ability to provide the proper drugs for their executions, claiming that unless the state could provide information as to the origin of the drugs – and proof they had been tested and stored properly – they could not be assured of a quick and painless death.

Anything less, they contended would be cruel and unusual punishment – which is forbidden by law.

Their challenge was based on recent prohibitions by drug manufacturers to sell lethal drugs to states for execution purposes. States such as Oklahoma and Missouri had turned to compounding pharmacies for their dosages. These pharmacies are largely unregulated and have, at times, provided drugs of questionable quality.

Attorney General Scott Pruitt claims the state was under no obligation to provide such information and was in fact prevented from doing so by state law. Pruitt was referring to legislation passed in the 2010 session making all information regarding an execution – drugs, personnel, monies paid to executioners [$300 per body] and amounts paid for drugs – secret under all circumstances.

As the hearing progressed the Court of Criminal Appeals granted a temporary stay to their executions until April 22 for Lockett and April 29 for Warner.

On Mar. 26, Oklahoma County District Judge Patricia Parrish ruled the secrecy law unconstitutional. In so doing, she said, “I think the secrecy statute is a violation of due process because access to the courts has been denied.”

Her ruling on a statute enacted four years previous by a Legislature, possessed by having the ability to impose death on someone at a time when many states and countries were declaring executions inhumane, set the stage for a confrontation the results of which may not be fully realized for some time.

AG Pruitt appealed the ruling. The Court of Criminal appeals declined to make the stay permanent or to address the statutory issue.

Lockett and Warner appealed to the state Supreme Court. Under Oklahoma law the Court of Criminal Appeals adjudicates, as the name implies, only criminal matters. The Supreme Court acquires all other cases.

However, Judge Parrish’s ruling was on the legality of the statute, not on any matter or crime, trial or punishment. Thus the Supreme Court found itself in a place it did not want to be, but felt it should be in this particular matter.

On Apr. 21, the court issued an indefinite stay of execution while it reviewed the case. In short order, Gov. Fallin, a staunch supporter of the death penalty to the point she has already executed two men for whom the Pardon and Parole Board recommended clemency, saw her chance to do what the Legislature had been wanting to do since the Republican Party gained control, injecting herself – as head of the Executive Branch of government – into the Judicial Branch of government.

The separation of powers doctrine has been a part of the U.S. Constitution and the Oklahoma Constitution since their respective inceptions: Executive, Legislative and Judicial. However, over the past couple of sessions, the Legislative and Executive branches have been at odds with the Judicial branch because the court has struck down several laws near and dear to the Tea Party agenda, declaring them unconstitutional either on their face or because they did not comply to the construction required to become law.

Gov. Fallin challenged the court by issuing her own stay of execution for Lockett on Tuesday, setting execution for Apr. 29, the same day as Warner. In essence Fallin was telling the Supreme Court to give her a ruling, presumably one she and Pruitt liked, or she was going to proceed with the executions anyway.

For a governor to breach the separation of powers and challenge a high court was at the very least unheard of, most certainly in Oklahoma. The central reason for three branches of government was to provide for a judiciary free of political influence.

Fallin’s action immediately raised several questions: Could such a challenge succeed? Could she actually order someone killed in defiance of the high court? Who would or could stop her? As chief executive, her minions controlled the Department of Corrections and Department of Public Safety and her fellow traveler, the Attorney General, was from her party and at least as devoted to executions.

Was Fallin’s stay a serious legal challenge or an attempted coup on the court for having thrown out so much of her prized legislation? And, if successful, how much further will this intimidation extend?

If successful, would it be possible at some time in the near future – say in the case of Jones v. Mega Petroleum International – for this or another governor to force reversal of a court finding for Jones and allow Mega International to skip gleefully down the money road?

And lastly, if she executed Lockett and or Warner before the Supreme Court stay was lifted, would it be a crime? The legal experts contacted on this question replied almost verbatim, “I’m not ready to explore that question” or “I don’t feel comfortable answering that.” None, however, said no.

We will never know just how far Fallin, Pruitt and their minions were willing to go in their quest to enforce the death penalty.

Late Wednesday the Supreme Court reversed Judge Parrish’s ruling and lifted the stay of executions.

One source intimately familiar with the workings of the court said this was not the ground on which the court would choose to fight for its independence. But anyone watching the court, the Legislature and the governor knows a fight is coming.

Even as the court reviewed the Parrish ruling, Rep. Mike Christian, R-Oklahoma City, was introducing legislation calling for the impeachment of the five members of the court who voted for the stay of execution. Christian’s move wasn’t considered entirely foolish by many members who want judicial control.

Now that this issue has been settled by a unanimous vote it will be interesting to see if Christian’s move has any life left to live.

In the meantime Oklahomans are left to wonder: Did the court blink? Is the judiciary still independent – and if so, for how long? Do we still have courts of law or men? What can the common citizen expect from the courts – political correctness by agenda, or justice?

– Richard L. Fricker lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. His latest book, The Last Day of the War, is available at https://www.createspace.com/3804081 or at www.richardfricker.com.