First In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

Every four years, the United States re-enacts one of our greatest cultural achievements: we have a contest for supreme political leadership that has only ended in bloodshed once in 226 years. Unfortunately, it also seems to amplify everything that’s wrong with modern America.

So far this cycle has already shown the crassness, racism, and wealth-idolatry that characterizes far too much of our electorate; and the narrow-mindedness, secrecy, and dependence on wealthy donors that characterizes far too many of our politicians.

It has also presented us with a problem that gets more important with each go-around: “What are we going to do with these Millennials?” In particular, as Millennials are aging into political majority – the oldest now reaching their mid-30s – our disengagement is becoming a vital issue for our democracy. How can we hope to survive as a democratic republic if the nation’s largest age cohortis abandoning politics at historic rates? And, more to the point, what can we do to reverse this trend?

There have been volumes written about Millennials. And many people, usually and notably non-Millennials, are justifiably sick and tired of hearing about us. But so much of what’s written misses the fundamental [and to my mind obvious] political problem, that it’s worthwhile to at least try to talk plainly about where it comes from.

Some Facts About Millennial Disengagement

Recent electoral data shows historic lows in voter turnout both locallyand nationally. According to the US Census Bureau, voter turnout in the last election was 41.9%, the lowest rate in nearly 40 years. It was a mid-term election, which typically have lower turnouts, but even by those standards it was an abysmal year. Turnout among Millennials was particularly wanting: only 21.3% voted nationally.

Recent research has found that traditional political involvement among Millennialsis even more dismal. As a generation Millennials are more prone to volunteerism, but are still highlyreluctant to participate in our political parties.

These trends not only hurt Millennials’ long-term interests, but raise fundamental questions about whether American democracy itself can survive. An old professor of mine used to ask, “Can democracy survive if it depends on people like us?” Given this level of disengagement, I have to join him in fearing that the answer is “no.”

What’s Going on Here?

While that’s certainly a depressing thought, the proposed responses to the problem are even worse. As politicians, analysts and pundits wrestle with this problem, they keep coming back to the same tired answers. We get solutions that are about making it easier to vote, simpler to register, easier to connect with [by which they mean “donate to”] this or that campaign.

Invariably, the Internet is somehow the solution to it all. Every one of the above solutions always involves online registration and voting, one-click donations, and so on. It’s as if they could just find the right app, then Millennials will miraculously start turning out in droves.

But all of this misses the true root of the problem. We Millennials already know how to use the Internet to find what we’re interested in. The problem is that the modern American political world doesn’t give us anything to be interested in!

As a generation, Millennials are seeking connection, and work that gives purposeand substance to our lives. We’ve certainly not turned away from making money, and we’re not any less interested than previous generations in having a comfortable life. But at the same time, and much to the consternation and baffling shock of our older relatives and would-be employers, we also insist that that not be the only things that matter to us.

The source of Millennial disengagement doesn’t come from our inability or unwillingness to get involved. It comes from the fact that American politics has been almost completely stripped of substance and meaning. As a result, it’s hard for us to see how participating in this impoverished system will add anything to our lives.

Baby Boomers, the Culture War, and Ideology

The poverty of our politics comes from the way the Culture War narrative interacts with our ideology-obsessed national politics.

We all spend a lot of time lamenting partisan gridlock in Congress. On one level, there’s nothing new in gridlock. In fact, some argue that the notion of gridlock is built into the very structure of our constitutional architecture. But the past decade has been a particularly bad stretch for us. It has seen unprecedented use of the filibuster,historically low levels of congressional activity, and the destructivenear-shutdown of government itself more than once.

Of course, we all know that this has been a function of an increasingly polarized Congressand electorate. But this rise in dysfunction is also correlated with Baby Boomer political supremacy. So we have to ask if there is some reason that, as the Baby Boomer generation has come increasingly into power, our governing systems have become dysfunctional?

Part of the answer to that question lies in the persistence of the Culture War. The term has largely fallen out of use, but its dynamics are very much still at play. For the uninitiated, the Culture War is a term for the struggle between progressivism and traditionalism in American values. Its roots stretch back to the 1920s, but it flared into a full-blown “hot war” during the 1960s. The term itself comes from the 1990s, when the conflict emerged as the defining locus of our politics. It waned in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 but returned shortly thereafter. And though it’s now unnamed, the underlying struggle remains as the “Yes We Cans” tussle with the “I want my country backs.”

On its own, the Culture War is little more than an overly dramatic description of a national debate over which of our social arrangements are working and which ones need to be altered. As the physical conditions of national life change, there is inevitably friction between those who operated best under the old conditions and those who long for something new. But in the hands of ideology-driven Baby Boomer political leadership, this otherwise completely normal process becomes scorched-earth, internecine warfare.

Culture War as Ideological Conflict

The real trouble comes from the fact that the Baby Boomers are what generational theorists call an “idealist generation.” In a short article for Brookings, Morley Winograd and Michael Hais describe the problem succinctly. “Idealist generations uncompromisingly adhere to … deeply held principles all of their lives. This pattern produces a challenge for the American political system, which is constitutionally based on institutions that require compromise and coalition-building to get things done.”

The fact that we have differing moral and political visions for the future of America is not the source of the problem. Rather it’s that those differing visions are held by people who are committed to a way of looking at the world that makes compromise impossible. For a position founded on principles, to compromise is to be compromised. And any inch of ground that is given up is a betrayal.

Worse yet, ideology-drive approach leads to a near-total immunity to evidence. If our worldview is based in principles, then our job is to live by those principles and any bad consequences are simply tests of our faith – if our solutions don’t fix the problem, the world is at fault rather than our solutions. As a result our politics is built on ideas of the way the world should be, rather than on the way the world is.

Millennial Disengagement

The net result is that the Culture War fails to be a vigorous dialogue between progressive and conservative visions of America. Instead it becomes farcical shouting match.

On the one side are regressives committed to returning America to a time of humble, pure innocence that exists only in fantastical childhood “memories” of the way America was. On the other is a conglomeration of special interest groups abstracting their commonalities into an American Jacobinism that would police everyone into an imagined utopia free from offense, struggle, and to a large extent personal responsibility.

Millennials are disengaged because it is impossible to take this circus sideshow slap-fight between caricatures seriously. If it were just entertainment, it would be fine. But it’s not. It’s what passes for politics in America, and it is having a disastrous effect on our future.

Our disengagement doesn’t spring from apathy. It springs from the fact that our future is being betrayed daily by the political system and those currently in charge of it.

Next week, the second article in this series will focus on some of the specifics of what that betrayal means for our political identity as a generation.

Second In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

Last week’s articlemade the case that Millennial political disengagement is a function of our disgust with an increasingly empty national political dialogue. It argued that our politics have been impoverished by a national dialogue dominated by ideology, at the expense of specific, evidence-based policy responses to concrete social problems. This has the effect of undermining Millennial political engagement and is having a devastating effect on our future.

But this raises two questions: First, is this problem a particular issue for Millennials in a way that justifies special attention? And secondly, if this is a unique problem deserving of special attention, then what is to be done? In this article, I try to answer the first question.

Who is the Millennial Generation?

Before we get too far down the road, it’s worth taking a minute to get clear on just whom I’m talking about. “Millennial” is one of the most contested terms in modern social discourse, one that a majority of Millennials actually reject.

Demographically speaking, Millennials are roughly the people born between 1980 and 2000. We are the first generation whose lives were essentially shaped by the Internet. We’re also the first generation whose political sensibilities were formed in the post-9/11 world. We are the children of the Reagan and Clinton eras who first started waking up during the [W.] Bush Administration. We are also the generation of the Obama Democrats.

But all of that doesn’t tell us much about who Millennials are. And it certainly doesn’t provide any kind of a foundation that would allow us to fashion a generational response to the slow-motion train wreck that passes for our government.

Yet there is a cluster of problems that we face that more or less uniquely apply to us. These facts paint a picture of a massive, inter-generational bait-and-switch and can form the core of a coherent political identity for Millennials. And in fact, “the Bait-and-Switch Generation” is a far more appropriate name for us than “Millennials.”

Who is the Bait-and-Switch Generation?

Put most simply, the Bait-and-Switch Generation is that group of us who are inheriting a country radically different from the one we were promised growing up. Perhaps more to the point, we are that generation of Americans who have spent the early part of our lives working, studying, and incurring massive financial obligations under the promise of a better future that is not likely to pan out.

While this roughly corresponds to Millennials, we’re only part of it. I don’t mean to point to a collection of demographic facts so much as a set of political facts. There are some demographic Millennials who wouldn’t count themselves as part of the Bait-and-Switch Generation, and there are Bait-and-Switchers who are not Millennials. But what we all share is that our futures have been profoundly betrayed by our political system.

How is this anything new?

Many people are going to be skeptical that there is anything unique in this experience. And some will claim that this is nothing more than just the whining of a privileged and entitled member of a generation that has never had to deal with the harsh realities of life. But there are three specific failures of our economic system that are enough to distinguish the Bait-and-Switch Generation:

[1] Caustic Student Loan Debt

Our outrageous student loan debts set us apart from previous generations and illustrate best the nature of the generational bait-and-switch. In July 2013, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reported that the collective student loan burden in this country had hit $1.2 trillion. Well over halfof that debt is held by people under 40, and roughly 42% of Millennialshave at least one person in their household with student loan debt. This represents is a looming economic disaster that threatens to hamper economic growth and prosperity for decades if it is not addressed.

[2] A Broken Economy

The student loan crisis wouldn’t be half as big a problem were we not entering into a fundamentally broken economic system. We are stepping into one of the worst job markets in the past 50 years– as recently as last year, the unemployment rate among 25 to 32 year-olds was the highest it has been since the Baby Boomers. For those of us lucky enough to have found work, wages have stagnated. This not only makes it difficult to pay our day-to-day expenses, including our massive student loan bills, but can cripple long-term finances. In particular it makes building personal net worth by saving while youngextremely difficult.

