BY JOHN WOOD

Atop the Oklahoma Capitol dome stands the Guardian, a 17-foot, 6,000-pound bronze statue of an American Indian warrior with shield and lance in hand. The working oil rig fenced in a nearby parking lot is not likely lost on his gaze. While some, tongue in cheek, say, “He’s got his weary eyes on Texas,” others say the Guardian reflects Oklahoma’s heritage, according to its creator, former state Sen. Enoch Kelly Haney.

The state Capitol is dubbed, not unlike all other state legislature buildings, as the “people’s house.” It might by all appearances seem “open” to the public, but in reality, only so much.

For more than a decade, I’ve brought my students to tour the Oklahoma State Capitol. It’s worth it despite its noisy, confusing maze of a building with constituents, legislators, and lobbyists roving, albeit in the palatial granite halls accented with Indiana limestone. My students, in “ahhhh” with their surroundings, would visit their Legislature – sometimes eagerly, other times bewilderingly viewing floor action from the gallery. We would then take a frameable grand staircase picture of students posing with area legislators.

Walking these beautiful halls belie the fact that while we can explore the Capitol’s historic hallways and watch legislators’ debate from the gallery, we can’t take photos of the floor. It’s important that we can speak to our legislators one-on-one or in a group, but that is only if they can find time for us competing with corporate lobbyists hanging perpetually outside both chamber’s floors. We are not even privy to their caucus and committee meetings where the real deal-making happens. What deals where made?

We are likewise limited in our ability to learn about legislator financial information – an essential tool when trying to get to the bottom of potential conflicts of interest that could arise. Why the secrecy?

The fact is that after two years, on a larger scale, it should not be lost on us that we still do not have IRS tax records for our president. It makes me think, “What are you trying to hide?”

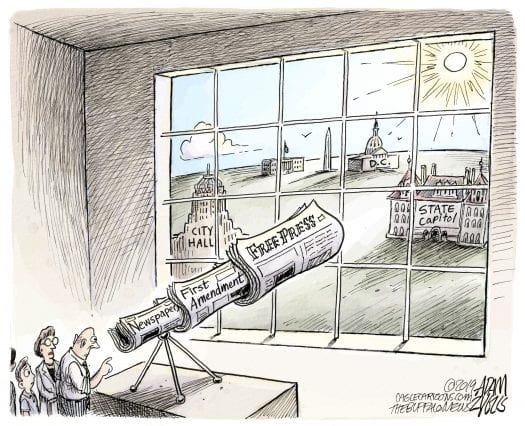

Shining light on our government is one way to do this – through ensuring and facilitating the public’s right of access to and review of public records. Lest we forget they are the People’s records. In this way, they may be empowered to efficiently and intelligently exercise their inherent rights.

Chances are that anytime you watch or read an expose in the news, it is likely made possible – in part, if not wholly – by reporters armed with the Freedom of Information Act [FOIA].

Example: the Bush Administration’s Iraq torture policy was revealed through an American Civil Liberties Union FOIA request. Closer to home was former Gov. Mary Fallin’s foot-dragging when it came to disclosing emails and other documents that revealed her handling – or mishandling – of capital punishment.

The Flint water crisis and the uproar over delayed veterans benefits also were first reported because of FOIA.

What’s common among these stories is that the People’s access to information is obstructed to the point where in limiting access, we no longer can make sense of the dizzying world around us. If the Capitol is truly the People’s House, then we need information about legislative decision making.

BRINGING THE SUNSHINE

As an educator, I often think about Jefferson’s quote: “Whenever the people are well-informed, they can be trusted with their own government.” Trust and knowledge in balance. In other words, free government relies on enlightened citizen self-governance, best achieved over generations through education and government transparency. Jefferson’s ideas resonate today.

Joe Wertz, who is the senior investigative reporter at the Center for Public Integrity and past president of Freedom of Information Oklahoma, told me: “Open records and meetings laws are essential to preserving and promoting the public’s right to know what their government is doing and evaluate how well our representatives are serving that trust.”

Lack of trust can lead to calls for greater transparency.

Public Administration Professor Alasdair Roberts claims the Public Right to Know movement originated in response to New Deal reforms and people’s fear of “Big Government.” On top of it, George Orwell’s fiction novel 1984 stoked people’s imagination.

So, it was not surprising to find then that the American Society of News Editors published The People’s Right to Know soon after. It was a significant, but underrated historical moment. After all, it was the first “scholarly, legally documented presentation on the subject,” calling for freedom of information in the United States. Three years later, the Columbia University Press gave these sunshine laws more legitimacy and wider dissemination.

In response to this Right to Know movement’s spotlight, President Johnson in 1966 enacted the Freedom of Information Act, despite misgivings. The Watergate scandal further triggered amendments eight years later – though Congress had to override President Ford’s veto to enact them. Soon after Ralph Nader criticized the lack of federal implementation of the law.

Two years later, a legislatively-referred constitutional state question – the Oklahoma Legislative Conflict of Interest Amendment – was approved by voters. It prohibited legislators from “engaging in activities or having interests which conflicted with their duties and responsibilities.” It’s hard to ensure legislator accountability without empowering citizens through transparency laws, given a prevailing environment of secrecy, where conflicts of interest are easily hidden.

Nine years later, the Oklahoma Open Meeting Act, also known as “Oklahoma’s Sunshine Laws,” was signed into law by former Gov. David Boren, but excluded legislators and a few other state agencies – including the judiciary – because they were not considered a “public body,” according to Oklahoma Statute Title 51, Section 24a.3(2).

Because of this exception, Oklahoma remains one of only eight states in which legislators explicitly exempt themselves from the people’s right to know.

Unfortunately, the attitude at the state Capitol has largely been one of indifference. Legislators possess the power to end the exemption, yet are clearly reluctant to act. For example, Oklahoma’s Legislature consistently beat back efforts to open up current closed meetings legislation – whether proposed by Democrats like Chickasha Rep. David Perryman or Republicans like former Rep. Jason Murphey. I guess you might not be surprised then that in the 2015’s Center for Public Integrity report, it states Oklahoma deserved an “F” in transparency and accountability?

It also seems unfair that local officials have to abide by Sunshine Laws – why would legislators be an exception? Former Norman Mayor Cindy Simon Rosenthal told me, “I certainly think the public would benefit from more openness at the Capitol.”

In my time on Guthrie’s City Council, I remember the city manager telling me I had to locate and provide all my emails involving another council member in order to fulfill an FOIA request. Such requests are not fun or easy, but important for transparency and accountability on council. We also had to abide by open meetings act requirements for all meetings.

I’m amazed that as a council member I could represent 10,000-plus lives and influence a multi-million-dollar budget – all subject to sunshine laws – while state lawmakers who can affect billions of dollars and four million-plus lives can operate in relative secrecy, behind closed doors. Seems hypocritical to me.

This is unfortune too because, “[c]itizens have a right to know what their government is doing to make well-informed decisions about matters affecting them and their communities,” says Dick Pryor, KGOU general manager and FOI Oklahoma board member, “An independent press is expected to serve as a watchdog to hold elected officials and powerful institutions accountable to the people.”

Pryor channels the former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who explained that sunshine laws are like “shin[ing] the light” of information on what was once hidden from public view.

CLEAN MISSOURI

As mentioned in my last column [April 2019 Observer], Clean Missouri passed by a large majority in November 2018 – 62% “yes” votes of more than two million votes. That’s huge! Clean Missouri deals with five reforms, one of which, opens up their Legislature to the sunshine.

Clean Missouri’s language states that the Legislature shall be open to “public records and subject to generally applicable state laws governing public access to public records.” This includes opening up committee meetings in both chambers and opens to public view paper and electronic records of “the official acts of the general assembly, of the official acts of legislative committees, of the official acts of members of the general assembly, of individual legislators, their employees and staff, of the conduct of legislative business and all records,” according to the ballot language. If we could just achieve this level of transparency, we would be a long way to Jefferson’s ideal balance between trust and knowledge.

Haney’s Guardian is not just a reminder of our state heritage. It also serves notice our legislators – who are supposed to guard us – are often working instead for themselves, behind closed doors. The true Guardians are the people. The Legislature will gain trust through openness. The doors should be open to us.

It took a battering ram by Missouri citizens to force the legislature’s doors open and it’ll also take a similar effort here as well.

Judy Gibbs Robinson, retired journalism instructor and member of the FOIO Board of Directors, I think sums it up pretty well to me, “Without open records, citizens have no way of knowing what their government is doing except for what that government tells them. Now more than ever we need citizens to request and check records to hold government officials accountable. It’s irresponsible to accept without question what we’re told. This ‘self-governance’ stuff isn’t for sissies!”

– John Wood is an associate professor of political science at the University of Central Oklahoma. The views he expresses are his and not necessarily the university’s.

Editor’s Note: This essay first appeared in the May 2019 print edition of The Oklahoma Observer. The third installment in this series is scheduled to appear in the July 2019 Observer.