Baseball returns April 1. Opening Day. The high holy day on my calendar.

This is a political site? Unfortunately, baseball politics often out-stinks that of a governmental ilk. Talking about the Baseball Hall of Fame, of course, which sometimes seems to exist only to insult players and the intelligence of baseball fans.

This year’s induction ceremony will honor the Class of 2020 – deprived of a trip to Cooperstown last year – but no members from the 2021 ballot since the Baseball Writers’ Association of America deemed no one worthy this year.

They managed to honor Derek Jeter and Larry Walker last year. They will be enshrined along with Ted Simmons, from one of the veteran panels, and Marvin Miller, the former Players Association executive director, who led the successful fight for the economic liberation of ballplayers.

But this year’s vote stiffed Scott Rolen, a Top 10 third baseman of all time, who managed 52.9% of the votes [with 75 percent required]. This is an improvement from 35.3% of the voters last year. Rolen, of course, added nothing to his resume over that time.

Baseball Reference shows Rolen’s Wins Against Replacement [WAR] of 70.1 as 68th all time among position players and 10th among third basemen. This puts him ahead of such stalwart HoFers as Big Ed Delahanty, Tony Gwynn, Eddie Murray, Ryne Sandberg, Bucketfoot Al Simmons, Ernie Banks, Goose Goslin, Duke Snider, Willie McCovey, Home Run Baker and a legion of others.

Sabremetricians at The Hall of Stats, with a more complicated grading system, rate him the eighth best hot corner coverer ever, with his HoS rating of 140 – more than Hall of Fame third basemen George Kell and Pie Traynor combined [129]. The lowest ranking third baseman in the Hall is Freddie Lindstrom, whose story is another chapter in Hall perfidy. Lindstrom’s HoS rating of 48 [71st at the position] is barely a third of Rolen’s.

So, with today’s baseball writers allegedly educated by Bill James – whose statistical revolution changed how the game is now played, which makes him Hall-worthy as well – why isn’t Scott Rolen, one of the best third basemen ever, in the Hall of Fame? Right off the bat, no questions asked?

Well, slighting third basemen is a Hall tradition. With Adrian Beltre [fifth at HoS] not yet eligible, eight other of the top 20 Hall of Stats third basemen are not enshrined at Cooperstown, with only Ron Cey’s 99 rating falling short of the 100 required for Hall of Stats honors. If you’re one of the top 14 players at your position over 150 years, you deserve to be in the Hall of Fame – Graig Nettles, Buddy Bell, Ken Boyer, Sal Bando.

We could run similar scenarios for a couple dozen other players, the most egregiously slighted being Lou Whitaker.

Scott Rolen did not improve over his year of inactivity, yet his vote total increased. That speaks to a “make him wait” mentality that disgraces the call of the Hall to honor its best players.

PLAY NICE

A second, even less honorable, tradition is to punish players for non-performance issues, mainly their perceived disagreeability.

A much publicized snub this year was Curt Schilling, falling 16 votes short of glory in the ninth of 10 years of eligibility before he falls to a veterans panel. Among other things, Schilling has compared Muslims to Nazis; called for lynching journalists; supported the attempted Jan. 6 Capitol coup and attacked transgender rights.

But Curt Schilling could pitch. The Baseball Reference WAR rankings show him as the 26th best pitcher ever, right behind Bob Gibson and Ferguson Jenkins. The Hall of Stats folks rank him 16th, ahead of those two immortals – plus Eddie Plank, Steve Carlton, Tom Glavine and Nolan Ryan among 300-game winners as well as Robin Roberts, Carl Hubbell, Bob Feller, Jim Palmer and Mordecai Peter Centennial “Three-Fingers” Brown, Juan Marichal … and, well, you get the picture.

His politics are not mine, and I was surprised by his high rankings since his overall record is a “mere” 216-146. But he did lead three different teams to four World Series, won three of those and went 11-2 in the post-season. Fame? How about the bloody sock game?

Schilling would not be the first – nor likely the worst – jerk in the Hall of Fame. Cap Anson reverse integrated baseball and triggered 60 years of MLB segregation.

Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby have the two highest batting averages in MLB history – and joint reputations as among the most disagreeable folks to ever play the game. Cobb was also prone to violent outbursts. And then there are the stars with drinking excesses and unsociable social behavior.

One candidate for greatest hitter of all time, Ted Williams, maintained a strained relationship with his religious [Salvation Army], Mexican-American mother, “and he concealed the fact that he was Mexican-American all of his life, worried that prejudice of the day would hurt his baseball career,” Ben Bradlee Jr., explained in his biography: The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams.

Schilling was so disgusted with this year’s vote that he asked to be taken off the ballot in his last year of BBWA eligibility next year, which will certainly further endear him to the writers.

Just a notch below Schilling in standard stats [211-144], advanced stats and rotten disposition sits Kevin Brown, judged better than everyone on the second list above starting with King Carl Hubbell. In one of his Historical Baseball Abstracts, Bill James ranks him as the third best pitcher of the 1990’s, just behind Roger Clemens and Greg Maddux and ahead of Randy Johnson and Tom Glavine.

In ranking him as the 73rd best pitcher ever while Brown was still active, James’ only comment was: “I don’t root for him, either. But he is a great pitcher.”

In The Yankee Years, Tom Verducci, from Joe Torre’s perspective, notes “Brown had a famously rotten temper and a surly disposition.”

Yankees bullpen catcher Mike Borzello summed it up: “Kevin Brown. Some guys just hated him.”

In 2011, his first year of HoF eligibility, Brown garnered 2.1% of the vote, a bit low for a top 30 HoS pitcher of all time, and fell off the ballot. Don’t have to worry about that bad attitude any more. And yet, old-time HoFers Jesse Burkett and Johnny Evers were both so cordial that each was nicknamed “The Crab.”

Dick Allen, Gary Sheffield and Bobby Bonds were also regarded as having bad manners for speaking out against perceived mistreatment. Really solid HoF cases can be made for each of them. Bonds’ son Barry watched and learned from how his dad was treated and was on guard and defensive – and often just a plain jerk – throughout his career.

FRIENDS WITH BENEFITS – 1

While it doesn’t pay to make enemies among Hall of Fame selectors, having friends in high places can work wonders, which gets us back to Freddie Lindstrom – or, more accurately, to the Fordham Flash, Frankie Frisch.

One of the first great switch-hitters, Frisch was a Top 10 second baseman and among that position’s best fielders. He also served on the HoF Veterans Committee from 1967-1973. Bill Terry a former Giant and Hall teammate joined him in 1971.

This began an era of cronyism unprecedented at the Hall. In his seven years, Frisch teammates, Jesse Haines and Chick Hafey from the Cardinals and Dave Bancroft, Ross Youngs and George Kelly from the Giants were selected. [Bancroft played the bulk of his career elsewhere, but was on Giants pennant winners with Frisch from 1921-23.]

Frisch died in a car wreck on his way home from the ’73 vote, but we can figure that Terry was instrumental in getting Frisch’s St. Louis first base teammate Jim Bottomley elected the next year. Sunny Jim ended up with gaudier numbers due to the live-ball explosion, but the leveling experts shows his WAR at 35.0, compared to later Cardinals first baseman Bill White’s 38.7 from a shorter career.

Working from the same template, we can figure Terry was instrumental in enshrining his and Frisch’s former teammate Freddie Lindstrom, a fifth member of their infield, in 1976. HoS rates him as the 71st best third sacker ever, which is below that of perennial trivia answer Harry Steinfeldt at 68.

Bancroft, especially, and another Giants shortstop from the 1920’s and ‘30’s, Travis Jackson, who joined the immortals in 1982, were solid enough players that non-teammates might mount campaigns for them. High Pockets Kelly, though, is considered the 104th best [HoS] first baseman ever, right behind Charlie “Piano Legs” Hickman.

A SLIDING SCALE

Let’s say you have a favorite player with a pretty decent career, say someone with a WAR between 44.3 and 44.6. Chuck Knoblauch, Rocky Colavito, Matt Holliday, Troy Tulowitzki and Nomar Garciaparra were stars, the last two derailed by injuries. Looking down the WAR list of position players, you’ll find two dozen Hall of Famers [and hundreds of other players] before you get to George Kelly at 24.9.

But just as you’re making your case that your guy deserves induction based on that evidence, someone will pipe up, “But he’s no Willie Mays; he’s no Mickey Mantle.” The proper reply is, “Nobody else is either.”

Ted Simmons, one of this year’s inductees, was one of the most productive catchers in history, but he was criticized and penalized because of a certain contemporary. Simmons “was no Johnny Bench,” the greatest catcher ever. And while Simmons’ defense was offensive, he only cost his teams about two runs a year, according to Michael A. Humphreys in Wizardry. His bat made up for that.

Joe Torre, almost as effective a hitter as Simmons, was likewise slighted and made the Hall only as a manager, not for being one of the top dozen catchers ever.

Sportswriters spent the ‘60s making fun of Torre’s weight, perhaps not realizing in those statistical dark ages that, according to Humphreys, he was saving his teams more runs with his defense than Yogi Berra – in about half as many games behind the plate before he switched to the corner bases.

REWRITING HISTORY

These were the same guys [only guys then] telling us what a slacker Roberto Clemente was because he wouldn’t play hurt. When Clemente died heroically on a humanitarian mission to aid earthquake victims, a change in that narrative became necessary. At the time of his death while still playing All-Star caliber ball, he had the 18th highest career WAR [now 25th]. His talent and accomplishments also provided an impetus to ease on over to the right side of his story.

But this has led to a skewing of history as people lobbying to retire Clemente’s number [21], a la Jackie Robinson’s 42, claim he was the first great Latin player in the game. Except he wasn’t.

Though Clemente arrived on the scene three years earlier, his fellow Puerto Rican Orlando Cepeda burst onto the scene with monstrous standard batting numbers [the only ones we had with which to judge their worth]. These now translate into a slight edge on the sabremetrical level – until Cepeda wrecked his knee in 1964 and Clemente hit his mature stride.

But they both followed the first great modern era Latin ballplayer – Cuba’s Minnie Miñoso, a seven-time All-Star from 1951-1960, a three-time Gold Glover though the award wasn’t established until he was in his 30s. He won the inaugural honor in 1957 when only three outfielders were chosen.

The Hall of Stats shows him as the 22nd best left fielder in history, ahead of Ralph Kiner, Jim Rice, Heinie Manush, Hugh Duffy, Lou Brock and, of course, Chick Hafey.

His 50.2 career WAR actually bests Cepeda’s injury-plagued 50.1, as well as other HoFers such as Nellie Fox, Mickey Cochrane [injury], Kiki Cuyler, King Kelly and Chuck Klein.

And another point to be made about Miñoso’s deserved enshrinement is that he played three years in the Negro Leagues, the last two as an All-Star, before getting his chance in the Majors. His very worthy numbers should have been even better.

His exclusion from the Hall ranks with the dissing of Lou Whitaker as the Hall’s worst stains and as shameful as its cronyism. Honor Clemente, but acknowledge and honor Minnie as well.

I owned a 1958 Minnie Minoso baseball card. I’ve known how good he was for a long time. But it was only within the past year that I stumbled upon his Baseball Reference listing and discovered that tilde. The shock was sort of like seeing Alex Treviño’s name on the back of his uniform and realizing that my favorite golfer had likely had his name mispronounced his entire career. Where is Jay [can’t call him Jesus because we don’t know how to pronounce Spanish] Alou when you need him?

FRIENDS WITH BENEFITS – 2

Miñoso also easily tops Harold Baines, a 2018 inductee whose 38.7 WAR [same as Bill White’s] ranks 359th all time among non-pitchers.

But Baines had former owner Jerry Reinsdorf, former general manager Pat Gillick, former manager Tony La Russa and former teammate Roberto Alomar on the committee that chose him. I always liked Baines – good guy, good steady player. But I was a Bill White fan, too.

Along with those already mentioned, it would only raise the overall quality at Cooperstown with the addition of plaques for Luis Tiant, Todd Helton, Keith Hernandez, Bobby Grich, Bert Campaneris, Reggie Smith, Jim Edmonds, Bill Freehan, Bobby Mathews and Jim Wynn.

I feel certain that if Campaneris and Dave Concepción were both playing shortstop in New York for the dominant teams of their times, they would both already be enshrined a la Reese and Rizzuto. [Pee Wee was better than Bert who was better than Phil who was better than Dave.]

