BY GENE POLICINSKI

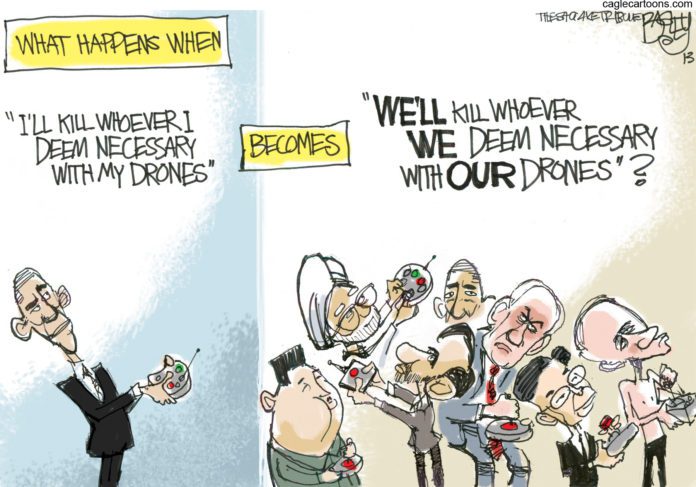

Much attention has been focused in recent days on the Obama Administration’s semi-secret “drone” program and on reports of covert surveillance and lethal attacks on terrorist targets in the Middle East and elsewhere.

The use of such deadly force through the use of remotely piloted aircraft by the U.S. military certainly deserves scrutiny – as does the news media’s role in keeping citizens up to date on such overseas programs, secret or not.

But First Amendment and related privacy issues back home in the United States also are raised by the rapid growth and future use of the use of such drones by local government authorities, regulatory agencies or even our fellow citizens.

The Associated Press, New York Times and the Washington Post are all reported to have agreed at differing times since 2011 to withhold the location of a secret drone base established in Saudi Arabia. An Associated Press spokesman said that the wire service agreed to keep silent after U.S. officials make a case that revealing the location would make the base a target of extremists, endangering U.S. personnel directly, and would endanger counter-terror efforts.

AP has noted that it did report on “secret drone operations operating from the region.” And there are reports that in 2011, FoxNews.com and the Times of London both reported the creation of U.S. bases in the Horn of Africa region, and in Saudi Arabia.

Some press critics and those opposed to lethal drone strikes have criticized the decisions not to publish the base information as soon as it was known and confirmed. But others have responded with a blunt axiom that has guided such decisions for many journalists through the years: Do you want to risk causing the death of even one American by printing what you know?

There are no easy answers to balancing this concern with the role of a free press as a “watchdog on government.”

But beyond that conundrum are a host of other constitutional issues by the rapidly developing technology of drones and pilotless aircraft – some the size of small airliners and others literally as small as a hummingbird – that as citizens we need [pardon the expression] “to keep an eye on.”

Even as the “unmanned vehicle systems” industry gather for a conference in suburban Washington, DC, federal lawmakers and a variety of states – including Oklahoma – are considering legislation to regulate where, when and how much such devices are allowed to gather, record and report.

Potential uses by local police and fire departments include the use of drone aircraft in hostage rescue or lost-child searches, to replace expensive piloted helicopters in daily duty such as traffic and accident reporting, and to track forest fires without endangering human crews. And beyond law enforcement, drones are being touted as easy, inexpensive devices for everything from surveying remote locations to keeping track of crop growth or the spread of agricultural diseases.

But balancing the benefits are concerns ranging from high-tech “peeping Toms” to threats to Constitutional rights.

“Our founders had no conception of things that would fly over them at night and peer into their backyards and send signals back to a home base,” said state Sen. Donald McEachin, D-VA, and a sponsor of a bill setting out a two-year moratorium on police and official agency drone use in the state, according to report by Fox News.

Legislation requiring court-issued search warrants in the police use of drones has been introduced in states including Montana, Maine, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, Florida, Oregon and California, according to various news reports.

It isn’t science fiction any longer to consider the Orwellian impact on public demonstrations where a government “eye-in-the-sky” linked to facial-recognition software now used in land-based cameras could enable police to identify each person in a march or picket line – and perhaps in the process also “tag” bystanders or journalists. And what should we make of private companies or private investigators someday using airborne devices to monitor workers or to gather evidence on errant spouses?

Privacy concerns about new technology have been around since long before drones entered the headlines. In 1890, future U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis co-authored a law journal article on the “right to be let alone” in the face of new inventions of the era: photography and mass circulation newspapers.

Brandeis and colleague Samuel Warren warned more than 120 years ago that “numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that “what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.”

We can only wonder what they would have made of a small camera-and-radio equipped device hovering over those very same rooftops.

– Gene Policinski is senior vice president and executive director of the First Amendment Center in Nashville, TN