BY KEN NEAL

Changing the names of Fort Hood and Fort Benning named after generals initially seemed a bit excessive, but then I made a quick study of the generals for whom they are named and the dates when the forts were named.

Changing the names of Fort Hood and Fort Benning named after generals initially seemed a bit excessive, but then I made a quick study of the generals for whom they are named and the dates when the forts were named.

What I learned in my shallow dive into history changed my mind.

Fort Hood was officially opened Sept. 18, 1942 when the country mobilized after Pearl Harbor. It was named for the Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood, who commanded Hood’s Texas Brigade during the civil war. Hood was one of the youngest generals on either side. He lost an arm at Gettysburg and a leg at Chickamauga, but still commanded the army of Tennessee in the later part of the war. He was obviously an outstanding soldier and it seemed fitting that Texas would have a fort named after him.

Fort Benning is named after Henry L. Benning, also a general in the Confederate army during the Civil war. Benning was an ardent pro-slavery politician before leading troops in the war. He was a United States senator from Mississippi before the war. First opened in 1909 as camp, the post was renamed to Fort Benning in 1922.

Both are in Confederate states and were named for the generals during the height of Jim Crow days.

Recent events that have made all of us aware of racism has awakened a call to rename the forts, a move that President Trump, of course, opposes. Congress has signaled its willingness to change the names. But why change them?

The short answer is because Hood and Benning were generals who were a part of the effort to break up the nation via civil war. The best reason, though, is because they are more emblems of the determination of the old South to reinstitute slavery than commemoration of the war.

Lincoln treated the Civil War as a rebellion that had to be put down to save the Union. After the war, he welcomed these rebel generals as U.S. citizens, provided they pledged allegiance. It was the right thing. He could have tried the southern leaders, certainly from Jefferson and the Confederate officer corps as war criminals. Indeed, many northerners wanted them hanged.

Lincoln’s generous treatment of the South failed. By 1876, Republican Rutherford Hayes fell one electoral vote short of election. He was named president by the House when southern Democrats agreed to elect him provided the hated federal troops were removed from the South. His opponent, Samuel Tilden, won the popular vote.

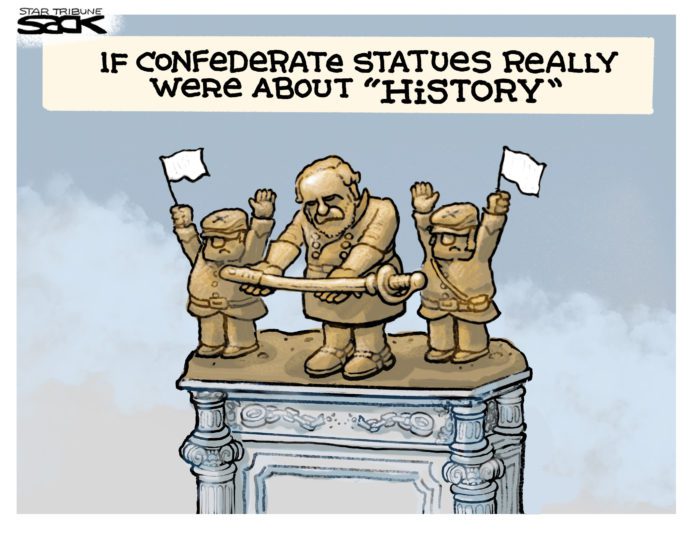

That bargain allowed the South to go full speed putting laws on state books that effectively enslaved blacks once again. Most of the monuments to Confederate generals came during Jim Crow days as Southerners tried to restore their “way of life.”

The South’s “gallant” fight to keep a culture dependent on slavery has been so romanticized through the years that it seems at first unreasonable to take the names off forts and take down monuments to the war.

But it’s not. These generals and others were indeed traitors forgiven by Abraham Lincoln in hopes of healing the country. Southerners took advantage of him to resurrect white supremacy.

In the language of Lincoln, it is altogether fitting that the forts be renamed.

– Ken Neal is former opinion editor of the Tulsa World