LOOKING FOR AN EDGE

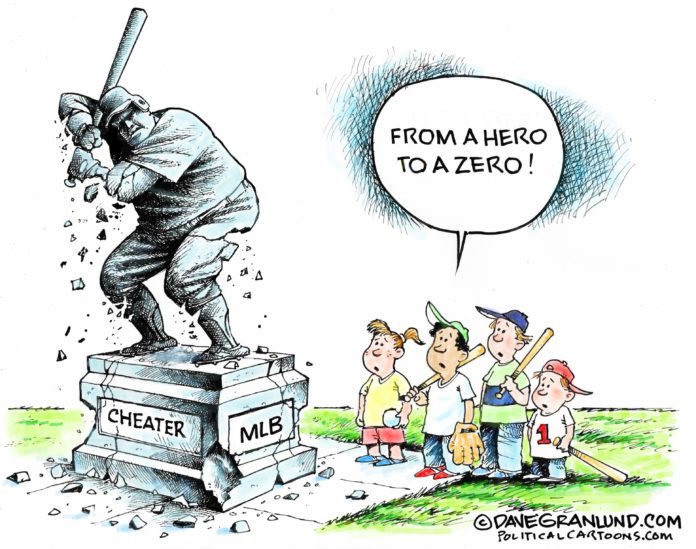

I’ve written this much about Baseball Hall of Fame politics without mentioning steroids?

Baseball fans love statistics. Still, most of us are smart enough to accept that Steroid Era numbers are skewed historically but true to their time. Some of the offenders were the best while they played and were recognized as such.

Between Schilling and Rolen on this year’s ballot were Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens at 61.8% and 61.6%, respectively. They are suspected steroid users – with no actual proof. Some folks are outraged that they are so close to glory.

Well, hold your nose and let them and the other steroid stars in. Their performances contributed to the outcome of the games, the pennants, the playoffs. Those records count; the guys who made that happen should count as well.

Furthermore, there is a ridiculous double standard applied to the players suspected of, or later caught, using performance enhancing drugs and others who benefited from their performances.

Coming out of the 1994 strike that cost us a World Series, baseball was looking for an attendance magnet. This was provided by the home run battles between Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire, whose extra kick concoction was visible in his clubhouse locker – because it was not illegal.

Leading the cheers for baseball was Commissioner Bud Selig, who looked the other way on PEDs long enough for the Steroid Era to cover more than 15 years while baseball attendance soared. Despite his neglect and tacit encouragement, the Today’s Game Era Committee voted Selig into the Hall.

Also there is Harold Baines’ old manager, Tony La Russa, whose Bash Brothers in Oakland [centered on José Canseco and McGwire] seem to be the most accepted starting point for the PED surge. And La Russa brought McGwire to St. Louis.

Certainly, if the players’ stats are tainted, the wins accumulated by their manager should be reviled and not revered. Ditto for the “leadership” that earned Selig his spot in Valhalla.

Hypocrisy aside, remember that baseball’s banned substances were not banned most of that time. And “If you’re not cheating, you’re not trying” is a mantra as old as the game.

Ground crews maintain the length of the infield grass and the hardness [or dampness] of the field to benefit the home team.

Bill James or one of his contributors found in the ‘80s that the Twins had statistically significant more home runs in the Metrodome than competitors. He joked about manipulating the air conditioning. And a Twins employee confirmed that years later.

Canseco arrived in Oakland in 1987, not that far removed from 1983, when Philadelphia’s pennant-winning Wheeze Kids reportedly kept amphetamines [“greenies”] in a jar in the trainer’s room as available as Ronald Reagan’s jelly beans.

That team included Pete Rose and four Hall of Famers, including the greatest third baseman ever, Mike Schmidt. In 2005, he told Murray Chass of The New York Times that amphetamines “have been around the league forever … In my day, they were widely available in major-league clubhouses … A couple times in my career I bit on it.”

Chass’s article adds: “At a drug trial in Pittsburgh in 1985, Dale Berra and Dave Parker testified that Willie Stargell and Bill Madlock dispensed greenies to their teammates. John Milner told the jury that Willie Mays had a bottle of red juice, or liquid amphetamines, in his locker when they played for the Mets.”

Stargell was a first-ballot HoFer. Bill Madlock won four batting titles. And Willie Mays is Willie Mays. [The Pittsburgh trial was concerned with cocaine usage in baseball, not the commonly accepted amphetamines.]

And the players caught using steroid once they were outlawed?

Well, Gaylord Perry pitched 22 years and won 314 ballgames doctoring baseballs – nudge, nudge, wink, wink – only getting ejected once, in 1982. His 1974 autobiography was titled Me and the Spitter. He was voted into the Hall of Fame his third year of eligibility by the guardians of the game’s integrity.

We should judge the players on their performances, not their personalities, and their performances under the playing conditions accepted at that time.

And – if you’re wondering – baseball people gambling on baseball games have been banished for life since the 1870s.

Oh, yeah. Harry Steinfeldt was the third baseman on the Tinker to Evers to Chance infield of the Chicago Cubs, part of the winningest collection of ballplayers ever assembled.