Editor’s Note: Oklahoma’s first execution since it bungled Clayton Lockett’s last spring is set for Thursday evening when Charles Frederick Warner faces death by lethal injection. The Oklahoma Coalition to Abolish the Death penalty will hold a vigil outside the Governor’s Mansion in Oklahoma City starting at 5:15 p.m.

BY DANNY M. ADKISON

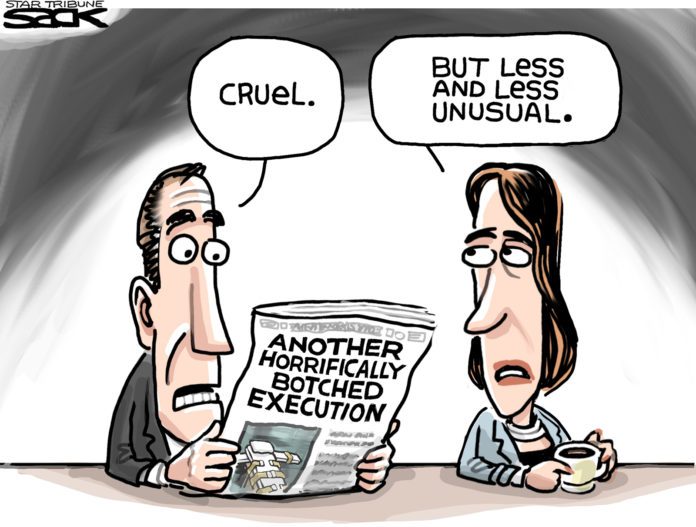

Oklahoma’s recent executions have raised questions about the state’s policies again. This is due to the so-called “botched” execution in April last year. That incident not only placed Oklahoma in the national spotlight, but raised serious questions about the lethal cocktail. It may be that Oklahoma has killed the death penalty.

Historically, Oklahoma has often been involved in important constitutional questions addressed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Here are just a few examples.

In 1915 the U.S. Supreme Court examined Oklahoma’s grandfather clause [which was mostly keeping African-Americans from voting], ruling it could no longer be used. In 1948 the Supreme Court showed it was serious about overturning the landmark Plessey case [allowing racial segregation] and ruled in the Sipuel case that the law school at the University of Oklahoma must admit an African-American as soon as it would enroll a white or close the university. The ruling became a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1976, in a case that originated in Stillwater, the Supreme Court first articulated the “heightened scrutiny test” which would be used to basically strike down laws treating men and women differently [Craig v. Boren].

Now, Oklahoma may find itself again before the Supreme Court again due to the “botched” execution of convicted murderer Clayton Lockett. Here are the facts surrounding that execution:

After prison officials declared Lockett unconscious – after, mind you, they had declared him unconscious – those witnessing the execution reported that he began to writhe and gasp. Some reporters described what they viewed as “agonizing” and as looking “like torture.”

A reporter for the Washington Post later reported that it appeared Lockett clinched his jaw, rolled his head from side to side, looked like he was trying to get up, exhaled loudly, and looked like he was in pain.

When Lockett uttered “man!” the reporters exchanged shocked glances, noticing that some journalists’ hands were shaking as they tried to take notes.

The prison officials finally closed the shades blocking the journalists’ view [even though they announced this would be temporary, they never opened the shades again]. What we now know is that about an hour after the prison officials started the execution, Lockett died of a heart attack. We also know that during the execution a lot of things went wrong.

While a lot of the facts are still unknown, it seems that the inability of the prison officials to properly insert the IV which was to administer the lethal cocktail was the primary cause of the botched execution.

Oklahoma says it has taken steps to prevent any more botched executions. Still, one would think that just based on what we currently know about the Lockett execution, this may be the worst case of botching an execution. It raises the question, has any execution gone as poorly as this, and if so what was learned from it?

The answer is the case of Willie Francis.

This was a case involving Louisiana executing Willie Francis, a young [he was 16 when convicted of murder] African-American in 1946. As with all executions, Willie was fed his last meal. He met with a minister [who walked with him to the execution chamber]. He was strapped into an electric chair and electrodes were attached to his body while a hood was placed over his head. The order was given to throw the switch.

Witnesses reported that Willie bucked so hard he raised the chair off the floor. His lips protruded such that it was visible with the hood on. Smoke came from his ears. Finally, Willie groaned and yelled, “Take it off, let me breathe!” Louisiana was using a portable electric chair [driven throughout the South on the back of a truck] and, apparently, it had malfunctioned. Willie did not die.

Incredibly, Louisiana scheduled Willie to be executed again a week later. A lawyer who took Willie’s case sought to prevent the execution on two constitution grounds: that electrocuting Willie would violate the constitutional doctrine known as “double jeopardy,” and that it would also violate the Constitution’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

Willie’s lawyer made an excellent argument before the Court that requiring Willie to again have a last meal and go through the whole stressful ordeal of starring down death a second time would clearly constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Willie was not executed a week later. It was about a year later that Louisiana executed him, incredibly, a second time.

How could this happen? The answer is too involved to give here, but it is important to note that the Court did, later, change its mind about Willie’s case [too late, though, to save Willie]. Had Willie’s case reappeared about 11 years later, he would not have been executed.

This is one of the major arguments with the death penalty. It is hard to correct errors.

Now, having botched the execution of Lockett last year Oklahoma may, by insisting on using the same “lethal cocktail” it used in his case, result in the Supreme Court revisiting the question of whether the death penalty, in general, and the lethal cocktail, in particular, constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

– Dr. Danny M. Adkison teaches constitutional law at Oklahoma State University and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer