BY DAVID PERRYMAN

On Dec. 16, 1773, 116 men, several of whom were dressed as members of the Mohawk tribe, threw 342 chests full of tea into Boston Harbor.

On Dec. 16, 1773, 116 men, several of whom were dressed as members of the Mohawk tribe, threw 342 chests full of tea into Boston Harbor.

The rest of the story involves tax credits, government bailouts, monopolies, American ships and, yes, even tort reform in 2013.

It is natural to think that the Boston Tea Party, as it has become known, was a reaction to high taxes imposed by the British Parliament.

However, to understand the issues that precipitated the event that for decades was simply known as “the destruction of the tea” we have to go back to Dec. 31, 1600, when the British Crown chartered and granted favored status to a business known as “The Governor and Company of Merchants of London, trading with the East Indies” for the importation of agricultural goods and products from the area of India and the Middle East.

In time, the mega-corporation that had its own military, counted opium among its commodities and for several decades was the world’s largest drug-dealing operation became known as simply, “The East India Company,” or the “EIC.” Many members of parliament owned interests in the EIC and, eerily like 21st Century politics, the company’s paid lobbyists were always available to “help” make laws.

Through favorable legislation, government incentives and protectionist policies, the EIC reaped huge profits and lined the pockets of England’s merchants and members of parliament. Enter the American colonies.

The EIC eyed the emerging American market; however, 85% of the tea drank in America was smuggled Dutch tea. In 1767, lobbyists for the East India Company compelled parliament to grant it a tax credit rebating to the company a chunk of the tax on tea that was re-exported to the colonies so that it could compete with the smuggled tea.

In 1772, the tax rebate expired. Sales plummeted, warehouses were full of unwanted tea and the EIC, perhaps England’s most profitable commercial entity was in dire financial trouble. May 1773 dealt a blow to free enterprise when the lobbyists of the East India Company convinced parliament to enact the “Tea Act,” restoring the tax credit and allowing the company to bypass colonial businessmen who had previously bought and sold tea. In July 1773, the East India Company selected agents in the colonies who would simply be hired to sell tea on commission.

What transpired aboard the Dartmouth, the Eleanor and the Beaver – three American ships carrying East India Company tea into Boston Harbor – was not at all about high taxes. As a result of the Tea Act, East India Company tea was now cheaper than smuggled Dutch tea.

The destruction of the tea was as much of a protest against a large commercial conglomerate that had used its financial and political influence to create a government sanctioned monopoly as it was about a lack of representation.

The benchmark of the United States is its system of private capitalism. Theoretically, and as it should be, it is a system under which, without asking anybody’s permission, various enterprises compete with each other in the market by offering the highest quality goods and services they can, at the lowest possible prices. Progress occurs as companies and individuals strive continuously to raise quality and lower their prices.

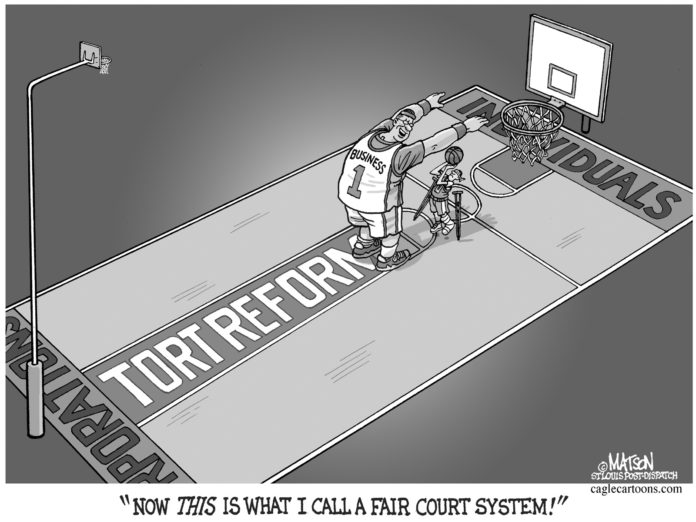

In September, the Legislature will return to Oklahoma City. The special session has been called to review several statutes that were adopted in 2009 and ruled unconstitutional earlier this year.

Among other things, those statutes limit the amount of money an injured person or the family of a deceased person may receive from the person or company who caused the damage, injury or death; make it more expensive to sue a company or another person who has caused injury or death; and make it more difficult to hold someone accountable if they harm a person, such as a nursing home resident or a child.

Our Founding Fathers drafted the constitutions of the United States and the state of Oklahoma to give ordinary citizens the right to hold accountable those who violate the rules of society and cause harm to others. We must carefully examine whether the legislation that will be introduced this session will be in the common good.

The last thing we should do is allow the rights of the people to govern themselves through trial by jury to be taken away or infringed.

On the day after the Destruction of the Tea, John Adams, who would later become our nation’s second president, wrote in his diary, “Last Night three cargoes of tea were emptied into the sea. This morning a Man of War sails. This is the most magnificent movement of all. There is a Dignity, a Majesty, a Sublimity, in this last effort of the Patriots, that I greatly admire. The People should never rise, without doing something to be remembered – something notable and striking. This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important consequences, and so lasting, that I can’t but consider it as an epoch in history.”

Contrary to the Common Good, the East India Company sought government protection before America’s independence. Will the Common Good be served in this century by those corporations and their lobbyists who want government to step in and artificially tilt the scales of justice in their direction?

– David Perryman, a Chickasha Democrat, represents District 56 in the Oklahoma House of Representatives