BY RALPH NADER

Thanksgiving is a time for family, food and joy, but unfortunately it can also be a source of health-impacting stress and anxiety for many.

Thanksgiving is a time for family, food and joy, but unfortunately it can also be a source of health-impacting stress and anxiety for many.

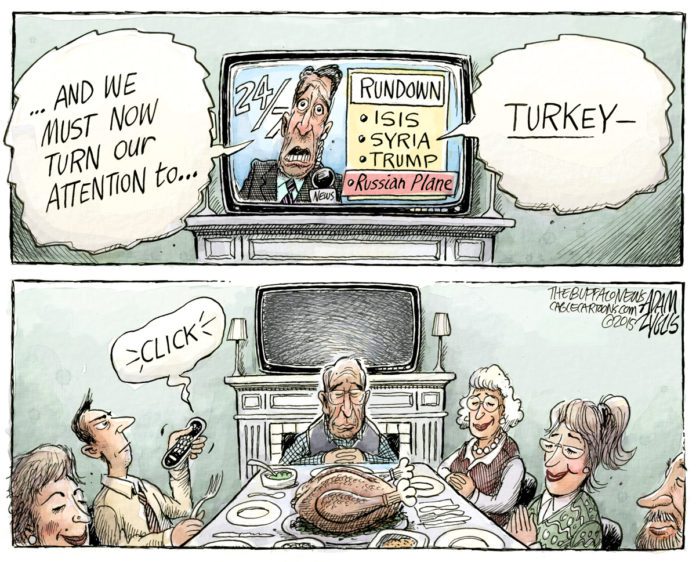

Between the influx of visitors, football games on the television and the necessary shopping, cooking and cleaning up, there can be far too little time devoted to reflective conversation with friends and family.

And once the feast is finished and the guests have left, there is precious little time for quiet contemplation when all forms of mass media are rabidly encouraging Americans to participate in the obscene corporate-driven “Black Friday” and “Cyber Monday” sales craze.

Go go go! Buy buy buy!

Perhaps we should be taking a different approach to the holidays.

In my book, The Seventeen Traditions about the wisdom my parents passed along to my siblings and me, I wrote a chapter about “the tradition of solitude.”

Here’s a relevant excerpt for the season:

Some years ago, we invited a family with two small children over for Thanksgiving dinner. The four-year-old boy spent the whole day running wild, jumping off the table, knocking over glasses of water, screeching at the top of his lungs, and generally making every effort possible to ruin the conversation and the meal. Today, most parents might ask: Was he suffering from attention deficit disorder? No, the parents were suffering – from an unwillingness to control their son’s behavior and lay down some markers. It’s a symptom of today’s sprawled economy that many children spend less time with adults, including their parents, than any previous generation in history. When they do have a few precious moments with adults, they often act out as if they’re desperately trying to make up for prolonged inattention.

Does any of this sound familiar? I expect many millions of Americans will be dealing with similar household chaos on Thanksgiving Day.

My mother believed that children should be able to exercise their minds, to think independently and be self-reliant. Critical to this development is acknowledging the importance of solitude. Devoting time to oneself and one’s thoughts isn’t just important for developing youngsters, however. Many grown adults could benefit from a little “quiet space” to get to know themselves and the world better.

The tradition of solitude isn’t about sitting in a room and contemplating one’s navel. It’s about allowing one’s mind to rejuvenate, imagine and explore – and hopefully relieve itself from the stress and anxiety that inevitably come with the burdens of everyday life. It’s an engine of renewal. This is particularly true around the holidays when expectations and obligations can mount.

Another excerpt:

True solitude can involve an infinite variety of experience: being alone with one’s imagination, one’s thoughts, dreams, one’s puzzles and books, one’s knitting or hobbies, from carving wood blocks, to building little radios or model airplanes or collecting colorful stamps from all over the world. Being alone can mean following the flight of a butterfly or a hummingbird or an industrious pollinating bee. It can mean gazing at the nighttime sky, full of those familiar constellations, and trying to identify them.

I recently filmed a video in my hometown of Winsted, CT where I discussed my relationship with nature and the comforting solitude it provides. Watch it here. The holiday season seems like an appropriate time to share this video in the hopes that it inspires others to reflect on the quiet, memorable moments and places that matter most.

Consider turning off the television, putting away the smartphone, avoiding the marketplace invitations to shop and spend on “Black Friday” and seeking comfort in solitude.

Perhaps the joys of solitude can become a tradition that eclipses the crazy call to spend the day after Thanksgiving shopping instead of thinking.

I welcome others to share the quiet places where they experience the joys of solitude. Maybe by telling others about how we retreat to find our better humanity, we can encourage those among us still searching for this intrinsic solace.

Nader.org