BY JOHN THOMPSON

The New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof is the latest supporter of school reform to acknowledge that the market-driven movement has peaked. He then cites Oklahoma when calling for a new science-based approach to school improvement.

The New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof is the latest supporter of school reform to acknowledge that the market-driven movement has peaked. He then cites Oklahoma when calling for a new science-based approach to school improvement.

The entire nation should listen to Kristof’s wisdom. We in Oklahoma City, especially, should think about what we could accomplish by ending our bitter education civil war and focusing on high-quality early education.

Kristof describes competition-driven school improvement as an idealistic movement where “armies of college graduates joined Teach for America. Zillionaires invested in charter schools. Liberals and conservatives, holding their noses and agreeing on nothing else, cooperated to proclaim education the civil rights issue of our time.”

But now, these reform “brawls have left everyone battered and bloodied, from reformers to teachers unions.” Kristof observes that “the zillionaires are bruised. The idealists are dispirited. … The Common Core curriculum is now an orphan, with politicians vigorously denying paternity.” Those expensive campaigns have left K-12 education “an exhausted, bloodsoaked battlefield. It’s Agincourt, the day after.”

Kristof provides three reasons why we should “refocus some reformist passions on early childhood.” He starts with the scientific evidence that “early childhood is a crucial period when the brain is most malleable, when interventions are most cost-effective for at-risk kids.”

The internationally renowned journalist knows from experience that “helping teenagers and adults is tough when they’ve dropped out of school, had babies, joined gangs, compiled arrest records or self-medicated.”

But he has seen the benefits of high-quality early education in Oklahoma where:

I once met two little girls, ages three and four, whose great-grandmother had her first child at 13, whose grandmother had her first at 15, whose mom had her first at 13 and now has four children by three fathers. These two little girls will break that cycle, I’m betting, because they [along with the relative caring for them] are getting help from an outstanding early childhood program called Educare. Those two little girls have a shot at opportunity.

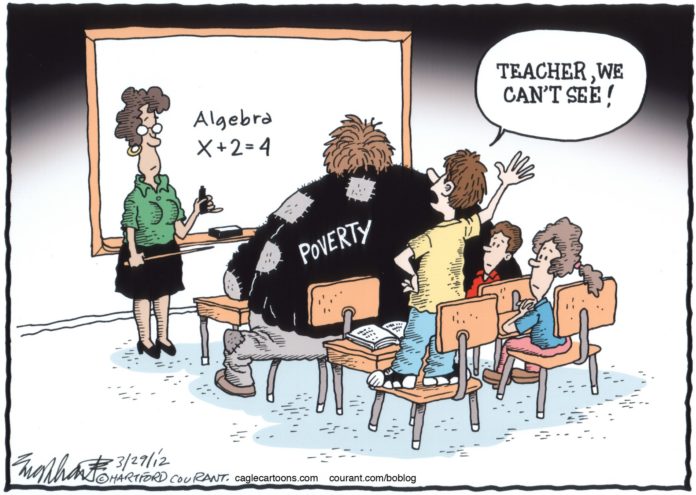

Kristof could have also had Oklahoma City in mind when he explained the second reason why it is time to find a new school reform approach. He notes that reformers picked “the low-hanging fruit” of the K-12 world. While we should applaud the successes of the best charters, the fact remains that they accept only as many of the highest-challenge students as they can handle. This means that OKCPS neighborhood schools are left with even more intense concentrations of generational poverty. The unintended result is that our traditional public schools are overwhelmed by unmanageable numbers of children who have endured extreme trauma.

Third, Kristof cites Oklahoma as evidence that early education is the most politically viable option. He notes, “New York City liberals have embraced preschool, but so have Oklahoma conservatives. Teacher unions will flinch at some of what I say, but they have been great advocates for early education. Congress can’t agree on much, but Republicans and Democrats just approved new funding for home visitation for low-income toddlers.”

Kristof does not criticize so-called “corporate reformers,” or the Obama Administration for imposing the entire test-driven school improvement package on every classroom in the diverse nation.

In order to persuade Oklahoma City to refocus, however, it is probably necessary to explain why [to take just one example] the tens of millions of federal School Improvement Grants [SIG] dollars have failed to improve our schools. Otherwise, patrons might buy into the latest national reform gamble and try to “blow up” the system in order to save it.

[OKC had one SIG success, but as with most of the country, most SIG schools failed to improve; nationally, one-third of SIG schools produced declines in student performance.]

The SIG was supposed to be based on the Gates-funded The Turnaround Challenge. It explained why it is impossible to turnaround the most challenging schools – like the OKCPS schools that received $5 million SIG grants – without first creating the types of socio-emotional supports that are provided by Educare and the best early childhood programs. SIG rules required schools to rush ahead without laying that foundation.

Oklahoma City was as professional as other districts in following the game plan imposed by the federal government. We did our best to build a skyscraper on sand.

The billions of dollars wasted on the SIG, the RttT, VAMs, and the rest of the alphabet soup of test-driven school reform are gone. We are back to trying to hold our traditional public schools together with the meager $8,000 per student that is appropriated in our state.

But, like Nick Kristof, we can learn lessons from those failed experiments. We should first ask what we could have accomplished if tens of millions of these federal dollars had been invested in Educare. We should then pull together, leverage our local resources and national grant money in order to start anew – this time concentrating on whatever it takes to provide high quality early education.

The bad news is that a huge body of research explains why No Child Left Behind and the test, sort, and punish policies of the last dozen years were doomed in terms of improving Oklahoma City secondary schools that serve the census tracts characterized as having “extreme poverty.”

The good news is that we only have 13 of those tracts. With the money wasted on the SIG, we could have scaled up Educare to the point where all of our highest-poverty neighborhoods were provided the best possible science-based interventions.

It also would have been the single most effective policy for promoting Oklahoma City as a place for business investment and to raise families.

There is no point in crying over the spilled dollars that went into K-12 reforms. Neither is there a point to rehashing the many reasons why the battle between top-down test-driven reformers and educators became so bitter. Patrons have seen the damage done by test-driven reward and punishment policies.

And we have a choice in Oklahoma City and the rest of the nation. We can continue to starve our schools and to fund ever-more-expensive political battles, or we could pull together in a public-private partnership.

As Oklahoma competes in the global marketplace, we have a choice. Do we want to continue to read about ourselves as the national press covers our violence, racial and social conflict, and our political squabbles? Or do we want the type of publicity that would come from pulling together and fully investing in Educare and the other proven policies cited in Kristof’s influential commentary?

– Dr. John Thompson, an education writer whose essays appear regularly in The Oklahoma Observer and at the Huffington Post, currently is working on a book about his experiences teaching for two decades in the inner city of OKC. He has a doctorate from Rutgers University and is the author of Closing the Frontier: Radical Responses in Oklahoma Politics.