BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

With the 2016 election cycle in full swing, the usual cast of characters has started to come out of the woodwork. I don’t mean the baffling roster of big-name candidates, also-rans, and “who?”s trying to cram into the presidential election clown car.

With the 2016 election cycle in full swing, the usual cast of characters has started to come out of the woodwork. I don’t mean the baffling roster of big-name candidates, also-rans, and “who?”s trying to cram into the presidential election clown car.

Instead, I mean to draw attention to the schedule of policies that has to make the rounds at least once every four years. Put whatever sharp-tongued demagogue, or manufactured corporate mouthpiece you want up there, they all sing from the same hymnal.

One of the most prominent of those all-too-familiar songs has already shown up in a couple of places: the flat tax. From Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom to Herman Cain’s Sim City-inspired “9-9-9” plan to the Rand Paul campaign’s rehashing of Jerry Brown’s 1992 plan, we’re all more than familiar with the basics. Doing your taxes is a pain because the tax code is too complicated and too biased, so let’s just have everyone pay at a single rate and move on.

As someone who’s done tax policy work, let me tell you, it’s far worse than you probably think. The tax code itself – the laws enacted by Congress – is roughly the size of a New York City phone book. The administrative rules – the regulations issued by the IRS to implement the laws – could easily fill a standard library bookshelf. And the body of interpreting case law, IRS opinion letters, etc. that fill in the details could probably fill an entire library.

This level of complexity makes the case for a flat or highly simplified tax almost a no-brainer. But it’s worth asking just how the tax system got so complicated in the first place.

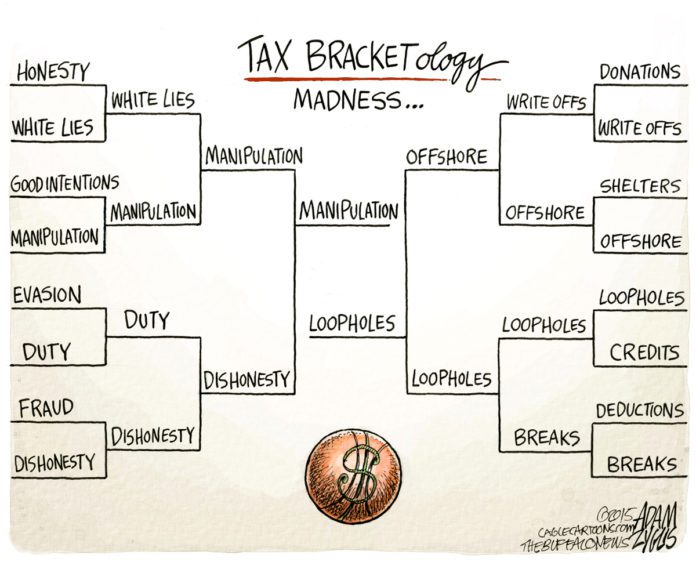

The easy answer is that special interests have loaded it up with special giveaways, handouts and loopholes. However, it’s not quite that easy. Remember that large corporations are special interests, but so are first-time home buyers, non-profit organizations, small businesses, single parents, etc. Special interests have always been with us, and are even central to the Constitution’s theoretical architecture. The problem is not so much that special interests exist, but rather that some have outsized power over the political process and that they all only have the public interest at heart by accident.

Another answer is that the tax code is complicated because the economy is complicated. All of these special deductions, exemptions, etc. represent efforts on the part of the government to encourage or discourage certain economic activities. The tax code itself is an extremely fascinating geological record of national economic debates, each layer of carve-outs representing a battle fought over just how important such and such industry or activity was to the nation.

We use the tax code as one of the primary tools to shape our economy. We want to encourage the formation of churches and philanthropic organizations, so we exempt them from paying income taxes. We want to encourage home ownership, and small business so we grant deductions. We want to discourage alcohol and tobacco use, so we attach taxes to them to make people think about how much they really want them. And any proposal to completely flatten out and simplify the tax code would lose all of those incentives and disincentives.

So before you can answer whether we should adopt a flat tax, you first have to answer whether you think the government should have a hand in shaping economic activity. If not, and you don’t mind a regressive tax structure, then a flat tax makes perfect sense. However, if you join the vast majority of the country in thinking that the government should have at least some hand in shaping the economy, then you have to ask how should it do it? Other than through the tax code, there are basically two ways.

The first way is direct regulation. We see this in our various illegal markets. We have outright forbidden the free markets in certain drugs, chattel slaves, etc. Direct regulation like this is probably the most straightforward way to discourage certain activities.

But using regulation to encourage other kinds of activities is a very tricky business. We can’t force people to do certain kinds of work, and there seems to be something very un-American and downright spooky about requiring education for certain careers or life-paths to ensure that the economy has what it needs.

The second way is through the use of subsidies. Rather than giving a break in taxes, we just cut a check to those doing the things that we want. We’ve used this tool to some effect in a variety of industries: agriculture, rural housing, conservation, food management, etc. But, if you want to replace all of the work the tax code does in the way of encouraging economic activities, then you end up with a complicated system of subsidies, qualifications, fraud monitoring, etc.

For example, we have a public policy in favor of encouraging the building of hospitals. Currently, the way we do this is to provide an income tax exemption for non-profit hospitals.

So let’s say we do away with that portion of the tax code, but still want to encourage hospitals to form. How are we going to do it? Should the government just take responsibility for all the hospitals? That’s certainly one solution, but not one most flat-taxers would support. Should we force people to form private hospitals? Not only is that crazy, but it’s also unconstitutional.

Maybe we should simply provide a direct subsidy – form a hospital, get a check? We could certainly do that, but then we have to ask who’s going to get a check? Should Baptist Medical Center get one? Sure. But what about an acupuncture center? OK, why not?

What about a hospital that uses traditional medicine: come in and get a bowl of chicken soup for $5.99, upgrade your treatment with crackers and a drink for $.99, clinic located in the Quail Springs Mall food court? It’s a silly example, but once you decide to grant a benefit, you have to decide who gets it and who doesn’t. Once you do that, you need law, a regulation, and a handful of court cases to figure out just where that line is. So instead of a system of tax law that fills a library, you end up with a system of subsidy law that does the same.

Adopting a flat tax will make filing your 1040s a lot easier, but it won’t make your life any easier. Unless you’re willing to accept an economic police state, or to put your faith in a completely free market, flattening the tax code only relocates the problem.

The tax code does need a thorough cleaning out, but simply erasing it is a simpleminded approach to a very complex and perhaps unavoidable problem.

– Christiaan Mitchell is a lawyer who holds master’s degrees in philosophy and education. He lives in Bartlesville and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer.