BY RICHARD L. FRICKER

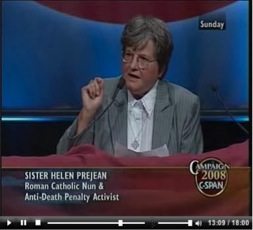

In 1957, 18-year-old Louisiana native Helen Prejean joined the Sisters of St. Joseph Medaille. She was embarking on a journey that has taken her around the world. She has been bestowed with honors from hundreds of universities, societies and legislatures, both in the United States and other countries.

In 1957, 18-year-old Louisiana native Helen Prejean joined the Sisters of St. Joseph Medaille. She was embarking on a journey that has taken her around the world. She has been bestowed with honors from hundreds of universities, societies and legislatures, both in the United States and other countries.

By 1981 the now 42-year-old Sister Helen had spent her career working with the poor of New Orleans. Then her journey, which is how she refers to her ministry, took an unexpected turn that would eventually impact the nation and individuals in ways never expected.

Sr. Helen became the spiritual minister to Patrick Sonnier a death row inmate at Louisiana’s Angola prison. Her work with Sonnier, and eventually other prisoners awaiting execution, inspired her to write 1993 Pulitzer Prize nominated Dead Man Walking.

Dead Man Walking stayed on the New York Times best-seller list for 31 weeks. It has been translated into several languages and serves as a landmark condemnation of the death penalty in America.

Sr. Helen’s book fanned the death penalty debate in the same way John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me peeled away southern racism’s veneer of gentility.

The book became a movie in 1996. Produced by Tim Robbins with Sean Penn as Sonnier it provided a though-provoking look at an institution other western countries, in fact half the members of the United Nations, have long since abandoned.

The opera Dead Man Walking opened in San Francisco in 2000. It has traveled around the country and is now set to open in Tulsa Feb. 25 and for two weekends following.

The music was composed by Jake Heggie with the libretto by Terrance McNally. Sr. Helen and Tulsa Opera Artistic Director Kostis Protopapas also describe the work as a journey.

Sr. Helen will speak at the University of Tulsa at the Lorton Performing Arts Center on Tuesday. As a prelude to her appearance and the opening of the opera, she spoke with The Observer about her work and the opera.

Sr. Helen is busy. “I’m busy as a loon. I stay on the road giving interviews. I have a good life. I do keep accompanying people on death row.”

She has witnessed five executions at Angola prison.

Asked what progress has been made over the years, she said, “You can see it happening around the country. The death penalty is in diminishment.”

“It started with Gov. George Ryan of Illinois when it was learned there were thirteen innocent people of death row. Ryan began making his own journey when the stateLlegislature wouldn’t reform the process.”

One of his last acts as governor in 2003 was to commute all one hundred and sixty death sentences to life. There were some efforts to overturn his executive order, but they failed.

For his own part Ryan was later convicted of bribery and other federal charges. He was sentenced to six and a half years in federal prison in 2006. He is, however, considered to be the man who single-handedly reformed the state criminal justice system.

Referring to Ryan again she said, “When he did that the number of death sentences began to be cut in half. Prosecutors were not asking for death as much and juries seemed to not be giving the death penalty as often.”

“The public will for executions seems to have weakened. Last year was the lowest number of executions since the death penalty was reinstated.”

Among other things, Sr. Helen cites the reason for the reduction is the cost of execution. She cites a 2011 study by California Senior Judge Arthur Alarcon and Loyola Law School professor which say executions in California have cost an average $308 million since 1978. The study also says it’s costing roughly $178 million a year to maintain their current death row system.

A life without parole policy would cost the state about $11.5 million compared to the current costs.

Oklahoma currently has 88 inmates awaiting execution. A cost estimate for Oklahoma’s remains unreported.

So if states that are strapped for cash continue a policy that seems to only cost more each year, what is the engine that drives capital punishment?

“Politics!” she says emphatically, “It’s not really about crime at all. What I’ve come to understand is that it’s driven by politics.”

“It’s the easiest thing in the world for someone running for office to be in favor of the death penalty, to show they’re tough on crime. That also saves them from having to get at the root causes of crime and violence. Just hold the symbolism up.”

“Prosecutors are very selective about when they ask for the death penalty. The prosecutor who is running for office will show that they’re tough on crime when they get a sensational case and the media picks up on it, they go for the death penalty and get a notch on their belt. It has nothing to do with fighting crime.”

“When people are thinking politically they like the death penalty. You have to talk to politicians in a way that shows they can have faith awareness and still have justice. And that does not mean killing other people. When you talk to politicians you have to say this is not what Jesus told us to do, he did not tell us to kill our enemies.”

People want, and have the right, to be safe she says. When people understand the Life Without Parole will keep them safe, they no longer support the death penalty.

“Pro-life,” responding to why so many conservatives are against abortion but favor the death penalty, “means not just protecting the innocent, it means all life, not killing people.”

Art is one of the important means to educating people about the death penalty according to Sr. Helen. The Dead Man Walking opera is a part of the education process.

The opera opens with the crime; a young couple brutally murdered, and then follows Sr. Helen and the convicted inmate to the execution. “I’m on a journey and you’re coming with me.”

“You see the crime, you know who did it, they’re not remorseful and justice demands their death. Then the journey begins.”

“All this is played out in music. The victims sing and cry about their pain. You meet the mother of the man to be executed and you see her pain. Then you see her saying goodbye to her son.”

She notes, after an execution the death is listed on the death certificate as a homicide.

“Art raises the reflection, it not always provides an answer but creates the question,” she said.

“We have to help people make the journey. What we do is to bring people into both sides of their heart and deeper reflection.”

– Richard L. Fricker lives in Tulsa, OK and is a regular contributor to The Oklahoma Observer. His latest book, Martian Llama Racing Explained, is available at http://www.richardfricker.com.