The economy also presents enormous problems for those among us who didn’t go to college or who hold smaller student loan burdens. Failing to get a college degree costs on average about $17,500 per year in lost earnings, and those who begin but don’t finish college have a much higher chance of defaultingon their smaller student loan balances.

[3] The Failure of Social Safety Nets

Our inability to save and build capital for our long-term financial stability is particularly troubling because we are also the first generation in 50 years for whom the social safety net will likely not be there.

In 2014 the Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trusteesreported that the Social Security Trust Fund will be depleted in 2033 – about 12 years before the oldest Millennials will be eligible for retirement. The fund will be able to continue paying about three-fourths benefits on tax revenues through 2088, about 11 years after our children are eligible for retirement. A similar fate awaits Medicare. The same report predicts that the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will be exhausted by 2030.

While there has been perennial handwringing over this mess, nothing has been done to actually fix it. But, unlike the generations who have created this mess, we are the ones who are actually going to have to pay the check.

Put most simply, we are coming into the world the most in-hock of any generation in recent history, having the slimmest chance in decadesof being able to climb our way out, and will have to face that reality with the help that other generations have been able to depend on. While there are signs that the economy is recovering, most of those gains are not being enjoyed by Millennials.

The Death of the American Dream

All of this adds up to the fact that absolutely distinguishes us from the generations that have come before: for us, the “American Dream” is dead.

We are likely to be the first generation in recent history that will inherent this country significantly worse off that it was for previous generations. We are delaying starting families, are less likely to own a home, and are increasingly less likely to stay in one job for long. We are facing later retirementand a less secure future, things unprecedented within living American memory.

Fortunately, we seem largely okwith losing much of that. But too much of it is driven by necessity. We are being forced to make these decisions and sacrifices because of the indulgence of those who came before us.

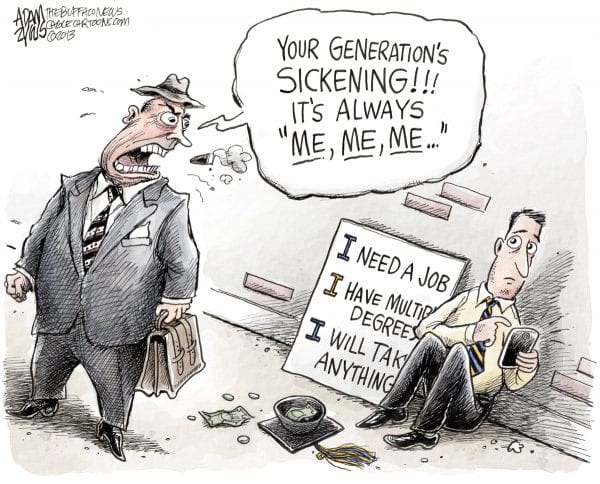

Perhaps most galling, we are basically told that it is our own fault: No one made us take on all this debt or to get all this education. And we are frankly unrealistic in our expectations of the kinds of work we will be doing once we make it into the workplace. The real problem, or so we’re told, is that we’re the victims of the “everybody gets a trophy” culture.

But you can only repeat a prediction with absolute confidence so many times before it becomes a promise. We were told our entire lives that this was the way forward: get an education and you’ll get a job, you’ll be the one sitting behind a desk giving orders instead of standing in front of it taking them, and so on.

In short, we were promised an America that would reward hard work and noble effort. It was an America that we fell in love with when we were young, and it was an America we committed ourselves to serving. And now that we’ve arrived, it’s simply not here.

Solutions

This situation did not simply happen. It is the direct result of specific, and concrete political decisions. Unfortunately for the Bait-and-Switch Generation, our interests have been ignored by the politics that have brought us to where we are today. This lack of attention is particularly damaging to our generation’s long-term prospects and is toxic to the continued existence of the middle class.

To whatever extent things are turning around, we have inadequate cause to have faith that the system will serve our interests any better than it has up to now. And why should we expect things to be different so long as the same people are in charge of the same system with the same structural issues that have gotten us to where we are today?

If we, as a generation, are going to get out of this mess, we’re going to have to act. But we have to be careful that we don’t fall into the same political patterns as our predecessors. We need a new politics for the Bait-and-Switch Generation.

Next week, the third article in this series will lay out some fundamental principles for what that politics will have to look like if we’re going to get ourselves back on track.

Third In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

Last week’s articlepresented two questions that Millennials have to ask if we want to move forward with addressing our disengagement from politics. Specifically, it asked if our disgust with the political process results from problems unique to Millennials, and if so, what are we to do?

In answer to the first question, I laid out an argument that the failures of our political system are leaving us a nation radically different from that which we were promised. This generational bait-and-switch, and the problems that are likely to flow from it, justifies a Millennial-focused approach to fixing our political system.

This rest of this series will be devoted to answering the second question: What do we do?

Making Our Political Ideas Clear

In the first article, I made the case that the root of Millennials’ political disengagement lays in the emptiness of our political dialogue. This emptiness results from the fact that our politics is discussed as abstract ideology, rather than as concrete policy-making. We can talk about our rights until we’re blue in the face, but they are fundamentally meaningless unless you can translate them into specific actions, policies, regulations, etc. Until you get something that can specifically limit or compel a particular person or persons, you’re only building castles in the sky.

If we’re going to rehabilitate our politics, then we’re going to have to start thinking about politics more Pragmatically. That means that we have to recognize that our politics will continue to be empty unless we obsessively focus our attention on the practical and verifiable consequences that flow from a given idea or policy proposal.

The debate over the Second Amendment provides a good example of what I mean. The conversation, particularly here in Oklahoma, is often viewed as an unbridgeable gap between people who believe that we have a right to guns and those who don’t. However, when it is framed instead in concrete, specific terms, it turns out that we all basically agree about the Second Amendment. Few people would say that a recently released violent felon with a history of mental illness ought to be able to walk into a Walmart and buy an AK-47 with a thousand rounds of ammunition.

In the concrete, we all agree that there is such a thing as reasonable gun regulations. Our task isn’t to reconcile incompatible principles. It’s to find a workable line between who should be allowed to buy guns and who shouldn’t. That discussion has to take place in the context of concrete particulars. However, our focus on the abstract Right to Bear Arms cripples that discussion and prevents any meaningful action to address a terrifyingly chronic problem.

But that’s just a single example. If we are going to build a new politics for this generation, we need to see what this move away from the abstract means more broadly.

Freedom

First, this approach puts to rest questions about the proper role of government. We have a long-standing national obsession with the proper role of government. We typically begin with some statement of first principles about why government was created. This then proceeds into a series of statements about what kinds of a government so created should be engaged in. And finally it ends in accepting or [usually] rejecting this or that course of action because it’s something government should or shouldn’t be doing.

However, a Pragmatic approach would focus our attention less on why government exists and more on what we get out of having a government. Instead of wedding ourselves to one [typically incomplete and/or inaccurate] version of history about why humans create states, we can start from the idea that it’s just something that we do that gives us certain positive results. It doesn’t matter why we organize states, what matters is what benefits we get from doing so and what further benefits we can realize by adopting this or that program.

This way, ideas like “government,” “the State,” and “Law” look less like metaphysical entities that dictate social forms, and more like tools that we use to organize ourselves to achieve common goals like stability, prosperity, security, etc. The extent to which we’re actually achieving those goals, rather than matching some idea about how things should be, becomes the way that we know whether what we’re doing is working.

In short, government becomes a tool for social progress rather than a god to be served.

Progress

Many will raise the concern that if we detach ourselves from a firm set of principles about the natural limitations of government, then we open the floodgates to all manner of tyrannies and un-Americanisms. Again, the Second Amendment debate is illustrative. We’re told that if we pull away from what the Supreme Court has decided was the Framer’s intent, then we get the Holocaust, Stalin, and Mao. But this reveals a profound mistrust of the American people and a complete lack of faith in the resilience of our cultural institutions to that kind of abject tyranny.

A Pragmatic reading of our system understands social progress as an evolutionary process. This not only involves experimentation with new forms and structures, but also the conservation of things that are working well. And our system is built on the fundamental faith that this conservatively progressive process can be well controlled and moderated by people’s engagement with social affairs. Provided, that is, that that engagement is tempered with a robust sense of what it means to have a healthy social dialogue.

For us, that means that we have to reject out of hand arguments that would tell us that this or that approach is not an appropriate thing for government to do. And we should view with equal suspicion those who insist that this or that change is going to destroy the character of America, and those who fall into the trap of wanting to change something simply because it’s traditional.

Instead, in every case we have to ask what benefits are we trying to garner, will this or that program give us those benefits, and finally what existing benefits will we lose if we adopt it? In short, we have to approach policy questions like adults. The extent to which this is a point that needs to be made is a good indicator of the depth of our current troubles.

Civility

If there is a single way in which our tendency towards abstract, ideology-driven politics has eroded our ability to function, it is that it has completely destroyed our sense of civility. By “civility” I mean more than simple politeness. Instead, I mean something closer to civitas, the sense that by participating in society we create something more than ourselves; that the social compact has a compelling existence of its own.

During the days of the Founders this idea found its expression in the notion of republican virtue. Put Pragmatically, it means taking what John Deweycalled the idea of democracy as a personal moral commitment.

The distinction between the idea and technology of democracy is crucial. Democracy’s technologies are things like representation, universal suffrage, party primaries, etc. However, the idea of democracy is something much deeper. It is the organizing principle that tells us that individuals have a right to benefit from and shape the common values of the groups they belong to [including our largest group: the nation], and that those groups have a right to demand the devotion and effort of their members to sustain those values.

For a Millennial politics, this means that we must renew our faith in two longstanding principles of American government. First, we have a right to insist that our voices be heard in the governing process, and as a part of that we have an obligation to ensure that all voices are heard. Secondly, we are obligated to participate in our public life beyond showing up once every four years to vote.

In short, we have to commit ourselves to taking the promotion of the public interest through public service as a personal moral obligation. For all of its flaws, our system is founded in the idea that we are the government.

Therefore, to the extent that we don’t engage in the process [at every level], we are complicit in everything that is going on.

The New Ideology

If our generation is going to have any hope for a livable future, we are going to have to create a way of thinking about public affairs that can rehabilitate our politics. In order for that to work, we will have to find something that avoids the ways of thinking that have caused us so much trouble. In short, we need an anti-ideology ideology.

By approaching the problem of government Pragmatically, we get at least three broad principles that can form a basis for this new approach. First, we should understand government as a tool for improving social conditions, rather than as some metaphysical being born to serve a set of abstract principles. Second, we should understand progress as an evolutionary process that, when approached with concrete and specific problems in mind, acts to conserve what works and improve what doesn’t. Finally, democratic government only works when every person takes engagement in public affairs for the common good as a personal goal.

Taken together, these ideas outline a picture of a generational politics that can reshape the way that our governmental institutions work.

The irony of laying out a set of political principles to call for fewer principles in politics should not be lost on anyone. Next week’s article will begin the process of filling in this sketch of what we need to do in the coming decades to get ourselves back on track.

Fourth In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

So far this series has focused on building a foundation for a Millennial-focused response to our political crisis. The first articleexplained that Millennials are disengaged from politics because we’re disgusted with its emptiness and lack of effectiveness. The second articlemade the case that Millennials can find a political identity in the slow-moving disaster created by this political dysfunction. Finally, last week’s installmentsketched out a basic foundation that responds to the root of our problem: ideology driven politics.

Throughout, this series has had a singular theme. We need to think about our politics concretely, and avoid the kind of ideological approaches that have sucked the substance out of our public life. This article presents some concrete suggestions for how we need to move forward.

Why so much theory?

First, I want to take a step back to explain why this series has spent so much time on political theory. If the goal is to get us thinking about politics as a concrete and specific thing, then it’s worth asking why half of this series has been devoted to developing a theory of Millennial politics?

I think it’s worth pointing out that Millennials have some sense of how to be politically active. After all, we put together one of the most significant political demonstrations in the past 30 years, Occupy Wall Street.

But Occupy also illustrates our basic problem. OWS was effective in raising the issue of income inequality into popular consciousness, but otherwise was ineffective because it lacked focus, leadership, and intellectual depth. While we need to avoid having our politics be completely dominated by ideology, it is impossible to have a coherent movement without a clear ideological substructure.

There’s much more to be said about this, but if we are going to get anywhere with a new politics, we need to fashion a substantial political movement. To do that, we need to ensure that our movement has the intellectual depth, substance, and coherence to remain vital and motivating.

This series has tried to sketch out what that might look like. But, it’s ultimately pointless to produce a political program without giving any thought to the concrete steps that have to be taken to make it a reality.

Personal Solutions

No lengthy political diatribe would be complete without at least a small dose of sanctimonious self-righteousness. So, in the interest of keeping true to form, please bear with me.

Any movement to get our politics back on track is going to take a personal commitment from each of us to engage with the political process. We can never hope to do what needs to be done unless we all make public service a centerpiece of our personal moralities.

We currently have two principal strategic advantages. First, we have numbers. Without widespread involvement we simply lose that. Second, we have time. Eventually, the political leadership that has gotten us into this mess will pass away and it will be our turn. But that will take decades, and it should be clear that we don’t have that long to wait. If we’re going to save ourselves, we are going to have to start now.

To get that involvement, we are going to have to lose our [hip] cynicism. I have heard far too many of us say things like “the system is fundamentally broken,” or “the government doesn’t care about any of us, so why should I care about it?,” etc. Our disengagement has been driven by our well-founded disgust at the system. But it is self-defeatingly stupid to let that disgust force us to give up on politics.

To those who think that we’re doomed or that we need “Second Amendment solutions” I ask: When was the last time you ran for office? Worked for a campaign? Went to a City Council meeting, testified at a state legislative committee hearing, or wrote a letter to the editor? Do you even know who your legislators are, much less communicate with them as a constituent?

I recognize that that may sound very Sesame Street, but I can tell you from experience that these things actually work. And in any event, it is idiotic to say that the Shining City on a Hill – the great experiment in Freedom, Liberty, and Democracy – is dead and gone without so much as having read a newspaper. Freedom isn’t free, but it costs more than blood and treasure.

The Power of Local Politics

We are certainly right to be skeptical of our ability to jump headlong into national politics. Campaign spending is out of control, and if you’re not a millionaire or have a lot of millionaire friends, you don’t stand a chance at becoming president. But we focus far too much on national politics.

The vast majority of the interactions you have with government on a day-to-day basis are with state and local laws. Virtually every criminal law you try to avoid breaking is state and local. Most of the taxes you run into regularly are state and local sales taxes and surcharges. In fact, most of us only directly interact with the federal government when we file our income taxes.

Moreover, national politics is largely controlled by state politics. State legislatures are responsible for drawing election districts, which has profound consequences for national elections. The Republican Party controls most state legislatures, which explains why Republicans can have more seats in Congress, even when more votes are cast for Democrats.

Whether you think that’s a good thing or bad thing, it’s pretty hard to call it democratic. And all of that is something you can change by participating in state politics.

If we are serious about reshaping American politics, we need not focus on trying to control the presidency or Congress. Instead, we need to focus on local politics. Many state legislative races turn on a few hundred votes, some significantly less. If you can get 100 people to either show up or change their vote, you can often swing an election.

That’s far easier to do than you might think. After just a few election cycles, it’s entirely possible to completely change the course of a state’s laws, and therefore its national trajectory.

The Progressive movement of the early 1900s is an example of how this can work. Virtually every major feature of modern regulatory life has its origins in the Progressive movement. Everything from the FDA to the 40-hour workweek, from the popular election of Senators to traffic lights was the result of the Progressive movement. Yet, in its decades-long history, it won only a small handful of national offices.

Instead, the Progressive movement focused on city councils in major cities and won huge numbers of state legislative offices. They were able to build modern America, one city and state at a time. Before long, national political parties and candidates had to start paying attention, because there was no way for them to get elected without responding to the issues that the Progressive movement had made its centerpiece.

There is no reason to believe that this cannot happen again.

To What End?

The Progressive movement is instructive in terms of what we need to do if we’re going to save our generation’s future. The great gift of the Progressive movement to America was the development of public infrastructure. And if we are going to save ourselves, we are going to have to renew a commitment to the repair and expansion of that infrastructure.

By “infrastructure,” I mean something broader than our crumbling bridges and roads. That physical infrastructure is certainly part of the problem. Our economic success over the past century would not have been possible without our well-developed transportation and energy systems. But neither would it have been possible without a regulatory and legal system that ensured the fair distribution of wealth, and supported people in difficult economic times and old age. Without a world-class public education system, the seeds of American ingenuity would have fallen on barren ground.

In short, infrastructure should be understood as the network of physical, social and regulatory structures that the public creates to make it easier for people to achieve goals consistent with the public good. This notion flows directly from the concept of government as a tool for improving social conditions. Tempered with a conservatively progressive program of developing, rebuilding, and expanding our infrastructure, it can become our generation’s core political project.

I’m reluctant to be much more specific than that because policy questions are complex and require a lot of focused research to find the right solutions to the right problems. But in passing, it’s hard to see a successful political program that doesn’t address the corrosive effects of the Citizens United decision. I think it’s fairly clear that we need massive repair and restructuring of our transportation systems from the city-level up. Lastly, there is a lot of ground to be made up in making public programs and bureaucracies more efficient [as opposed to simply “smaller”]. This includes not only redesigning governmental departments, but also redistributing their resources to make sure that they’re able to do their jobs effectively.

But whatever shape the particular policies would take, what’s important for us is that we be guided by a desire to start taking care of our country again. A well-tended yard and freshly painted front door are signs of someone who cares about their house and has the resources to tend it. In the world’s wealthiest nation, we certainly have the resources. So why are we letting our house go to shambles?

By making public infrastructure that will allow everyone to flourish our political focus, we will be well positioned to start bending the arc of our social decline back in the right direction.

Increased civic involvement is the central feature of “the new infrastructure.” But simply getting more voices into the conversation is not enough. We need people to get engaged, but we also need those people to have a basic understanding of our how political systems work, and to have a basic understanding of how to think through social policy.

Next week’s installment will focus on the policy area in which we can effect the greatest, and most long-lasting improvement in our nation’s future: education.

Fifth In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

Article fouroutlined some tentative first steps towards a set of policies that can respond to the particular problems our generation will face in the coming years. Specifically, it focused on the idea of investing in public infrastructure, understood broadly.

That involved taking the first step of losing our self-defeating cynicism about politics and getting more involved, particularly at the state and local level. But simply having more people involved in the process can’t be all that we’re after. We need people who are willing and able to learn the details of the policy conversation and to understand the processes of change.

For us, this will mean learning these things on our own. But it shouldn’t have to be that way. And it is precisely here that we can see an opportunity for us to make a lasting contribution to our community.

Comprehensive education reform can become the centerpiece of the New Infrastructure. But this reform cannot just be a matter of tinkering around the edges. We need to construct an education reform movement that will strike at the very heart of our education system.

Education For Economic Growth

There is perhaps no idea more universally accepted in American politics than that more and better education is our best hope for addressing social problems. Insofar as many of the defining features of the Bait-and-Switch Generationare economic, education presents itself as theway to fix this mess. That has been the story we’ve been told our entire lives. In fact, I would argue that education sits at the center of the Great Bait-and-Switch: it was the price we were to pay to get the world we were promised.

Our national faith in education is grounded in the well-documented effect that educational attainment has on individual income. A 2014 Pew study found that the median annual earnings of college graduates aged 25–32 were on average $17,500 per yearmore than that of a high school graduate in the same age bracket.

However, we are left with a troubling trend: while educational attainment levelshave grown consistently in recent decades, poverty rateshave barely fluctuated by more than a few percentage points and wealth inequalityhas skyrocketed.

What’s more, rising levels of average education may actually work to increaseeconomic difficulties. As education becomes more accessible and widespread, the cost of notbeing educated increases dramatically.

In 1965, median income [in 2012 dollars] for a college graduate was $38,833 while that for a high school graduate was $31,384 – a difference of $7,449 per year. In 2013, the median income for a high school graduate [in 2012 dollars] had fallen to $28,000, while that for a college graduate had climbed to $45,500. That same year, the poverty rate among Millennials with only a high school education was 22%, while among college graduates it was only 6%.

This has led many of us to seek higher levels of education simply to remain competitive. We are then often forced to take on student loan burdens to meet the ever-increasing costs of a college education. Combined with large-scale wage stagnation, it’s little wonder that students with the lowest levels of educational attainment [and therefore student loan burdens] are those most likely to defaulton their student loan obligations.

To understand why education has this mixed effect, we need to see why increased access to educational resources at the individual level does not translate into access to economic goods at the societal level.

Underlying Structural Factors Are More Important

Over 40 years ago, the philosopher of education Thomas Green theorized that increased education [in our type of education system] was ill-suited to addressing our economic problems. His basic argumentwas this: As a given level of education becomes more widespread, its value as a way to choose between individuals decreases. By the time the last group of people achieves that level of education, it no longer has any economic value. He called this the “group of last entry.”

Because access to wealth almost always means increased access to the highest levels of education, lower socioeconomic groups don’t reach a given level until it has been saturated by the upper and middle classes. The lowest socioeconomic groups are always the group of last entry, and so never get the relative benefits from getting there.

This stems from the basic fact that education, in and of itself, is fundamentally unrelated to economic basics. If everyone in the country got a PhD, it would not eliminate the need for janitors and fry cooks, those jobs would be filled from the same populations that they are now, and they would still be making minimum wage.

There’s nothing wrong with being a janitor or a fry cook. However, this does show that in the presence of other factors, education alonecannot solve our fundamental economic problems. As long as the underlying political factors that have led to our economic woes remain, we shouldn’t expect a more educated and efficient workforce to solve that problem.

But in this last observation we can see a ray of hope for education as a tool for addressing our economic and political problems. Education can be a powerful tool for promoting greater and more sophisticated civic engagement, and thereby bring greater attention and energy to solving our structural problems. However, we are mistaken if we expect business-as-usual education to do the work for us. Instead, we are going to have to fundamentally rethink why we educate.

The Root Of The Problem

That education is the route to solving all of our problems is plausible precisely because education touches the basic foundations of everything that we do in society. Our education teaches us how to think, how to behave, what attitudes are appropriate, etc. It is the principal organ through which our society reproduces itself.

However, because we view everything through the lens of economic productivity, education’s power to address our social problems has been significantly hindered. For the past 30 years we have been obsessively focused on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics [STEM] education. As a result, all of our effort, money, and resources are directed away from other parts of the curriculum. We end up producing people steeped in the workings of the universe, but with little to no understanding of the workings of public life; people who know how to operate business technology, but not the technologies of our democracy.

Our generation’s entire educational experience has been wrapped in the push for STEM supremacy while neglecting virtually every other sphere of education. And throughout, we have been subjected to one of the largest and most profoundly failed experiments in education history: No Child Left Behind and it’s progeny [Race to the Top, high-stakes testing, etc.]. It’s frankly a miracle we’re as politically active and engaged as we are, and speaks volumes to the courage and skill of our teachers.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In [re]building our education system, we have to return to the question of what kinds of people we want to produce. That can sound scary, but it means nothing more than this: do we want to produce people who are effective and qualified workers and business leaders, or do we want to produce people who are effective and qualified citizens? Importantly we have to reject the century-old habit of policy thinking that those two are necessarily the same.

Here again, I am reluctant to be much more specific because education policy is extraordinarily complicated. But at a minimum, there a few things that plainly have to change.

First, refocusing our educational mission on developing citizenship entails a rebalancing of the curriculum. Not only would we have to place greater emphasis on social studies, but we would have to severely rethink what we teach as a part of that curriculum. Many of us share the experience of graduating high school being able to name Revolutionary War battles and Civil War generals, but without even a basic knowledge of how laws get made [beyond what we learned from Schoolhouse Rock], or of how to process basic social science statistics.

Secondly, it would require us to stop being so worried that our children might form an opinion at school. As it is, our education is so sanitized of controversy that it can’t connect to issues directly relevant to students’ lives. We can make schools a forum where students can engage in the life of the community and develop a robust sense that, as citizens, they have the right, the power, and the obligation to inform how that community develops.

Wherever we end up on curriculum, the most vital and fundamental shift we have to make is to return teachers to their appropriate place in this conversation. Even in the depth of our current educational dysfunction, teachers perform one of the most profoundly important jobs in our society. The teaching profession is the bedrock of our status as a free society, and the way that we treat teachers – low pay, public scorn, perpetual interference, etc. – is a disgrace.

But even more stupefying, we hardly pay any attention to them when we talk about education reform. Education is the only sphere of public life where we feel entitled to speak as experts by virtue of having gone through the system once. Policymakers without any training or experience as educators design reforms with little more than pro forma consultation with educators. It’s rather like a car company CEO deciding to design a car without speaking with any mechanical engineers or auto mechanics. With something as profoundly important as education, this is as dangerous as it is stupid.

Because education forms the habits of mind and action that shape who we are as people, it touches every aspect of our lives. Committing ourselves to fundamental education reform calls us to rethink our fundamental aspirations as a society, and to focus our attention on the institution that should rightly occupy the center of public life. To the extent that we can construct an education policy that is explicitly focused on improving our capacity as democratic citizens, we can permanently alter the trajectory of American politics for the better.

The solutions to our generational crisis are there, and they’re within our reach. But all of this is will come to naught if we don’t take action and soon.

Next week’s article, the last in the series, will take a step back to look again at the big picture and to make the case for why weneed to act and why we need to do it now.

Last In A Series

BY CHRISTIAAN MITCHELL

If this series can be summarized in a sentence, it is this: ideology driven politics is destroying American government at exactly the moment when we Millennials need it to function most, and we need to act now to stop it.

While the focus of the series has mostly been on this as a national problem, the catastrophic consequences of governing through ideology rather than policy are dramatically illustrated right here at home in Oklahoma.

We are No. 1 in per capita police use of force, No. 1 in the incarceration of women, in the bottom third of the nation in poverty[one quarter of our children don’t have enough to eat], our roads and bridges are crumbling, and the state government is facing a nearly $1 billion– one-seventh of our entire budget– shortfall.

The state is killing our men, and incarcerating our women. Our children are starving, our roads disintegrating, and our government is flirting with collapse. The very ground has started to quake in revoltagainst our economy.

And what are our leaders doing to address these problems? They’re calling for an amendment to the state constitutionso they can put the Ten Commandments back at the statehouse. They’re squandering taxpayer dollars on borderline frivolous lawsuits against the federal government, because of “Obama.” They’re slashing taxesand trying to figure out ways to sell off our landand water.

We’ve seen this before. The farm is deep in hock and not producing enough to get it out. Our only option left is to sell. The problem is, there ain’t no peach pickin’ job for the state of Oklahoma out in Californie.

Even if there were, we’re so sold on the discredited ideologyof cutting your way to prosperity that we’d probably just quit the job anyway, because apparently the way to increase revenues is to get rid of revenue sources.

If you’re not angry about this, you’re not paying attention.

Millennial Tools

But despite the pessimism it’s easy to feel about where we’re headed, there’s hope. We have a historically unprecedented ability to organize and share information.

It’s become a cliché to talk about how the advent of the Internet has changed the world. However, it’s also far too easy for us to overlook the fact that we are in the midst of an epochal shift. Because most of us Millennials have grown up steeped in the digital era, we have little appreciation for what a profound time that we live in.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, these are the new tools of social organization and communication. And they allow us to connect with one another, to share ideas, and to mobilize the public in profound new ways. If you doubt their power, ask Hosni Mubarakhow quickly Facebook can destroy a decades-old regime.

We may not be quite to that point yet, but we really can’t afford not to appreciate the historic power at our fingertips. The Revolution is not going to be televised because no one watches TV anymore.

Millennial Power

As I noted beforethe Occupy Movement appreciated the power of these new tools, but lacked the focus and depth to be able to convert their mass movement into mass political power.

If we are going to put ourselves back on the right track, we have to appreciate the difference between organizing and mobilizingpublic opinion. Without an organized, focused, and disciplined political movement, any hope we have of inserting a measure of sanity back into our local and national politics is just that, a hope.

I don’t know what that political organization looks like for us. It could simply mean running for office and turning out in greater numbers for candidates who share our desire for less nonsense in politics. At the other end of the spectrum, it could mean the formation of a new political party dedicated to gaining power so that it can broker Millennial solutions to our political problems. But whatever it is, it has to be ours and it has to stay focused on being the adults in the room.

The Millennial Revolution

Many people are skeptical of this “people power” stuff. In fact, I’m convinced that, among people who aren’t fundamentally confused about what the word “socialism” means, whether you support Bernie Sanders comes down to whether you believe that an organized public can effect real political change. And at this point, more people seem to doubt that than not.

But without taking a position on the Democratic primary, I would submit that this nation is built upon the idea that we have the right and obligation to shape our governance.

While many of us are rightly cool on the idea of American Exceptionalism, we are the inheritors of one of the great political movements of the Rational Enlightenment. And for all of the flaws that come with that, there is one great gift that is written into the subtext of our founding documents: enlightenment is an ongoing process.

Politically speaking, that means that we have to be willing to look at what we’re doing and be willing to criticize it. But if that is ever going to rise above the level of mere whining, we also have to be willing to act.

We simply cannot afford to “wait our turn” for political leadership. Another 10, 20, or 30 years of ideological, Baby Boomer-dominated politics will destroy any hope we have of building a better future for ourselves and our children.